Vietnam House: Traditional Homes, Modern Design, and Housing Market Guide

For international readers, it also connects to questions about how much a house in Vietnam costs, where to rent, and what daily life inside these homes feels like. Understanding Vietnam houses means looking at culture, climate, architecture, and the housing market at the same time. This guide introduces the main house types, explains design ideas, and outlines key points on prices, buying, and renting for visitors, students, and people planning a longer stay.

Introduction to the Vietnam house concept

Why Vietnam house matters for culture, lifestyle, and investment

When people talk about a Vietnam house, they are usually talking about more than walls and a roof. Vietnamese houses reflect family structures, neighborhood relationships, religious practice, and attitudes toward nature. A traditional wooden house with a central courtyard, for example, is both a place to live and a place to worship ancestors, host relatives, and celebrate festivals. Even in a small city apartment, you will often see a family altar, plants on the balcony, and clever ways to create privacy for several generations living together.

At the same time, rural areas still have simple brick, bamboo, or stilt houses that follow older building traditions. For investors and long-term residents, choosing a Vietnam house is closely linked to long-term financial planning, because land and property ownership can be a major store of value in a growing economy.

Different audiences are interested in these houses for different reasons. Students and remote workers usually focus on rental Vietnam houses or apartments in convenient city neighborhoods, where internet quality, safety, and noise levels matter as much as price. Foreign buyers look at Vietnam houses for sale in both major cities and emerging provincial towns, comparing long-term prospects, legal conditions, and lifestyle quality.

Housing choices also reflect broader shifts in Vietnam’s economy and its integration with the world. In large cities, international-style condominiums sit next to traditional markets and old tube houses. New projects advertise green design, smart home technology, and community amenities, while older areas still rely on small-scale shops and informal shared spaces. Understanding these contrasts helps readers make sense of what they see on the street and in property listings, and it can guide better decisions about where and how to live in Vietnam.

Overview of main types of Vietnam houses today

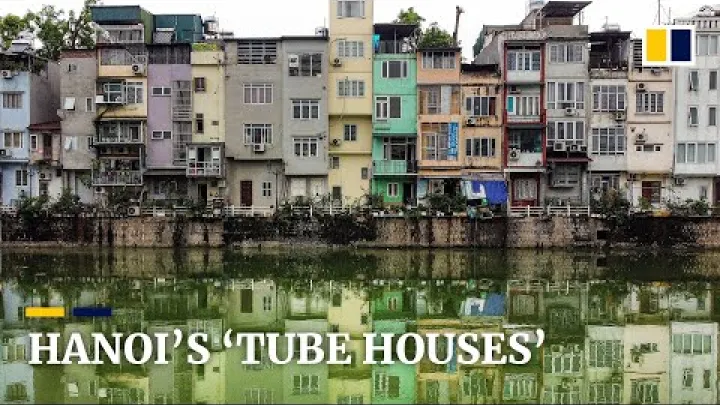

Across the country, several main categories of Vietnam house appear again and again, even though details differ between regions. Traditional wooden houses, including courtyard houses, stilt houses, and Ruong houses, are still found in villages and heritage towns. In big cities, the most common residential form is the urban tube house: a very narrow but deep house, often several stories high, attached to neighbors on both sides. Alongside these are apartment buildings ranging from simple walk-up blocks to modern high-rise towers, plus suburban or villa-style homes in new planned areas.

Geography and climate strongly influence which house type dominates in each place. In the north, winters are cooler and summers hot and humid, so houses often have thick brick walls, tiled roofs, and enclosed courtyards to buffer temperature changes. Along the central coast, where storms and typhoons are frequent, Ruong houses and other traditional forms use strong wooden frames, raised floors, and heavy roofs designed to resist high winds. In the southern lowlands and the Mekong Delta, where flooding and rivers shape everyday life, three-compartment houses and stilt houses open toward water, with high floors, generous verandas, and light materials that dry quickly after rain.

Modern Vietnam houses add further layers to this picture. Heritage buildings in old towns or city centers, such as colonial villas and merchant houses, stand next to simple rural homes made from brick, bamboo, and corrugated metal. At the same time, new smart or green houses experiment with large glass openings, planted facades, rooftop gardens, and energy-efficient systems. For foreign buyers or renters, the most familiar options are likely to be tube houses, standard apartments, serviced apartments, and villas in gated or planned communities, while traditional wooden houses are more often experienced through tourism or special conservation projects.

What "Vietnam house" means today

Traditional houses, modern homes, and heritage buildings

The term “Vietnam house” today can refer to both deeply traditional Vietnamese house design and very contemporary residential buildings. On one hand, it evokes images of shaded courtyards, red clay tiles, carved wooden beams, and family altars filled with incense. On the other hand, it can describe concrete high-rises, minimalist villas with wide glass walls, or compact city apartments equipped with modern appliances. For many families, daily life happens in a mix of these worlds: a concrete tube house with a small internal courtyard or garden, decorated with both modern furniture and inherited altars or wooden cabinets.

Traditional domestic houses in Vietnam come in several main forms. In the lowland north, courtyard houses usually have a U-shaped or three-part layout, with a main hall and two side buildings arranged around an open yard. Roofs are covered with curved clay tiles, and thick brick or mud walls keep interiors cool. In the central region, Ruong houses are refined wooden houses with steep tiled roofs, delicate carved beams, and panel walls that can be opened or closed for ventilation. In the south and Mekong Delta, three-compartment houses and stilt houses face rivers, with wide verandas and high floors to deal with humidity and floods. These domestic house types focus on climate comfort, family life, and ancestral worship, rather than monumental scale.

Modern Vietnam houses, in contrast, are often built in reinforced concrete and steel, with brick infill walls and tiled or metal roofs. Many are tube houses that rise three to six stories or more, stacking multiple generations, rental rooms, or small shops on one narrow plot. Others are apartments in multi-unit buildings that share staircases, lifts, and common facilities. Contemporary villas in new suburbs may have car garages, private gardens, and balconies, while still integrating local habits such as outdoor cooking areas, shrines, and spaces for extended family gatherings.

It is useful to separate these domestic houses from monumental or civic architecture, even though there are connections between them. Civic and cultural buildings such as temples, communal houses, opera houses, and government buildings use larger scales and more formal layouts, but they often borrow roof shapes, courtyards, and decorative patterns from traditional homes. Notable heritage houses that visitors can see include Tan Ky Old House in Hoi An, a well-preserved merchant home that mixes Vietnamese, Chinese, and Japanese features, and old family houses in Hue and other ancient towns. Iconic public buildings like the Hanoi Opera House Vietnam, built in the early 20th century, show French influence in their form and decoration, yet they stand within city districts still filled with typical Vietnam houses. Together, these layers create the architectural context for understanding what a Vietnam house means today.

Why many people search for "Vietnam House" restaurants and cafes

Online, many searches for “Vietnam house” do not point to architecture or housing at all, but instead to restaurants, cafes, or coffee houses that use this name in different countries. These venues often want to create a sense of Vietnamese home life, combining traditional food with interior elements such as bamboo furniture, lanterns, rattan lamps, and wall art showing old streets or riverside villages.

In contrast, articles that describe tube houses, stilt houses, or house prices are about Vietnamese homes and real estate. Understanding this difference makes it easier to filter search results and focus on the information you need, whether that is architectural inspiration, cultural context, or practical guidance on buying or renting a house in Vietnam.

Traditional Vietnamese house types and philosophies

Northern, central, and southern house typologies

Traditional Vietnamese houses vary strongly between the north, central coast, and south, because each region has different climate conditions, histories, and cultural influences. In the north, winters can be quite cold and damp, while summers are hot and humid, so houses need to protect residents from both heat and cold. Along the central coast, storms and typhoons bring heavy rain and high winds, demanding strong building frames and roofs. In the southern plains and the Mekong Delta, temperatures are warm year-round and heavy rains cause frequent flooding, so houses must stay cool and dry while living closely with water.

In northern Vietnam, especially in the Red River Delta, a common traditional form is the courtyard house. Typically, there is a main hall building facing south or southeast, with one or two side wings forming a U-shaped or three-part layout around an internal yard. Roofs are covered in clay tiles with slightly upturned edges, and walls are made of brick or earth. Thick walls, low eaves, and shaded verandas help regulate temperature. The main hall often holds the family altar and is used for ceremonies, while side buildings contain bedrooms and storage. Many rural families also have small outbuildings for cooking, livestock, or tools, arranged around ponds and gardens.

Central Vietnam has its own refined house type known as the Ruong house, found in provinces such as Thua Thien Hue and Quang Nam. Ruong houses use strong wooden frames with carefully joined columns and beams, often made from local hardwoods. Roofs are steeply pitched and covered with heavy tiles to resist wind. The floors may be raised above ground level to reduce moisture damage during storms or seasonal floods. Interior spaces are defined by wooden panel walls that can sometimes slide or open, creating flexible room arrangements. Rich carving on beams and columns shows symbols related to prosperity, longevity, and protection.

In southern Vietnam and the Mekong Delta, traditional three-compartment houses (often called “ba gian”) and stilt houses respond to a wetter, warmer environment. Three-compartment houses usually have a central hall flanked by two side rooms, with a long veranda at the front facing a garden or a river. They often sit on a raised plinth or low stilts to stay above floodwater. Stilt houses in riverine or coastal areas are built higher on wooden or concrete posts, allowing water to flow underneath during high tides or floods. These houses often use lightweight materials such as bamboo, timber, and thatch, and they prioritize ventilation, shade, and direct access to boats and waterways. Together, these regional house types show how traditional Vietnam houses are shaped by landscape, climate, and local ways of life.

Materials and climate-responsive construction

Traditional Vietnamese builders relied on materials that were locally available, affordable, and well suited to the tropical monsoon climate. Common materials included wood, bamboo, brick, thatch, and clay tiles. Hardwood species such as jackfruit, ironwood, or teak were used for main columns and beams because they are strong and durable. Bamboo, a fast-growing grass, was widely used for secondary structures, floors, walls, and roof framing. Bricks and compacted earth formed walls and foundations, while thatch from palm leaves or grasses covered roofs in simpler houses. Clay tiles, fired in local kilns, were used for more permanent roofs and helped shed heavy rain.

These material choices supported climate-responsive construction without modern air-conditioning. Open verandas, deep roof eaves, and shaded courtyards reduced direct sun on walls and windows, keeping indoor spaces cooler. High ceilings and roof vents allowed hot air to rise away from living areas, while gaps between boards, woven bamboo panels, and internal courtyards promoted cross-ventilation. In flood-prone areas, raised floors or stilt structures kept main living spaces above water, protecting belongings and bedding during the rainy season. Many of these passive design strategies are now studied as examples of sustainable, low-energy building practice.

Today, architects and homeowners in Vietnam are reinterpreting these traditional solutions using modern materials and construction techniques. Concrete slabs may replace timber floors, but are combined with open stairwells and internal light wells to maintain airflow. Instead of thatch, designers might use insulated metal roofs with wide overhangs to control heat and rain. Perforated brick screens, sometimes called “ventilation bricks,” provide shade and privacy while letting breezes pass through, echoing the role of bamboo or latticework in earlier houses. These approaches show how long-standing knowledge about climate and comfort continues to influence new Vietnam house design, linking heritage materials and forms with modern ideas about sustainability.

Ruong houses and famous old homes in Vietnam

Ruong houses are among the most distinctive traditional houses in central Vietnam. They are known for their elegant wooden frames, modular layout, and detailed decorative carving. The frame is built from vertical columns and horizontal beams connected by wooden joints rather than metal nails. This structure carries the weight of the roof, so walls can be made from lighter panels that may be opened or removed for air and light. The roof typically has several layers of clay tiles and a pronounced pitch, helping rainwater drain quickly during storms.

Inside a Ruong house, spaces are often arranged in bays defined by column lines, with the central area reserved for ancestor worship and receiving guests. Carved motifs on beams and brackets may feature flowers, mythical animals, or calligraphic symbols, reflecting the owner’s status and beliefs. Some Ruong houses stand alone within gardens, while others form part of small village clusters. Their construction requires specialized carpentry skills that are now being preserved by craftspeople and conservation projects.

Vietnam also has many famous old houses that help visitors understand how wealthy families, merchants, and officials once lived. Tan Ky Old House in Hoi An is a well-known example. Built by a merchant family, it combines a Vietnamese tube-house layout, Chinese woodwork, and Japanese-influenced structural details. Narrow at the street, it extends deep into the block with courtyards that bring in light. The interior includes dark polished timber, carved screens, and areas for storing goods. Other preserved houses in Hoi An’s Ancient Town and in Hue’s garden houses show similar mixtures of local and foreign influences.

Visitors, students, and professionals can experience these heritage houses in different ways. Some operate as museums where guided tours explain architectural features and family histories. Others continue to function as private homes that open certain rooms to the public during the day. In central provinces, small villages still have clusters of Ruong houses where researchers and architecture students can observe traditional joinery and layout in a living context. For anyone interested in Vietnam house culture, seeing these old homes in person provides valuable insight into spatial organization, social customs, and long-term adaptation to climate and environment.

Feng shui (phong thủy) basics in Vietnamese house design

Feng shui, known in Vietnamese as phong thủy, plays an important role in how many families choose and arrange their houses. The basic idea of feng shui is that the placement and orientation of buildings and rooms should harmonize with natural forces to support health, prosperity, and emotional balance. In practice, this often means considering the direction a Vietnam house faces, where to put the main entrance, and how to place important elements such as the family altar, kitchen, and beds.

A common preference is for houses to face roughly south or southeast, especially in the north of Vietnam. This orientation allows cool breezes to enter while avoiding cold winter winds from the north. Many people also prefer to avoid sharp corners from neighboring buildings pointing directly at their front door, a situation believed to send negative energy toward the house. Internally, altars are usually placed against a solid wall in a respectful and visible position, but not directly facing bathrooms or cluttered areas. Kitchens are often located in positions thought to support good fortune while reducing the spread of smoke and heat within the house.

Feng shui concepts are usually balanced with practical needs in both traditional and modern Vietnam houses. For example, a family may consult a feng shui expert to choose the best room for the altar but still prioritize safety, daylight, and easier access for elderly relatives. In small tube houses or apartments, it is not always possible to meet every ideal condition, so people adapt by using screens, plants, or furniture placement to adjust the flow of space. Some developers of new housing projects also consider general feng shui principles in street layouts and building orientations, while still following technical planning standards and regulations.

It is important to remember that feng shui practices vary between families, regions, and generations, and they are not rigid rules that everyone follows in the same way. Some people focus strongly on birth charts and direction systems, while others treat feng shui more as a cultural tradition that supports good design choices like ventilation, natural light, and organized layouts. For international readers, it can be helpful to view feng shui as one of several lenses that shape Vietnamese house design, alongside climate, budget, and building codes.

Contemporary Vietnam house design and interiors

Vernacular principles in modern Vietnamese homes

Modern architects in Vietnam often look to vernacular, or traditional local, principles when designing new houses. Instead of copying old forms exactly, they reinterpret elements like courtyards, verandas, and shading devices in concrete and glass structures. This approach helps create comfortable, energy-efficient homes that still feel connected to Vietnamese culture and landscape. For example, a new urban house may include a small internal garden or a double-height void that functions like a courtyard, bringing light and air into the middle of a deep plot.

Cross-ventilation is a key principle that remains central in many new Vietnam house projects. By arranging windows, doors, and openings on opposite sides of rooms or around vertical shafts, architects allow breezes to flow through the building, reducing reliance on mechanical cooling. Large sliding doors to balconies or terraces make indoor-outdoor spaces flexible, so families can open up the house in cooler seasons and close it during heavy rain. Shading elements such as brise-soleil (fixed sun shades), perforated brick screens, or dense planting on balconies protect interiors from direct sun while still letting in diffused light.

These vernacular-inspired strategies offer clear benefits. Better natural ventilation and shade lower energy use and electricity bills. Courtyards and planted voids provide privacy from busy streets while still creating calm, green views for residents. Layered facades with screens or louvers reduce noise and dust, improving health and comfort. Many houses also integrate local materials and craft techniques, such as handmade tiles, traditional bricks, or bamboo details, in a contemporary way that respects both artisans and modern lifestyles.

Examples of such contemporary Vietnam houses include urban homes that wrap several small gardens around staircases, or suburban villas that use wide overhangs and open ground floors inspired by stilt houses. While each project is unique, the common theme is a careful balance between tradition and innovation, drawing on vernacular principles not for nostalgia, but to create practical, livable spaces in today’s cities and towns.

Tube houses and solutions for narrow urban plots

The tube house is one of the most recognizable Vietnam house types in cities. It is characterized by a very narrow frontage, sometimes only three to five meters wide, and a deep plan that can extend 20 meters or more. This shape emerged historically from land taxation and subdivision patterns, where street-facing width was limited and taxes were based on frontage. As cities grew denser, families added new floors on top, turning single-story houses into tall, multi-level homes.

Tube houses present several design challenges. Because they are so narrow and usually attached to neighboring houses on both sides, natural light and fresh air can only easily enter from the front and back. The front often faces a busy street, exposing living rooms and bedrooms to traffic noise and pollution. Long corridors or dark interiors are common if no additional openings are created, and staircases can feel cramped if not carefully planned. Despite these difficulties, tube houses are extremely common and house millions of people, including families, students, and remote workers renting individual rooms.

Architects and builders use a range of solutions to improve tube house living conditions. Internal courtyards or light wells cut into the plan bring daylight and ventilation down through the building. Skylights over staircases or central voids help distribute light to lower floors. Split-level arrangements, where floors are staggered rather than flat, reduce the feeling of narrowness and create visual connections between spaces. Many tube houses also include rooftop terraces or gardens that serve as outdoor living rooms, laundry areas, and places to grow plants.

Compared with traditional single-story houses spread across wider plots, tall tube houses change how families experience space. Vertical circulation becomes a bigger part of daily life, as residents climb stairs many times a day. Ground-floor spaces often mix commercial and residential uses, such as a shop, cafe, or office under upper-floor bedrooms. For students and digital nomads, renting a room in a tube house can be affordable and central, but it is important to check ventilation, noise, and access to shared kitchens or bathrooms. Well-designed tube houses show that, even on narrow plots, creative planning can produce comfortable Vietnam houses that respond to urban realities.

Green and sustainable Vietnam house examples

As energy costs rise and awareness of climate change grows, green and sustainable features are becoming more common in new Vietnam houses. Many designers aim to reduce dependence on air conditioning and artificial lighting by using plants, shading, and natural airflow. A simple example is a house with balconies full of potted trees or climbing vines, which cool the facade and filter dust. Another example is the use of double-skin facades, where an outer layer of perforated bricks or screens shades windows behind, lowering indoor temperatures.

In some innovative houses, entire facades are covered in planters, creating a vertical garden that improves insulation and provides privacy from the street. Courtyards and roof openings are oriented to capture prevailing breezes while being protected from harsh sun and heavy rain. High-level vents and operable windows let hot air escape at night, helping cool down interiors without mechanical systems. These strategies build on traditional knowledge about verandas, eaves, and cross-ventilation but combine them with new forms and materials.

Sustainable Vietnam houses may also experiment with resource management. Rainwater collection systems can supply water for irrigation and some household uses, reducing pressure on municipal supplies. Recycled materials, such as reclaimed timber, reused bricks, or upcycled metal elements, lower the environmental impact of construction. In some higher-budget projects, solar panels on roofs generate electricity, especially in sunny southern regions, offsetting part of the home’s energy demand.

These features often increase initial construction costs because they require careful design, higher-quality materials, or additional equipment. However, they can reduce long-term operating expenses by lowering electricity and water bills, while also improving comfort and resilience during power cuts or heatwaves. For homeowners and designers, the combination of traditional passive cooling strategies and modern green technologies is shaping a new generation of Vietnam houses that respond both to local climate and global sustainability goals.

Interior styles, Mekong Delta influence, and handicrafts

Interior design in Vietnam houses reflects a wide range of styles, from very minimal to richly traditional. In many new urban homes, especially apartments and townhouses, minimalist interiors with white walls, polished concrete or light wood floors, and simple built-in furniture are popular. This style suits compact spaces and makes rooms feel larger and brighter. At the same time, many families still prefer warm wooden interiors with carved furniture, display cabinets for porcelain and family photos, and decorative motifs inspired by historical houses.

The Mekong Delta and southern culture influence interior layouts and furniture choices that emphasize relaxation and open-plan living. Houses often have large living-dining spaces that connect directly to verandas or terraces, allowing family members to move easily between indoor and outdoor areas. Hammocks are common in southern homes, hung in living rooms or on porches for resting during hot afternoons. In riverside houses, windows and seating areas often face the water, making the river a central visual and social element of the home.

Vietnamese handicrafts play an important role in decorating interiors across the country. Bamboo furniture, such as chairs, stools, and bed frames, is lightweight and durable. Rattan lamps and woven baskets add texture and diffuse light gently. Ceramic vases, bowls, and tiles from craft villages bring color and traditional patterns into modern spaces. Woven textiles, including blankets, cushions, and wall hangings from ethnic minority communities, introduce regional identity and craftsmanship.

For renters, students, or short-term visitors, these craft items offer an easy way to bring a sense of Vietnam house culture into a temporary home without major renovations. A simple combination of a bamboo lamp, a small altar shelf, ceramic tableware, and a woven mat can transform a standard apartment or guesthouse room. Because these items are usually portable and not fixed to the building, they fit well with flexible living situations and can be taken along when moving to a new place.

French colonial legacy and modern Vietnam house identity

French colonial architecture has left a visible mark on many Vietnamese cities, especially Hanoi, Hue, and Ho Chi Minh City. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, French planners and architects introduced new building types, construction methods, and decorative styles. Villas with balconies, shutters, and tall windows appeared alongside traditional houses, as did wide tree-lined boulevards and public squares. Many of these colonial-era buildings combined European forms with local adaptations to climate, such as high ceilings and cross-ventilation.

Iconic sites like the Hanoi Opera House Vietnam, inspired by French opera houses, illustrate this period’s architectural ambitions. Built with masonry and stone, its grand facade and interior details differ from typical domestic Vietnam houses, yet it stands in a district of villas and shophouses that also mix French and local features. In cities like Hue and Da Lat, historic villas with tiled roofs, elegant staircases, and decorative ironwork still survive, some converted into offices, hotels, or cultural venues. More playful structures such as the Crazy House in Da Lat, created much later, show how imaginative forms can become tourist attractions within the broader landscape of Vietnamese housing and architecture.

Today, modern Vietnam house design often blends influences from colonial, traditional, and international modern styles into a distinct identity. A contemporary villa might have simple geometric volumes and large glass doors, yet still use tiled roofs or shutters reminiscent of older buildings. Tube houses may feature French-style balconies on the front facade, while their interior organization follows local patterns of multi-generational living and mixed residential-commercial use. Apartments in new developments sometimes reference colonial aesthetics in lobby design or facade colors, even as they provide modern amenities.

It is important to acknowledge that colonial history involved complex and painful aspects of foreign rule. However, in architectural terms, many Vietnamese architects and residents have adapted and transformed colonial-era forms to fit local needs and tastes. The result is a layered urban fabric where traditional wooden houses, colonial villas, socialist-era blocks, and contemporary towers coexist. This mix shapes the visual character of Vietnamese cities and contributes to the evolving identity of the Vietnam house in the 21st century.

Vietnam house prices, buying, and renting

Overview of Vietnam’s housing market

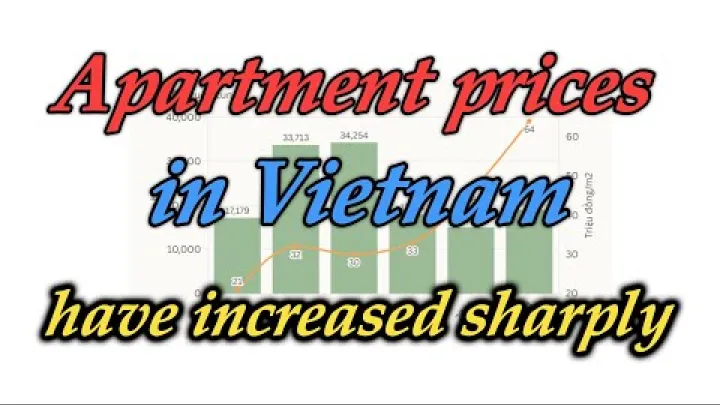

Vietnam’s housing market has been shaped by rapid urbanization, strong economic growth, and demographic changes over the past few decades. As more people move from rural areas to cities for work and education, demand for apartments and houses in major urban centers has increased. New high-rise apartment projects and planned suburban areas have spread around Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, while provincial cities such as Da Nang, Hai Phong, Nha Trang, and Can Tho are emerging as secondary markets with growing housing demand.

The market can be broadly divided into several segments. Primary markets in large cities focus on new apartments, serviced residences, and townhouses developed by national and international firms. Secondary cities offer a mix of smaller apartment projects, individual houses, and land plots, often at lower prices but with varying infrastructure quality. Rural and provincial areas still rely heavily on self-built houses on family land, where formal real estate development is less intense and prices are significantly lower. Within each city, there are large differences between central districts, established residential areas, and new fringe developments.

Factors that influence Vietnam house prices include location, land use rules, infrastructure, and local amenities. Houses and apartments near good schools, large office districts, modern shopping centers, and reliable public transport usually command higher prices. Projects with clear legal status, completed infrastructure, and reputable developers are also valued more highly than properties with unclear land titles or unfinished roads and utilities. In some areas, increased foreign interest and investment have contributed to price growth, especially in popular urban districts and coastal cities.

Because market conditions can change quickly due to policy adjustments, credit availability, and economic trends, it is important to approach any price information as approximate and time-sensitive. Even within the same district, two streets can have very different price levels depending on street width, allowed building heights, and neighborhood reputation. For anyone considering buying or renting, checking current local listings and speaking with knowledgeable local contacts or professionals is essential to understand the real situation at a specific time and place.

Typical house and apartment prices in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City

In these major cities, apartments in mid-range projects often fall within a broad band that, when converted to US dollars, might be somewhere between the low to mid thousands per square meter, while premium or luxury projects can reach higher levels. Landed houses, including tube houses and townhouses in central districts, frequently cost significantly more overall because buyers pay for both the land and the building, and central land is limited.

Prices differ not only between the two cities but also between central and outer districts. In general, Ho Chi Minh City has historically shown slightly higher apartment prices in some central and eastern districts due to strong investor interest and rapid development, while Hanoi has strong demand in its inner districts and in certain new urban areas on the western side. Suburban districts in both cities offer lower entry prices but may require longer commutes and have less complete public transport and services.

| Hanoi (approximate patterns) | Ho Chi Minh City (approximate patterns) | |

|---|---|---|

| Apartments in central or popular districts | Higher price range per square meter; strong demand from local buyers and investors | Comparable or sometimes higher ranges; many new projects attracting both local and foreign buyers |

| Apartments in outer or new suburban districts | Lower prices; developing infrastructure; more supply of larger units | Lower to mid-range prices; some areas expected to grow with new transport links |

| Landed houses in central districts | Very high total prices due to limited land and strong commercial potential | Also very high; street-front tube houses often valued for business use |

Project quality, legal status, and nearby transport or schools all influence where a specific property falls within these broad ranges. Apartments in projects with complete legal documentation, reliable maintenance, and good community facilities tend to maintain value better than units in poorly managed or uncertain projects. For landed houses, width of street access, ability to park cars, and zoning rules for commercial use can dramatically affect price. Because actual numbers shift with the market, prospective buyers and renters should use these patterns as general guidance and then verify up-to-date figures through current listings and professional advice.

It is also important to remember that prices in secondary cities and provincial towns can be significantly lower than in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City. For people who can work remotely or prefer a quieter lifestyle, cities like Da Nang or Nha Trang may offer more space for the same budget, though with different job markets and community structures. Evaluating total living costs, not just the purchase or rental price of the house, provides a clearer picture when choosing where to live.

Can foreigners buy a house in Vietnam? Rules and limits

Foreigners can buy certain types of residential property in Vietnam, but there are clear rules and limits that differ from those for Vietnamese citizens. The legal framework allows foreign individuals and organizations to purchase apartments and some landed houses in approved commercial housing projects. However, foreign buyers generally do not own the land itself in a freehold sense. Instead, they receive a form of long-term use right or lease for a defined period.

One key feature of the system is the ownership term, which is commonly up to 50 years for foreign individuals, with the possibility of extension under certain conditions and subject to current regulations. There are also quotas that limit how many units in a given building or area can be owned by foreigners. For example, foreign ownership is often capped at around 30 percent of the units in each apartment building and a fixed number of landed houses (such as villas or townhouses) in each administrative area equivalent to a ward. These rules aim to balance foreign participation with local housing needs.

Additionally, foreigners are not allowed to buy properties in areas classified as sensitive for national defense or security. Some coastal or border regions, as well as zones near military installations, may have special restrictions. Projects that wish to sell to foreigners must be approved by the authorities, and not every development automatically qualifies. This means that when a foreign buyer sees a Vietnam house for sale advertised in English, it is important to confirm that the specific project or property is legally open to foreign ownership.

Because regulations can be adjusted over time and interpretation may vary between localities, anyone seriously considering buying a house in Vietnam should consult local lawyers or licensed real estate agencies who are familiar with the latest rules. They can explain allowed ownership structures in plain language, help verify whether a property is in an approved project, and ensure that contracts reflect the correct legal terms. This professional guidance is especially important for foreign buyers who are not fluent in Vietnamese and may not be familiar with local legal terminology and procedures.

House for sale in Vietnam: what buyers should know

Buying a house for sale in Vietnam involves several steps that are similar to other countries but with some local specificities. Whether you are a domestic or foreign buyer, it is important to approach the process systematically to manage risks and avoid misunderstandings. Beyond price negotiation, the most important tasks are checking legal documents, understanding the property’s status, and arranging secure payment and transfer of rights.

A typical purchase process can be organized into the following steps:

- Property search and shortlisting: Identify neighborhoods that match your lifestyle and budget, then shortlist specific houses or apartments. Consider factors such as access to work or school, public transport, flooding risk, and local services.

- Legal and technical due diligence: Check key documents, including the land use right certificate and house ownership certificate (if separate), building permits for any extensions, and any co-ownership or project rules. Inspect the physical condition of the building, focusing on structure, waterproofing, and services.

- Price negotiation and preliminary agreement: Once you are satisfied with the property, negotiate price and basic terms such as deposit amount, payment schedule, and items included (for example, built-in furniture or fixtures). These can be recorded in a reservation or preliminary agreement.

- Contract signing and payment: Sign the official sale and purchase contract, usually before a notary or authorized officer, and follow the agreed payment schedule. For foreigners, this may include showing valid passport and visa documents and proof that the project is open to foreign buyers.

- Registration and handover: After full payment, complete registration procedures with relevant authorities so that your ownership or use right is properly recorded. Arrange for handover of keys, meters, and management fees if the property is in an apartment building or gated community.

Important checks for buyers include verifying that there are no disputes or mortgages registered against the property, confirming that the land use purpose matches residential use, and reviewing the reputation and track record of the project developer if buying from a new development. For older houses, it is wise to ask about any planned road widening or redevelopment projects that might affect the site in the future.

Foreign buyers may face additional challenges such as language barriers, unfamiliar documentation formats, and limited local credit options. Many banks require stronger collateral or higher down payments from foreign borrowers, and mortgage products can differ from those in other countries. Working with trusted interpreters, lawyers, or licensed agents can help bridge information gaps and ensure that each step is understood. While professional services add to transaction costs, they are a valuable tool for risk management in an unfamiliar legal and cultural environment.

Vietnam house rental and house for rent in Vietnam: key points

For many international students, remote workers, and short-term residents, renting a house in Vietnam is more practical than buying. The rental market offers a wide range of options, from simple rooms in shared houses to fully serviced apartments and entire villas. Understanding the main rental types and typical terms will help you choose housing that fits your budget and lifestyle.

The main rental options include:

- Serviced apartments: Units with furniture, cleaning, and sometimes reception services included, popular in central city areas.

- Standard apartments: Unfurnished or partially furnished units in residential buildings, where tenants arrange their own utilities and services.

- Shared houses: Rooms rented within a larger Vietnam house, often a tube house, with shared kitchen and bathroom facilities, common among students and young workers.

- Whole houses or villas: Complete houses rented to a single tenant or family, sometimes in gated compounds or suburban neighborhoods.

- Short-term rentals: Rooms, studios, or houses booked on a weekly or monthly basis, often through online platforms.

Rental prices vary widely by city, district, and property type. In major cities such as Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, a basic room or small apartment in an outer district can be relatively affordable, while a well-located serviced apartment or villa in central or popular expatriate areas can cost several times more. In smaller cities and provincial towns, average rents for both apartments and houses are usually significantly lower. When comparing options, remember to include costs for electricity, water, internet, and building management fees, as these are often not included in the base rent.

Lease terms are usually set for 6 or 12 months, with the possibility of extension. Landlords commonly request a deposit, often equivalent to one or two months’ rent, which is refundable if there is no damage and notice requirements are respected. It is important to have a written agreement, even for room rentals, stating the rent, deposit, duration, payment method, and responsibilities for repairs and utilities. International renters may deal directly with landlords or through agencies that can assist with translation and negotiation.

Students and digital nomads should pay attention to internet speed, noise levels, and flexibility of lease terms. Families relocating for work may focus more on proximity to schools, playgrounds, and healthcare. In all cases, visiting the property in person, asking neighbors about the area, and checking access at night and during rain are practical steps. Keeping terminology simple and clarifying each clause in the lease can prevent misunderstandings later, especially when contracts are bilingual or when parties have different legal backgrounds.

Smart and green Vietnam house trends

Smart home technology adoption in Vietnam

Smart home technology is gradually becoming part of the Vietnam house landscape, especially in new urban apartments and higher-end houses. Many developments now offer optional packages that allow residents to control lighting, air conditioning, and security systems through smartphone apps or voice commands. Common features include smart door locks, video doorbells, motion sensors, and programmable lighting scenes that can be adjusted remotely.

In new apartment projects, smart systems are often pre-installed in living rooms and main bedrooms, while additional devices can be added later. In landed houses and villas, homeowners may choose custom systems that integrate gate control, garden lighting, and CCTV cameras. These technologies can improve comfort by allowing residents to cool or light spaces before they arrive home, and they can enhance security with real-time notifications and remote monitoring.

However, smart home adoption in Vietnam also faces challenges. Internet reliability and coverage can vary between neighborhoods and providers, and some systems depend heavily on stable connections. Concerns about privacy and data security are growing, especially when devices are connected to external servers. There is also price sensitivity: many buyers and renters prioritize location and basic finishes over advanced technology, so smart features are often treated as optional upgrades rather than standard equipment.

Despite these issues, interest in smart Vietnam houses is likely to increase as device costs fall and integration becomes easier. Simple, modular solutions that can be installed in existing tube houses and apartments without major rewiring are particularly attractive. For international residents, compatibility with global platforms and clear user interfaces in multiple languages can be deciding factors when choosing smart systems. Over time, the combination of smart control and passive climate design may play an important role in making Vietnamese homes both more efficient and more comfortable.

Construction costs and how they affect new houses

When planning to build a new Vietnam house, it is important to distinguish between land cost and construction cost. In many urban areas, the land itself represents the larger share of total investment, especially on central streets where commercial potential is high. In suburban and rural areas, by contrast, land may be relatively affordable, and the main budgeting focus shifts to building materials, labor, and design.

Construction costs depend on several factors, including house size, number of floors, structural system, and interior finish level. Basic concrete-and-brick houses with simple finishes and limited custom details generally cost less per square meter than designs with complex forms, high-quality imported materials, or extensive glass facades. Labor costs in Vietnam are still lower than in many developed countries, but they are rising, and skilled carpentry, stonework, or custom metalwork add to the budget.

Adding sustainability features can influence both upfront and long-term costs. For example, designing deep eaves, cross-ventilation, and efficient orientation may not increase construction cost significantly but can reduce energy bills. Installing solar panels, high-performance glazing, or advanced insulation increases initial spending but may pay back over time through reduced electricity use. Rainwater collection systems, greywater reuse, and green roofs also require higher planning and construction quality but support resilience and environmental performance.

Smart home technology, premium appliances, and high-end finishes such as imported tiles or custom built-in furniture further raise construction costs. For foreign investors and long-term residents, it is useful to consider not only the headline construction budget but also maintenance, energy consumption, and possible future upgrades. Working with architects, engineers, and contractors who understand both local conditions and modern building expectations can help balance cost, durability, and comfort in a new Vietnam house.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the main types of traditional houses in Vietnam?

The main types of traditional houses in Vietnam include northern courtyard houses, central Ruong houses, and southern three-compartment (ba gian) houses. Mountain ethnic groups also have stilt houses adapted to floods and terrain. Each type reflects local climate, materials, and cultural traditions. Many modern Vietnamese homes reinterpret these forms with new materials.

How much does a typical house cost in Vietnam?

A typical apartment in major cities like Hanoi or Ho Chi Minh City often ranges from about 2,500 to 3,500 USD per square meter, with luxury projects costing more. Small landed houses in urban areas can easily exceed 200,000 to 300,000 USD depending on location and land size. Prices in secondary cities and provinces are usually much lower. Always check current local listings because market conditions change over time.

Can foreigners buy and own a house in Vietnam?

Foreigners can buy and own apartments and some landed houses in approved commercial housing projects in Vietnam under specific quotas. Foreign ownership is generally capped at 30% of units in each apartment building and about 250 landed houses per ward-equivalent area. Ownership is normally granted as a 50-year lease, with possible extension subject to regulations. Foreigners cannot buy in areas considered sensitive for national defense or security.

What is special about Vietnamese tube house architecture?

Vietnamese tube houses have very narrow frontages and deep plots, a form shaped by historical land tax rules and dense urban fabric. Architects solve light and ventilation problems using internal courtyards, atriums, skylights, and greenery. Modern tube houses often stack multiple floors and use split levels to maximize space. This type is the most common urban Vietnam house form in many cities.

What materials are commonly used in traditional Vietnamese houses?

Traditional Vietnamese houses typically use local materials such as wood, bamboo, bricks, and thatch from palm leaves or grasses. In rural areas, woven bamboo walls and thatched roofs create flexible, breathable structures suited to tropical storms. In more permanent houses, hardwood like jackfruit or ironwood is used for columns and beams, with clay tiles on roofs. These materials keep houses cool, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly.

Is renting a house in Vietnam expensive compared to apartments?

Renting a whole house in Vietnam is usually more expensive than renting an apartment in the same district, because houses provide more space and land. In big cities, a basic apartment might cost a few hundred US dollars per month, while a comfortable house can range from several hundred to over a thousand US dollars depending on size and location. In smaller cities and towns, both house and apartment rents are significantly lower. Sharing a house with other tenants can reduce individual costs.

How does feng shui influence Vietnamese house design and layout?

Feng shui (phong thủy) influences Vietnamese house orientation, room placement, and interior arrangement to align with beneficial directions and natural forces. Many homes are oriented to the south to catch cooling breezes and avoid cold northern winds. Altars, entrances, kitchens, and bedrooms are often positioned according to birth-based direction systems. When applied thoughtfully, feng shui principles support good light, ventilation, and psychological comfort.

What are some examples of famous historical houses in Vietnam?

Famous historical houses in Vietnam include Tan Ky Old House in Hoi An, Ruong houses in Loc Yen Village (Quang Nam), and Cai Cuong Ancient House in Vinh Long. These homes showcase refined wooden structures, carved details, and mixed Vietnamese, Chinese, and French influences. Many ancient houses in Hoi An are still occupied by families while operating as living museums. Visiting them offers insight into traditional Vietnam house culture.

Conclusion and next steps

Key takeaways about Vietnam house design and living

Vietnam houses range from traditional courtyard, Ruong, and stilt houses to narrow urban tube houses, apartments, and modern villas, each shaped by climate, culture, and patterns of urban growth. Across these types, common themes include attention to natural ventilation, shade, and flexible spaces that support multi-generational families and social life. Contemporary designs increasingly combine vernacular principles, colonial legacies, and global modernism to form a distinct Vietnam house identity that is both local and cosmopolitan.

Understanding local house types and design principles helps travelers, students, renters, and potential buyers choose locations and housing forms that suit their needs. Knowledge of climate-responsive design, feng shui preferences, and regional differences in materials and layouts also enriches appreciation of Vietnamese daily life. Looking ahead, green design, smart home technology, and evolving market rules will continue to shape how Vietnam houses are built, lived in, and valued, both by local residents and by an international audience.

Practical next steps for buyers, renters, and learners

Readers interested in living in a Vietnam house can use the information in this guide to narrow down preferred regions, house types, and budget levels. Comparing the characteristics of tube houses, apartments, and suburban homes against personal priorities such as commute time, noise tolerance, and access to green space provides a useful starting point. Those considering property purchase should take particular care with legal checks, including project eligibility for foreign ownership where relevant, and should expect regulations and prices to evolve over time.

For renters and shorter-term residents, visiting several neighborhoods, talking with current residents, and reviewing lease terms closely can lead to more comfortable and predictable housing experiences. Students, architects, and curious travelers may wish to explore both well-known heritage houses and contemporary experimental projects to deepen their understanding of Vietnamese housing culture. Even as specific figures and regulations change, a focus on climate-responsive design, clear documentation, and respect for local customs will remain valuable when engaging with any Vietnam house.

Your Nearby Location

Your Favorite

Post content

All posting is Free of charge and registration is Not required.

![Preview image for the video "[Story] - The northern traditional house of Vietnam". Preview image for the video "[Story] - The northern traditional house of Vietnam".](/sites/default/files/styles/media_720x405/public/oembed_thumbnails/2025-12/7zPfbnRB3eRWIzPVxSWUVvEjTE3YS8FL3FfiV0yhySA.jpg.webp?itok=kMmqdHX1)