Vietnam People: Culture, History, Ethnic Groups and Life Today

Vietnam people live in a country where ancient traditions meet rapid economic growth and digital change. From crowded deltas and megacities to quiet upland villages, everyday life reflects a long history, rich cultural diversity and strong family ties. Understanding Vietnam country and people is important for anyone who wants to travel, study, work or build partnerships there. This article introduces who the people in Vietnam are, how their society developed, and how they are living and changing today.

Introduction to Vietnam People and Their Diverse Society

Vietnam Country and People at a Glance

The country has a population of a little over 100 million people, making it one of the most populous nations in the region. Most Vietnam people live in lowland areas such as the Red River Delta in the north and the Mekong Delta in the south, while large cities like Hà Nội and Ho Chi Minh City act as political and economic hubs.

The social structure of Vietnam combines rural farming communities, industrial workers, service employees and a growing middle class engaged in education, technology and small business. While the majority group is the Kinh, there are dozens of officially recognized ethnic minorities, each with distinct languages and customs. Learning about Vietnam country and people helps travelers navigate social norms, supports students who want to understand regional history, and assists professionals cooperating with Vietnamese partners or relocating for work.

Across the country, people in Vietnam negotiate a balance between continuity and change. Traditional values such as respect for elders, community cooperation and ancestral remembrance remain strong. At the same time, mobile phones, social media, international trade and migration are reshaping daily routines and ambitions. This article explores key themes that define Vietnam people today: their demographic profile, ethnic diversity, historical experiences, religious life, family values, diaspora communities and the impact of modernization.

How Vietnam’s Past and Present Shape Its People

The identity of Vietnam people has been formed by centuries of interaction with powerful neighbors, colonial powers and global markets. Vietnam’s history includes early kingdoms in the Red River region, long periods of Chinese rule, struggles for independence, French colonialism and a major 20th‑century war. These experiences produced strong ideas about defending the homeland, valuing education and honoring those who sacrificed for the community. They also left varied memories and interpretations across regions and generations.

In the late 20th century, economic reforms and opening to the world transformed daily life. Market‑oriented policies, often called “Đổi Mới,” encouraged private enterprise and foreign investment, lifting many households out of poverty. Young people in big cities work in factories, offices, cafés and digital companies, while rural families continue rice cultivation, aquaculture and small‑scale trade. The contrast between tradition and modernization appears in clothing choices, marriage patterns, media consumption and migration from countryside to city.

At the same time, diversity of experience is important to recognize. An urban professional in Đà Nẵng, a fisher in Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu, a Hmong farmer in Hà Giang and a Vietnamese student in Germany may all describe “Vietnamese identity” differently. The sections that follow look more closely at demographics, ethnic groups, religion, family life and the Vietnamese diaspora, while keeping in mind that Vietnam people are not a single uniform group but a varied society linked by shared history and language.

Who Are the People of Vietnam?

Quick Facts About Vietnam’s Population

It is useful to begin with a few simple facts about the people in Vietnam today. The figures below are rounded, approximate values designed to be easy to remember. They may change over time as new data becomes available, but they give a clear snapshot of Vietnam country and people in the early 21st century.

| Indicator | Approximate Value |

|---|---|

| Total population | Just over 100 million people |

| Global population rank | Around 15th–20th largest |

| Life expectancy at birth | Mid‑70s (years) |

| Adult literacy rate | Above 90% |

| Urban population share | About 35–40% |

| Number of recognized ethnic groups | 54 (including the Kinh majority) |

These indicators suggest that Vietnam has moved from a low‑income agrarian society toward a more urban, educated country with rising living standards. Longer life expectancy reflects better nutrition, expanded vaccination and improved health services, though gaps remain between regions. High literacy and widespread basic education show how strongly Vietnam people value schooling and how much effort the state and families invest in children’s learning.

The relatively moderate level of urbanization means that rural life and agriculture still matter greatly, even though major cities are expanding quickly. The existence of dozens of ethnic groups indicates that “Vietnam people” include many communities with their own histories and identities. When reading demographic statements, it is helpful to remember that averages can hide local differences in income, health or educational opportunity between city and countryside, or between the Kinh and some minority groups.

What Are Vietnamese People Known For?

International visitors often describe Vietnam people as friendly, resilient and family‑oriented. Hospitality is a visible feature of daily life: guests are frequently offered tea, fruit or a small meal, even in modest homes. Respectful behavior, especially toward elders, is expressed through body language, careful word choice and acts such as giving the best seat or serving food first. At the same time, work ethic is strong, with small shops opening early, street vendors moving through neighborhoods from dawn and office workers commuting through heavy traffic to reach jobs in growing cities.

Community ties also shape how people in Vietnam interact. In urban neighborhoods, residents share news, watch children playing in alleys and support each other in family events such as weddings or funerals. In villages, communal houses or pagodas serve as centers for festivals and meetings. In workplaces, teamwork and harmony are often emphasized, and indirect communication may be preferred over open confrontation. These tendencies, however, differ by company culture, sector and generation.

Global media, tourism and the Vietnamese diaspora influence how the outside world views Vietnam country and people. Images of bustling street food stalls, scooter‑filled avenues, áo dài dresses, and stories about rapid economic growth or past war experiences all shape perceptions. At the same time, overseas Vietnamese communities contribute new elements to identity, mixing local traditions with influences from Europe, North America, Australia and other parts of Asia. It is important to remember that while certain social traits can be widely observed, individuals vary greatly in personality, beliefs and lifestyle.

Population, Demographics and Where People Live

How Many People Live in Vietnam Today?

As of the mid‑2020s, a rounded estimate is that a little over 100 million people live in Vietnam. This means the population is large but not as big as that of neighboring China, and similar in scale to countries such as Egypt or the Philippines. In recent decades, population growth has slowed because families, especially in cities, tend to have fewer children than in the past.

Fertility decline and better health care are gradually changing the age structure of Vietnam people. There are still many children and working‑age adults, but the share of older people is rising, and Vietnam is expected to become an ageing society in the coming decades. These trends affect social policies: the government and families must prepare for higher demand for pensions, long‑term care and geriatric health services, while also maintaining a productive workforce.

For the labor market, a still‑large working‑age population is an advantage, supporting manufacturing, services and agriculture. However, the shift to smaller families and urban living also raises questions about housing, schooling, child‑care and job creation in big cities. Understanding how many people live in Vietnam, and how this number is changing, is therefore central to planning for infrastructure, environment and social protection.

Age Structure, Life Expectancy and Urbanization

The age structure of Vietnam people can roughly be divided into three groups: children and teenagers under 15, working‑age adults from about 15 to 64, and older people aged 65 and above. Children and youth still make up a significant part of the population, which keeps schools full and creates demand for more teachers and facilities. Working‑age adults form the largest group, contributing to economic growth and supporting both younger and older generations.

The share of older citizens, while still smaller, is growing steadily as life expectancy improves. In the past, many people did not live far beyond their 50s or 60s, but now it is common to meet grandparents and great‑grandparents in the same family network. Life expectancy in Vietnam is in the mid‑70s on average, somewhat higher for women than for men. People in big cities often have better access to hospitals, specialist care and preventive services, so they may enjoy longer and healthier lives than some rural residents.

Urbanization in Vietnam has been rapid, especially since the 1990s. Hà Nội, Ho Chi Minh City, Hải Phòng, Đà Nẵng and Cần Thơ have expanded into surrounding farmland, drawing migrants from rural provinces who are seeking jobs and education. This movement has created dense residential districts, industrial parks and new suburban towns. The shift brings opportunities, such as higher incomes and better access to universities, but also challenges like traffic congestion, air pollution, rising rents and pressure on public transport. As a simple comparison, a person growing up in a small Mekong Delta village may commute by bicycle along canals, while a young worker in Ho Chi Minh City may spend more than an hour each day in motorbike traffic or on urban buses.

Regional Differences: Deltas, Cities and Uplands

Most Vietnam people live in river deltas and along the coast, where the land is flat and fertile. The Red River Delta around Hà Nội and Hải Phòng supports dense populations, intensive rice cultivation and a mix of traditional craft villages and modern industries. In the south, the Mekong Delta, including provinces like An Giang, Cần Thơ and Sóc Trăng, is famous for rice paddies, fruit orchards and waterways, but it also faces challenges from flooding, salinity and climate change.

Beyond these lowlands, upland and border regions in the north and Central Highlands have lower population density and are home to many ethnic minority groups. Provinces such as Hà Giang, Lào Cai and Điện Biên in the north, or Gia Lai and Đắk Lắk in the Central Highlands, include mountains, forests and plateau areas where communities practice terrace farming, shifting cultivation or coffee and rubber production. Economic opportunities here can be more limited, and access to health care, schools and markets often involves long travel distances.

These environmental variations influence housing styles, crops, cuisines and even local festivals, making Vietnam a country where geography is closely linked to how and where people live.

Climate also shapes regional life: the north has distinct cool and hot seasons, central coastal regions can be hit by typhoons, and the south is mostly tropical with rainy and dry periods. These environmental variations influence housing styles, crops, cuisines and even local festivals, making Vietnam a country where geography is closely linked to how and where people live.

Ethnic Groups and Languages in Vietnam

Major Ethnic Groups and the Kinh Majority

Vietnam officially recognizes 54 ethnic groups, of which the Kinh (also called Việt) form the majority. The Kinh make up around 85% of Vietnam people and are spread across most regions, especially in the lowlands, deltas and major cities. Vietnamese, the language of the Kinh, serves as the national language, used in government, education and national media.

The remaining 15% of the population belong to 53 ethnic minority groups. These communities enrich Vietnam country and people with diverse languages, musical traditions, clothing styles and belief systems. At the same time, some minority groups face obstacles in accessing services and having their voices heard in decision‑making due to geographic isolation or economic disadvantage.

| Ethnic Group | Approximate Share of Population | Main Regions |

|---|---|---|

| Kinh | ~85% | Nationwide, especially lowlands and cities |

| Tày | ~2% | Northern border provinces (Cao Bằng, Lạng Sơn) |

| Thái | ~2% | Northwest uplands (Sơn La, Điện Biên) |

| Mường | ~1.5% | Mid‑northern mountains (Hòa Bình, Thanh Hóa) |

| Hmong | ~1.5% | Northern highlands, some Central Highlands |

| Khmer | ~1.5% | Mekong Delta (Trà Vinh, Sóc Trăng) |

| Nùng | ~1.5% | Northern border areas |

These rough figures show that while the Kinh majority is very large, millions of people belong to other communities. Ethnic diversity contributes to Vietnam’s cultural richness through varied festivals, handicrafts, oral literature and agricultural techniques. For example, Thái and Tày stilt houses, Khmer pagodas in the Mekong Delta and Cham towers in central Vietnam are all visible markers of this diversity. At the same time, some minority areas have higher poverty rates, lower school completion and more limited transport connections, which can make it harder for residents to access public services or broader economic opportunities.

The state has introduced programs to support remote and minority regions through infrastructure investment, bilingual education and poverty reduction projects. Outcomes vary by locality, and discussions continue about how to respect cultural autonomy while promoting inclusive development. When speaking about Vietnam people, it is therefore more accurate to think of many peoples living within one national framework rather than a completely homogeneous society.

Hmong People and Other Upland Communities

Traditional Hmong livelihoods include growing maize, rice and other crops on steep hillsides, raising pigs and poultry, and producing textiles and silver jewelry. Houses are typically built of wood and earth, clustered on slopes above valleys and streams. Hmong clothing can be striking, with embroidered patterns, indigo‑dyed fabrics and bright headscarves; styles differ between subgroups such as White Hmong or Flower Hmong. Festivals often include music played on reed instruments, courtship songs and ritual animal offerings connected to ancestral spirits.

Other upland communities in Vietnam include the Dao, Thái, Nùng, Giáy and many smaller groups, each with their own languages and traditions. Many practice terrace rice farming, which turns mountain slopes into stepped fields, or combine wet‑rice agriculture in valleys with upland crops and forest products. Local markets, often held once or twice a week, are important social spaces where people trade livestock, cloth, tools and food, and where young people may meet partners.

However, it is important not to romanticize life in these regions. Many upland households face constraints such as limited access to quality schools, distance to health clinics, lack of stable wage jobs and vulnerability to landslides or harsh weather. Some young people migrate seasonally or long‑term to cities and industrial zones to work in factories or services, sending money home to support their families. The challenges and adaptation strategies of Hmong and other upland groups show how geography, culture and development are closely linked for Vietnam people.

Vietnamese Language and Other Languages Spoken in Vietnam

The Vietnamese language belongs to the Austroasiatic language family and has developed through contact with Chinese, neighboring Southeast Asian languages and, more recently, European languages. It is a tonal language, which means that pitch patterns help distinguish word meanings; most dialects use six tones. For many international learners, tones and certain consonant sounds are the main challenges, but grammar is relatively simple compared to some other languages, with no verb conjugation by person or number.

Modern written Vietnamese uses a Latin‑based script called Quốc Ngữ, created by missionaries and scholars several centuries ago and widely adopted in the early 20th century. This script uses letters similar to those in European alphabets, with additional diacritic marks to indicate tones and vowel qualities. The use of Quốc Ngữ has supported high literacy rates because it is easier to learn than earlier scripts that were based on Chinese characters.

Alongside Vietnamese, many other languages are spoken among Vietnam people. Tày, Thái and Nùng languages are related to the Tai‑Kadai family, Hmong belongs to the Hmong‑Mien family, and Khmer and some others are also Austroasiatic. In many upland or border regions, people grow up bilingual or multilingual, speaking their ethnic language at home and Vietnamese in school and official settings. In southern and central provinces, one may also hear Cham, Chinese dialects and various migrant tongues.

Language use is closely connected to identity and opportunity. Knowing Vietnamese is essential for education, formal employment and communication with state institutions. At the same time, maintaining minority languages helps sustain oral histories, songs and spiritual practices. For visitors, learning a few Vietnamese phrases, such as greetings and polite forms of address, can greatly improve interactions, even when many younger people have studied English or other foreign languages.

Historical Origins and Formation of Vietnamese Identity

From Early Cultures to Independent Kingdoms

The roots of Vietnamese identity stretch back to early cultures in the Red River Delta and surrounding valleys. Archaeological finds from the Đông Sơn culture, dating from roughly the first millennium BCE, include bronze drums, weapons and tools that show advanced metalworking and organized societies. Legends speak of the kingdom of Văn Lang, ruled by the Hùng kings, as an early political formation in this region.

For many centuries, parts of what is now northern Vietnam came under the control of Chinese dynasties. This period brought Confucian learning, Chinese characters, administrative models and new technologies, but it also saw waves of resistance by local leaders who sought autonomy. In the 10th century, figures such as Ngô Quyền achieved lasting independence after key victories, and independent Vietnamese states emerged under dynasties like the Lý, Trần and Lê, using the name Đại Việt at various times.

These early independent kingdoms expanded gradually southward, incorporating lands previously inhabited by the Cham and Khmer. Over time, shared experiences of defending territory, cultivating rice in wet fields and honoring ancestral and village spirits contributed to a sense of common identity among many communities. While local dialects and customs remained diverse, ideas about a Vietnamese homeland and people took shape through royal chronicles, temple inscriptions and village traditions.

Chinese, Southeast Asian and Western Influences

Vietnamese culture developed through a long process of adaptation and selective borrowing rather than passive reception of outside models. From China came Confucianism, with its teachings on hierarchy, filial piety and moral governance, as well as Mahayana Buddhism and Taoist practices. Classical education for centuries relied on Chinese characters, and imperial examinations selected scholar‑officials who memorized Confucian texts. These influences shaped family values, legal codes and ideas of proper behavior.

At the same time, Vietnam interacted with other Southeast Asian societies through trade, marriage alliances and warfare. Contacts with Champa, the Khmer Empire and later regional polities contributed to shared temple forms, maritime trade networks and cultural practices such as certain musical instruments or architectural styles. The southward expansion of Vietnamese kingdoms into territories once dominated by Cham and Khmer populations created multi‑ethnic frontiers that still shape Vietnam country and people today.

Western contact, especially with France in the 19th and early 20th centuries, introduced new political and economic structures. French colonial rule brought Catholic missions, plantation agriculture, railways, modern ports and urban planning in cities like Hà Nội and Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City). At the same time, colonialism disrupted local economies, imposed unequal power relations and sparked nationalist movements. Western ideas of nationalism, socialism and republicanism influenced Vietnamese intellectuals who later led independence struggles. The Latin‑based Quốc Ngữ script, promoted during this period, later became a tool for mass education and modern literature.

War, Division and Migration in the 20th Century

The 20th century was marked by intense conflict and transformation for Vietnam people. After World War II, movements for independence challenged French colonial control, leading to the First Indochina War and the eventual withdrawal of France in the mid‑1950s. Vietnam was then divided into a northern and a southern state, each with its own political system and international alliances. This division set the stage for what is widely known as the Vietnam War, involving large‑scale fighting, aerial bombardment and foreign military forces.

War affected almost every aspect of life: many families lost relatives, cities and villages were damaged, and food supplies were disrupted. After the war ended and the country was reunified in 1975, Vietnam experienced further changes, including economic difficulties, reorganization of land and enterprises, and new regional patterns of power. These factors, combined with political concerns and fear of reprisals, led some Vietnam people to move internally or leave the country altogether.

Large numbers of refugees, often called Vietnamese boat people, fled by sea or crossed borders by land during the late 1970s and 1980s. Many were later resettled in countries such as the United States, Australia, France and Canada, forming important Vietnamese diaspora communities. These migrations reshaped families, created new transnational ties and added another layer to Vietnamese identity, which now extends far beyond the borders of the homeland.

Family Life, Values and Everyday Social Norms

Family Structure and Filial Piety

Family is at the center of social life for many Vietnam people. While household patterns are changing, it is common to find multi‑generational arrangements in which grandparents, parents and children live in the same home or nearby. Even when young adults move to cities or abroad, they often maintain close contact with parents and relatives through frequent phone calls, online messaging and return visits during major holidays such as Tết (Lunar New Year).

The concept of filial piety, influenced by Confucian thought and local tradition, emphasizes respect, obedience and care toward parents and ancestors. Children are taught from a young age to listen to elders, help with household tasks and honor family sacrifices. As parents age, adult children are expected to support them financially and emotionally. Ancestor worship, practiced through household altars and graveside visits, extends these obligations to past generations and keeps family history alive.

Family decisions about education, work and marriage are often made collectively rather than individually. A teenager choosing a high school track or university major may discuss options with parents, aunts, uncles and grandparents. When young people plan to marry, families on both sides commonly meet, exchange gifts and consider compatibility not only between the couple but also between extended families. To visitors from more individualistic societies, these practices may feel restrictive; for many Vietnam people, they provide security, guidance and a sense of belonging.

Gender Roles and Generational Change

Traditional gender roles in Vietnam have expected men to be primary breadwinners and decision‑makers, and women to take major responsibility for domestic work and child‑rearing. In rural areas, women often combine farming, market selling and household duties, while men handle tasks such as plowing, heavy labor or representing the family in official matters. Cultural ideals sometimes praise women as hardworking, patient and self‑sacrificing, while expecting men to be strong and ambitious.

Economic growth, higher education and globalization are reshaping these patterns, especially among younger generations and in cities. Many women now pursue university degrees, professional careers and leadership positions. It is increasingly common to see female office managers, engineers and entrepreneurs in Hà Nội, Ho Chi Minh City and other urban centers. Men participate more in childcare and household tasks, particularly in families where both partners work in full‑time jobs.

However, change is uneven. In both urban and rural contexts, women often carry a “double burden” of paid work and unpaid care, and they may face barriers in career advancement or wage equality. Social expectations can still pressure women to marry and have children by a certain age, while unmarried men may face questions about their ability to support a family. Migration for work also affects gender roles: in some industrial zones, large numbers of young women work in factories and send remittances home, while grandparents or other relatives care for their children in villages. These shifts create new opportunities and tensions in how Vietnam people think about masculinity, femininity and family responsibility.

Daily Life in Urban and Rural Vietnam

Everyday routines for people in Vietnam differ by location, occupation and income, but some general patterns can be described. In a large city like Ho Chi Minh City, many residents start their day with a quick breakfast of phở, bánh mì or sticky rice bought from a street vendor.

In rural villages, especially in agricultural regions, daily life follows the rhythms of farming and local markets. Farmers may rise before sunrise to plant, tend or harvest rice and other crops, relying on monsoon rains or irrigation channels. Women might prepare meals, care for children and sell produce in nearby markets, while men perform tasks such as plowing or repairing tools. Community events, such as weddings, funerals and festivals, are major social occasions that can last several days and involve shared cooking, music and rituals.

Across both urban and rural settings, smartphones, internet access and social media are changing habits and social connections. Young people use messaging apps, video platforms and online games to communicate with friends, follow trends and learn new skills. Many adults use mobile banking, ride‑hailing services and e‑commerce platforms. At the same time, some elders may prefer face‑to‑face interactions and traditional media such as television and radio. These differences can create generation gaps in communication style, but they also enable Vietnam people to connect with relatives abroad and access global information in ways that were impossible a few decades ago.

Religion, Ancestor Worship and Folk Beliefs

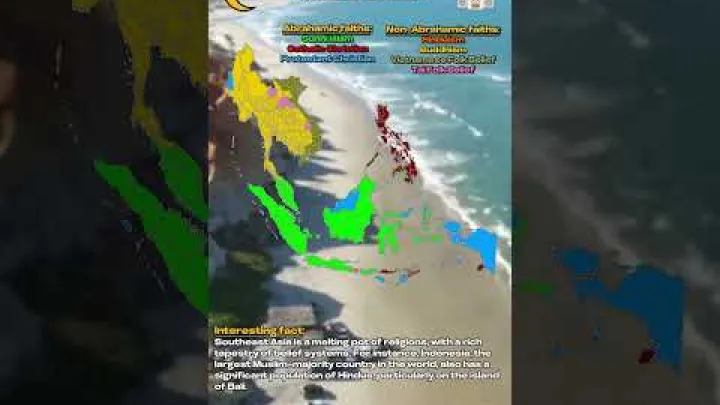

The Three Teachings and Folk Religion

Religious life in Vietnam is often described as a blend rather than a set of strictly separate traditions. The “Three Teachings” of Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism have interacted with older folk beliefs and local spirit worship. Many Vietnam people draw from all three sources in their moral outlook and spiritual practice, even if they do not identify as followers of any formal religion.

In daily life, this mixture appears in practical ways. People may visit a pagoda to light incense and pray for health or exam success, while also following Confucian ideas about respect for elders and social harmony. Taoist elements can be seen in practices related to feng shui, astrology or the selection of auspicious dates. Meanwhile, folk religion includes belief in village guardian spirits, mother goddesses, mountain and river deities, and various household gods. Ritual specialists, such as fortune‑tellers or spirit mediums, may be consulted for guidance.

Because many practices are family‑based and not tied to membership lists, surveys often classify a large share of Vietnam people as “non‑religious.” This label can be misleading, since it may include people who maintain altars at home, attend festivals and perform rituals at important life stages. A more accurate description is that many people in Vietnam participate in a flexible, layered religious culture that combines moral teachings, ritual obligations and personal beliefs without strict boundaries.

Ancestor Worship and Household Altars

Ancestor worship is one of the most widespread and meaningful spiritual practices among Vietnam people. It reflects the idea that family bonds continue beyond death and that ancestors can protect, advise or influence the fortunes of living descendants. Nearly every Vietnamese household, whether in a city apartment or a rural home, has some form of ancestral altar.

A typical household altar is placed in a respectful location, often in the main room or on an upper floor. It may hold framed photos of deceased relatives, lacquered name tablets, and offerings such as fruit, flowers, tea, rice wine and sometimes favorite foods of the ancestors. Incense sticks are lit regularly, especially on the first and fifteenth days of the lunar month, as well as on death anniversaries and major festivals. When someone lights incense, they often bow several times and silently express wishes or gratitude.

Certain dates are especially important in ancestor worship. Death anniversaries (giỗ) are marked with special meals where family members gather, prepare dishes the ancestor liked, and invite the spirit to join the feast through ritual words and offerings. During Tết, families clean graves, decorate altars and “invite” ancestors to return home for the New Year celebration. At the end of the holiday, they perform rituals to “see off” the ancestral spirits back to their realm. These practices reinforce family continuity, teach younger generations about their lineage and give people a framework for remembering loss in a supportive community setting.

Other Religions in Vietnam Today

Alongside folk religion and Buddhist‑influenced practices, Vietnam is home to several organized religions. Mahayana Buddhism is the largest of these, with pagodas across the country and monks and nuns playing roles in community life, education and charity. Catholicism, introduced centuries ago and shaped during the colonial period, has a significant presence, particularly in some northern and central provinces and parts of the south. Catholic parishes often run schools and social services and celebrate major feasts such as Christmas and Easter with large gatherings.

Protestant communities are smaller but growing in some urban areas and among certain ethnic groups in the highlands. Vietnam is also the birthplace of Cao Đài, a syncretic religion founded in the 20th century that combines elements of Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism and Christianity, and of Hòa Hảo, a reformist Buddhist movement based mainly in the Mekong Delta. Theravāda Buddhism is practiced among Khmer communities in southern Vietnam, with temples resembling those in neighboring Cambodia and Thailand.

In addition, there are Muslim communities, particularly among the Cham people in central and southern regions, and smaller groups in cities due to migration. Religious organizations operate within a system of state registration and oversight, guided by laws on belief and religion. This framework seeks to recognize religious freedom while monitoring activities for social order, and it shapes how Vietnam people practice their faiths in public and private spaces. Exact percentages for each religion vary across surveys, but it is clear that Vietnam’s religious landscape is plural and dynamic.

Culture, Festivals and Traditional Arts

National Clothing and Symbols: Áo Dài and More

The áo dài, a long, fitted tunic worn over trousers, is one of the most recognizable symbols associated with Vietnam people. It is often seen as elegant and modest, and is commonly worn by women for formal events, school ceremonies, weddings and cultural performances. In some schools and offices, especially in the central city of Huế and in certain service industries, the áo dài serves as a uniform. There are also male versions of the áo dài, usually worn for ceremonial occasions.

Traditional clothing varies widely by region and ethnic group. In northern uplands, Hmong, Dao and Thái communities have distinctive embroidered outfits, headpieces and silver ornaments that are particularly prominent during festivals. In the Mekong Delta, Khmer people wear garments that resemble those in Cambodia, while Cham communities have their own styles influenced by Islamic norms. Colors often carry symbolic meanings; for instance, red and gold are associated with good fortune and are common in New Year decorations and wedding attire.

National symbols appear in public life, festivals and monuments. The lotus flower is widely used in art and architecture as a symbol of purity rising from muddy waters. Bronze drum motifs from the Đông Sơn culture decorate government buildings, museums and cultural centers, linking modern Vietnam people with ancient heritage. In everyday life, however, most people wear modern, casual clothes such as jeans, T‑shirts and business attire, reserving traditional outfits mainly for special occasions.

Music, Theater and Martial Arts

Vietnam’s musical and theatrical traditions reflect both local histories and broader Asian influences. In the northern provinces, quan họ folk songs, often performed in call‑and‑response style by male and female duets, express themes of love, friendship and village solidarity. In some regions, ca trù features female vocalists accompanied by traditional instruments, with a history connected to court entertainment and scholarly gatherings. These genres require skilled singing techniques and are recognized as important intangible cultural heritage.

In the south, cải lương, a form of modern folk opera, combines traditional melodies with Western instruments and narrative plots about family drama, social change and historical events. Water puppetry, originating in the Red River Delta, uses wooden puppets controlled by long poles hidden under the water’s surface. Performances often depict everyday rural life, legends and humorous scenes, accompanied by live music and singing. Visitors to Hà Nội, for example, can attend water puppet shows that introduce these stories to both local and international audiences.

Martial arts are another cultural domain where Vietnam people express discipline, health and pride. Vovinam, a Vietnamese martial art founded in the 20th century, combines strikes, grappling and acrobatics, and emphasizes mental training and community spirit. There are also older regional martial traditions associated with particular villages or lineages, sometimes performed in festivals or demonstrations. Training in martial arts can help young people build confidence and physical fitness, while also connecting them to national narratives of resistance and self‑defense.

Major Festivals: Tết, Mid-Autumn and Local Celebrations

Festivals are central to the cultural life of Vietnam country and people, bringing families and communities together for rituals, food and entertainment. The most important celebration is Tết Nguyên Đán, or Lunar New Year, usually occurring between late January and mid‑February. In the weeks before Tết, people clean and decorate their homes, buy new clothes, prepare special foods and travel long distances to reunite with family.

Key customs during Tết include:

- Offering food, flowers and incense at ancestral altars to invite ancestors to join the celebration.

- Giving red envelopes with money (lì xì) to children and sometimes to elders as a wish for luck and prosperity.

- Visiting relatives, neighbors and teachers to exchange New Year greetings.

- Enjoying traditional dishes such as bánh chưng (square sticky rice cake) in the north or bánh tét (cylindrical version) in the south.

The Mid‑Autumn Festival, held on the 15th day of the eighth lunar month, is especially focused on children. Streets and schoolyards fill with lantern processions, lion dances and moon‑gazing activities. Children receive toys and mooncakes, and families celebrate the harvest season. This festival emphasizes joy, family warmth and the idea that children are “the moon of the nation.”

In addition to these national holidays, many local festivals honor village guardian spirits, historical heroes or deities linked to agriculture and water. For example, some coastal communities hold whale worship ceremonies to pray for protection at sea, while others celebrate boat races, buffalo fights or rice harvest rites. These events maintain local identity and give Vietnam people opportunities to express gratitude, hope and communal pride.

Vietnamese Cuisine and the Way People Eat

Meals are usually shared, with common dishes placed in the center of the table and individual bowls of rice. Family members or friends pick small portions from shared plates, creating a sense of togetherness and encouraging conversation. This style of eating reflects ideas about balance, moderation and social harmony.

Rice is the staple food, but the variety of dishes is wide and regionally diverse. In the north, flavors are often mild and subtle, with dishes like phở (noodle soup) and bún chả (grilled pork with noodles). Central Vietnam is known for spicier and more complex preparations, such as bún bò Huế (spicy beef noodle soup). The south favors sweeter tastes and abundant fresh herbs in dishes like gỏi cuốn (fresh spring rolls) or bún thịt nướng (grilled pork with vermicelli). Fish sauce (nước mắm) is a key seasoning nationwide, providing a salty, umami flavor.

Vietnamese cuisine emphasizes the balance of flavors (salty, sweet, sour, bitter and umami) and the use of fresh ingredients. Herbs like basil, coriander, perilla and mint are common, as are vegetables and tropical fruits. Many people see food not only as nourishment but also as a way to maintain health, with attention to “hot” and “cool” qualities of dishes in traditional understanding. Street food culture is vibrant, with small vendors providing affordable meals to workers and students. For visitors, observing how people in Vietnam gather around low plastic stools on sidewalks, share soups and grilled dishes, and linger over iced tea or coffee gives insight into social life as much as into taste.

Vietnamese Diaspora and Boat People

Who Are the Vietnamese Boat People?

The term “Vietnamese boat people” refers to refugees who fled Vietnam by sea, mainly after the end of the Vietnam War in 1975. They left the country in large numbers during the late 1970s and 1980s, using small boats to cross the South China Sea and reach neighboring countries such as Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines and Hong Kong. Many hoped to be accepted for resettlement in distant countries.

Reasons for this mass departure included political concerns, fear of punishment for association with the former South Vietnamese government or military, economic hardship and a desire for greater freedom and security. The journeys were extremely risky: overcrowded boats faced storms, mechanical failures, piracy and lack of food or water. Many people died at sea or suffered severe trauma. International organizations and governments eventually organized refugee camps and resettlement programs, helping hundreds of thousands of Vietnam people start new lives abroad.

Where Do Vietnamese People Live Around the World?

Today, there are large Vietnamese diaspora communities across the globe. The biggest concentration is in the United States, where several million people of Vietnamese origin live, especially in states like California and Texas. Cities such as Westminster and Garden Grove in California have well‑known “Little Saigon” neighborhoods with Vietnamese shops, restaurants, temples and media outlets.

Other significant communities exist in countries such as France, Australia, Canada and Germany, reflecting both historical ties and refugee resettlement patterns. In France, Vietnamese communities date back to colonial times and were reinforced after 1975; in Australia and Canada, many boat people and their descendants have become active in business, academia and politics. In parts of Asia, such as Taiwan, South Korea and Japan, more recent migrants work in manufacturing, construction, services or study in universities, adding another layer to the global presence of Vietnam people.

Remittances sent to relatives in Vietnam help finance education, healthcare, housing and small businesses. Travel between homeland and diaspora areas has increased as visa policies eased and incomes rose. Online communication, social media groups and Vietnamese‑language media allow people to share news, cultural content and political views across continents.

These communities maintain strong transnational connections. Remittances sent to relatives in Vietnam help finance education, healthcare, housing and small businesses. Travel between homeland and diaspora areas has increased as visa policies eased and incomes rose. Online communication, social media groups and Vietnamese‑language media allow people to share news, cultural content and political views across continents.

Life Between Vietnam and Overseas Communities

Life for Vietnamese people abroad often involves navigating multiple identities. First‑generation refugees and migrants may retain strong ties to their birthplaces, cook traditional foods, speak Vietnamese at home and participate in community organizations that preserve cultural practices. Second‑generation and mixed‑heritage individuals sometimes balance Vietnamese and host‑country cultures, speaking multiple languages and adapting to different social expectations in school, work and family life.

Cultural institutions such as language schools, Buddhist temples, Catholic churches, youth associations and student clubs help maintain connections to Vietnamese heritage. Festivals like Tết and Mid‑Autumn are celebrated in diaspora communities with lion dances, food fairs and cultural performances. These events allow younger people who have never lived in Vietnam to experience some aspects of Vietnam country and people.

Contact is not one‑way. Overseas Vietnamese influence life in Vietnam through investments, returning expertise and cultural exchange. Entrepreneurs may open cafes, technology startups or social enterprises after working abroad. Artists and musicians produce works that reflect both Vietnamese roots and global trends. Return visits for family events or tourism expose local relatives to new ideas about education, gender roles and civic engagement. In this way, the story of Vietnam people today includes both those who live within the country’s borders and those who move between multiple homes.

Education, Health and Economy: How Vietnam Is Changing

Education and the Importance of Schooling

Education holds a central place in the aspirations of Vietnam people. Parents often see schooling as the main path to a better life for their children, and they invest considerable time, money and emotional energy in academic success. Stories of students from modest backgrounds who achieve high exam scores and enter prestigious universities are widely admired and shared in the media.

The formal education system includes preschool, primary school, lower secondary, upper secondary and higher education at universities and colleges. Attendance in basic education is high, and literacy rates are among the strongest in the developing world. Vietnamese students have achieved notable results in international assessments in subjects like mathematics and science, demonstrating the effects of strong foundational education and disciplined study habits.

However, the system also faces challenges. In rural and remote areas, school facilities may be less well equipped, and teachers may have fewer resources. Some children must travel long distances or cross rivers to attend class, which can reduce attendance during bad weather. Exam pressure is intense, especially for high‑stakes tests that decide entry into selective schools or universities. Many families pay for private tutoring or after‑school classes to prepare their children, which can add financial strain and limit leisure time. Higher education is expanding but still struggles with issues like overcrowded classrooms, limited research funding and the need to better match training with labor market demands.

Health, Life Expectancy and Health Care Access

Over the past few decades, Vietnam has achieved significant improvements in public health. Life expectancy has increased into the mid‑70s, and infant and maternal mortality rates have fallen sharply compared with earlier generations. Expanded vaccination programs, better control of infectious diseases and improved nutrition have all contributed to these gains. Many Vietnam people now live longer and healthier lives than their parents and grandparents did.

The health care system combines public hospitals and clinics with a growing private sector. Health insurance coverage has expanded, with many citizens enrolled in social health insurance schemes that help cover the costs of basic services. Community health stations in rural areas provide vaccinations, maternal care and treatment for common conditions, while larger urban hospitals offer more specialized services. Private clinics and pharmacies play an important role, particularly for outpatient care in cities.

Despite progress, gaps remain. Rural and upland communities may have fewer medical staff, limited equipment and long travel times to reach hospitals. Out‑of‑pocket costs can still be high for surgery, long‑term treatment or medicines not covered by insurance, leading some households into debt. As Vietnam people live longer, non‑communicable diseases such as diabetes, heart disease and cancer are becoming more common, placing new demands on the health system. Environmental challenges, including air pollution in cities and contamination of water sources in some industrial or agricultural areas, also affect health. Addressing these issues is an important part of Vietnam’s ongoing social development.

Work, Income and Vietnam’s Rapid Economic Growth

Since the introduction of economic reforms in the late 1980s, Vietnam has moved from a largely state‑run, centrally planned economy to a more market‑oriented system integrated into global trade. This transition has significantly changed the work and income patterns of Vietnam people. Many households that once relied solely on subsistence agriculture now combine farming with wage labor, small businesses or remittances from family members working in cities or abroad.

Key sectors in today’s economy include manufacturing, services and agriculture. Industrial zones around major cities produce electronics, garments, footwear and other goods for export. Service industries such as tourism, retail, finance and information technology are expanding, especially in urban centers. Agriculture remains important for employment and food security, with rice, coffee, rubber, pepper and seafood among major products. In recent years, digital work, online commerce and startup culture have created new opportunities for young Vietnam people, particularly those with higher education and foreign language skills.

Economic growth has reduced poverty and increased average incomes, but not everyone benefits equally. Some regions and groups, particularly in remote upland areas, have seen slower improvements. Informal work, without stable contracts or social protection, remains common in sectors like construction, street vending and domestic service. Income inequality has widened between high‑income urban households and low‑income rural families. Environmental stress is also a concern: rapid industrialization and urbanization have contributed to pollution, and climate‑related risks such as sea‑level rise, saltwater intrusion and extreme weather events threaten livelihoods in deltas and coastal zones. Balancing growth with social equity and environmental sustainability is a major challenge facing Vietnam country and people in the coming decades.

War, Loss and Historical Memory

How Many People Died in the Vietnam War?

Estimates suggest that between 2 and 3 million Vietnamese people, including both civilians and soldiers from North and South Vietnam, died during the Vietnam War. When adding casualties from neighboring Laos and Cambodia, as well as foreign militaries, the total number of deaths becomes even higher. Around 58,000 American soldiers were killed, along with tens of thousands of soldiers from allied countries such as South Korea, Australia and others.

It is difficult to determine exact numbers because records from wartime were incomplete, destroyed or never created, and many deaths occurred in remote areas or during chaotic circumstances. Bombing, ground combat, forced displacement, hunger and disease all contributed to the human toll. When people ask how many Vietnamese people were killed in the Vietnam War, the answer is therefore given as a range rather than a single precise figure, out of respect for the complexity and scale of the suffering.

Conscription and the Draft During the War

During the Vietnam War, both the northern and southern governments used conscription, or compulsory military service, to build their armed forces. Young men of certain ages were required to register, undergo health checks and, if selected, serve in the army or related units. Some volunteered willingly due to patriotism, family tradition or social pressure, while others were drafted against their personal wishes. In many villages, nearly every family had at least one member in uniform, and some had several.

Foreign countries involved in the conflict also used draft systems. In the United States, for example, hundreds of thousands of young men were conscripted under the Selective Service System, while others served as volunteers. Debates about fairness, deferments and conscientious objection were intense in those societies. In Vietnam itself, precise numbers of people drafted on each side are hard to establish because archives are incomplete and definitions of “draftee” versus “volunteer” vary.

Military service had long‑lasting effects on Vietnam people. Many soldiers were wounded or disabled, and families lost breadwinners and loved ones. Youth who might have been in school or learning trades instead spent years in combat or related duties, affecting their later education and career paths. After the war, veterans often faced challenges in reintegrating into civilian life, dealing with physical and psychological scars, and adapting to new political and economic realities.

How the War Still Shapes Vietnamese People Today

Although several decades have passed since the end of the Vietnam War, its memory remains strong in Vietnamese society. Monuments, cemeteries and museums across the country honor those who died and educate younger generations about the conflict. Families keep photos of deceased relatives on household altars, tell stories about their experiences and mark death anniversaries with rituals and shared meals. Literature, films and songs continue to reflect themes of sacrifice, loss and longing for peace.

Environmental and health legacies also persist. Unexploded ordnance remains in some former battlefields, posing risks to farmers and children, and efforts to clear these hazards continue with domestic and international support. Chemicals used during the war, such as Agent Orange, have been associated with long‑term health problems and disabilities in affected areas, leading to ongoing medical and social assistance programs.

At the same time, younger generations of Vietnam people increasingly focus on economic development, education and international cooperation. Many have no direct memory of the war and instead encounter it through textbooks, movies and family narratives. Projects that promote reconciliation, such as joint research on missing soldiers, cultural exchanges, veteran visits and partnerships between former adversary countries, show how societies can look forward while acknowledging the past. For visitors, understanding how history lives in daily life can deepen respect for the resilience and aspirations of people in Vietnam today.

Frequently Asked Questions

Common Questions About Vietnam People and Their Way of Life

This section gathers brief answers to questions that readers often ask about Vietnam country and people. It covers topics such as population size, ethnic diversity, religion, family customs, Hmong people in Vietnam, the Vietnamese boat people and war casualties. These answers provide quick reference points and can be used as a starting place before exploring the more detailed sections above.

The questions reflect the concerns of travelers who plan to visit, students who study Vietnamese history and culture, and professionals who may work with Vietnamese colleagues or communities. While the responses are concise, they aim to be accurate, neutral and easy to translate into other languages. For deeper understanding, readers can connect each answer with the relevant part of the article where the topic is discussed in more detail.

What is the current population of Vietnam and how is it changing?

Vietnam’s population is just over 100 million people and continues to grow slowly. Growth has decreased compared with the 1960s because families have fewer children. The share of older people is rising, so Vietnam is becoming an ageing society. Most people still live in lowland and delta regions, but cities are expanding quickly.

What are the main ethnic groups among the people of Vietnam?

The largest ethnic group in Vietnam is the Kinh, who make up about 85% of the population. There are 53 officially recognized minority groups, including the Tày, Thái, Mường, Hmong, Khmer and Nùng. Many minority communities live in mountainous and border regions in the north and Central Highlands. These groups have distinct languages, clothing, rituals and farming systems.

What religion do most people in Vietnam follow today?

Most people in Vietnam follow a mix of folk religion, ancestor worship and elements of Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism rather than one single organized faith. Surveys often show a large share of the population as “non‑religious”, but many of these people still keep ancestral altars, visit temples and follow spiritual rituals. Buddhism, especially the Mahayana tradition, is the largest formal religion, followed by Catholicism and smaller groups such as Protestants, Caodaists and Hoa Hảo Buddhists.

What are Vietnamese family values and social customs like?

Vietnamese family values emphasize respect for elders, strong ties between generations and a duty to care for parents and ancestors. Decisions about education, work and marriage traditionally consider the interests of the whole family, not just the individual. Everyday customs highlight politeness and hierarchy, for example through careful use of pronouns and honorifics. Urbanization is changing gender roles and youth lifestyles, but filial piety and family loyalty remain very important.

Who are the Hmong people in Vietnam and where do they live?

The Hmong are one of Vietnam’s larger ethnic minority groups, accounting for about 1.5% of the population. They mainly live in high mountain areas of northern Vietnam, such as Hà Giang, Lào Cai and Sơn La provinces. Many Hmong communities practice terrace farming and maintain distinctive traditional clothing, music and rituals. Some Hmong also live in Central Highlands regions due to more recent migration.

Who were the Vietnamese “boat people” and why did they leave Vietnam?

The Vietnamese “boat people” were refugees who fled Vietnam by sea after the end of the Vietnam War in 1975, mainly during the late 1970s and 1980s. They left for many reasons, including political persecution, economic hardship and fear of punishment for past ties to the former South Vietnamese state. Many faced dangerous journeys and lived in refugee camps before resettling in countries such as the United States, Canada, Australia and France. Their descendants form a large part of the modern Vietnamese diaspora.

How many people were killed in the Vietnam War, including Vietnamese civilians and soldiers?

Researchers estimate that between 2 and 3 million Vietnamese people, including both civilians and soldiers from North and South Vietnam, were killed in the Vietnam War. Around 58,000 American soldiers also died, along with tens of thousands of soldiers from other allied countries. Exact numbers are difficult to determine because of incomplete records and the nature of the conflict. The human and social costs of the war are still deeply remembered in Vietnam and abroad.

Who are some of the most famous Vietnamese people in history and modern times?

Well‑known historical Vietnamese figures include national hero Trần Hưng Đạo, poet and scholar Nguyễn Trãi, and Hồ Chí Minh, who led the struggle for independence and national reunification. Modern famous Vietnamese people include writer and peace activist Thích Nhất Hạnh, mathematician Ngô Bảo Châu, and many internationally recognized artists, business leaders and athletes. Overseas Vietnamese such as actress Kelly Marie Tran and chef Nguyễn Tấn Cường (Luke Nguyen) also help introduce Vietnamese culture globally.

Conclusion and Key Takeaways About Vietnam People

What We Learn From Studying Vietnam’s People and Society

Looking across history, culture and daily life, a complex picture of Vietnam people emerges. They live in a geographically varied country of more than 100 million inhabitants, dominated by the Kinh majority but enriched by 53 other ethnic groups. Vietnamese identity grew out of early riverine cultures, long interaction with China and Southeast Asia, colonial encounters and the profound experiences of war, division and migration in the 20th century.

Family values, filial piety and ancestor worship provide continuity, while religious practices blend the Three Teachings with local spirit beliefs and organized faiths such as Buddhism and Catholicism. Education, health improvements and economic reforms have transformed opportunities for many people in Vietnam, even as inequalities and environmental pressures remain. Diaspora communities and the legacy of the Vietnamese boat people show that the story of Vietnam country and people now spans continents.

Understanding these dimensions helps travelers behave respectfully, supports students in interpreting historical events and assists professionals in building effective partnerships. Rather than reducing “Vietnam people” to simple stereotypes, this perspective highlights diversity, resilience and ongoing change in a society that continues to evolve.

Continuing to Explore Vietnam Country and People

The picture presented here is necessarily broad, and many topics invite further exploration. Each ethnic group has its own detailed history and artistic traditions; each region has distinctive landscapes, dialects and cuisines. Festivals such as Tết or local village celebrations reveal layers of belief and community that reward careful observation, while Vietnamese literature, film and contemporary art offer rich insights into how people see themselves and the world.

For those interested in learning more, useful paths include visiting museums and historical sites, reading oral histories and novels by Vietnamese authors, and attending cultural events organized by Vietnamese communities at home or abroad. Engaging with both older and younger generations, in Vietnam and in the diaspora, can deepen understanding of how memories of the past and hopes for the future coexist. As Vietnam country and people continue to change, any portrait remains partial, but careful attention and openness can bring us closer to the lived realities behind the statistics and headlines.

Your Nearby Location

Your Favorite

Post content

All posting is Free of charge and registration is Not required.