Vietnam Pho: History, Styles, Recipes, and Cultural Meaning

Vietnam pho is one of the most recognizable noodle soups in the world, yet many people only know it as “that tasty beef soup with herbs.” Behind each bowl is a long story of migration, colonial history, regional taste, and family tradition. For travelers, international students, and remote workers, learning about Vietnam pho is a simple way to connect with local culture. This guide explains what pho is, how it developed, the main regional styles, how to cook it at home, and how to order and enjoy it with confidence anywhere in the world.

Introduction to Vietnam Pho for Global Diners

Why Vietnam pho matters to travelers, students, and remote workers

When you move to a new country or travel for a long time, food can feel unfamiliar and even stressful. Vietnam pho offers a gentle and welcoming entry point into Vietnamese food culture because it is both comforting and easy to understand: a hot bowl of rice noodles, aromatic broth, and fresh herbs.

Another reason Vietnam pho matters globally is its availability. Pho shops now exist in cities across North America, Europe, Australia, and many parts of Asia, so you can usually find Vietnam pho soup even far from Vietnam itself. Because the dish is usually served with options for toppings, herbs, and condiments, it can fit many personal tastes and dietary needs. In this article, you will see pho not only as a delicious meal but also as a window into daily life, history, and identity in Vietnam.

Overview of what this Vietnam pho guide will cover

To help you navigate the world of pho Vietnam food, this guide is organized into clear sections that you can read in order or skim as needed. First, it defines what Vietnam pho is and what you can expect in a typical bowl. Then it looks at the origins of pho in northern Vietnam and the historical influences that helped shape it. This background will make later sections about regional styles and recipes easier to understand.

After the history, the guide explains the difference between northern and southern Vietnam pho, from broth flavor to noodles and garnishes. It then details the key ingredients and preparation techniques, followed by two practical Vietnam pho recipe sections: a home-style beef pho and a simple vegetarian Vietnam pho recipe. Later sections focus on cultural meaning, health and nutrition, and how to order and eat pho with confidence, including how to read a typical Vietnam pho menu. A dedicated Frequently Asked Questions section at the end answers common queries such as “is pho Vietnam or Thai,” “is pho healthy,” and how long to cook pho broth.

What Is Vietnam Pho?

Simple definition of pho

Vietnam pho is a Vietnamese rice noodle soup made with a clear, aromatic broth, flat rice noodles, and meat, most often beef or chicken.

In a typical bowl of Vietnam pho soup, hot broth is poured over cooked rice noodles and thinly sliced meat, then topped with herbs and onion. On the side, you usually receive lime, chili, and sometimes bean sprouts and sauces so that you can adjust the flavor to your own taste. This basic structure remains the same across regions, even though seasonings and toppings can differ.

Core components of a traditional pho bowl

Understanding the main components of a pho bowl helps you compare different versions and order with confidence. Each part plays a specific role in taste, texture, and aroma. The broth brings depth and warmth, the noodles provide body and comfort, the protein adds richness and nutrition, and the fresh herbs contribute brightness and fragrance.

Most traditional Vietnam pho bowls include the following elements:

- Broth: Long-simmered from beef or chicken bones with charred onion, ginger, and whole spices such as star anise, cinnamon, cloves, and black cardamom. It should taste clean yet complex.

- Rice noodles (banh pho): Flat, white noodles made from rice flour. They are soft but slightly chewy, forming the base of pho Vietnam food.

- Protein: Slices of beef or chicken, or other cuts like brisket, flank, tendon, tripe, or meatballs. In Vietnamese, you might see tai (rare steak), chin (well-cooked brisket), or bo vien (meatballs).

- Herbs and garnishes: Spring onion, cilantro, and sometimes sawtooth herb in the bowl. In many southern-style shops you also get Thai basil, bean sprouts, lime wedges, and fresh chili on a side plate.

- Condiments: Fish sauce, hoisin sauce, and chili sauce are common. Fish sauce adds salt and depth, while hoisin and chili bring sweetness and heat. These condiments allow you to personalize your Vietnam pho soup while keeping the broth’s character.

Is pho originally from Vietnam?

Yes, pho is originally from Vietnam, specifically from the northern part of the country. Most historians and food writers link the birth of pho to areas such as Nam Dinh province and the capital city Hanoi in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Questions like “is pho Vietnam or Thai” often appear because both Vietnam and Thailand are famous for noodle soups, but pho itself is firmly Vietnamese. While its development was influenced by French colonial beef culture and Chinese noodle traditions, the final dish, with its fish sauce seasoning and characteristic herbs, reflects Vietnamese tastes and local ingredients. Over time, pho spread from the north to central and southern Vietnam and, through migration, to the rest of the world.

Origins and Historical Development of Pho

Emergence of pho in northern Vietnam

The story of Vietnam pho begins in the Red River Delta of northern Vietnam, in a time of social and economic change. Around the late 1800s and early 1900s, the region saw growing urban centers and a rising working class that needed quick, filling, and affordable meals. Street vendors responded by creating simple noodle soups that could be eaten early in the morning or late at night, and from this environment, pho is believed to have emerged.

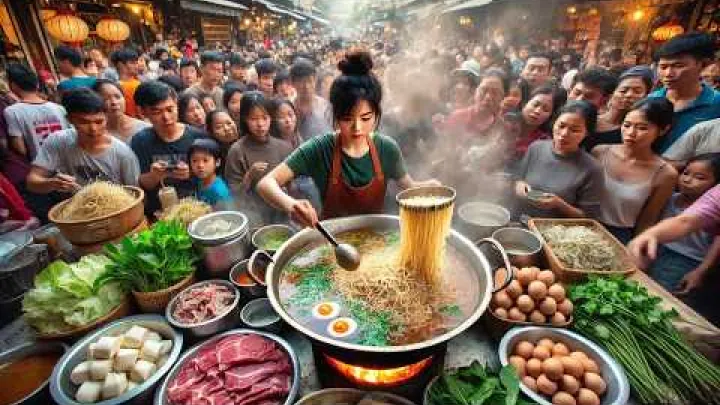

Nam Dinh, a province with strong textile and trading activity, and Hanoi, the colonial capital, are often mentioned as early centers of pho. Many early pho sellers walked the streets carrying poles with baskets at each end: one side with a pot of hot broth over a small charcoal fire, and the other with noodles, herbs, and bowls. Customers would sit on low stools at the roadside to enjoy a hot bowl before going to work. Over time, these mobile stalls grew into fixed stands and small shops, but the idea of pho as an everyday street food for ordinary people has remained central to its identity.

French colonial influence and beef culture

French colonial rule in Vietnam changed local eating habits in many ways, especially through the introduction of a stronger beef culture. Before this period, cattle in Vietnam were mainly used for labor rather than meat, and beef consumption was relatively limited compared with pork or fish. As French residents and soldiers developed a demand for steaks and roasts, slaughterhouses produced more beef, leaving behind bones and less popular cuts.

Vietnamese cooks made creative use of these leftover bones and trimmings by simmering them for hours with onion, ginger, and spices to create rich, clear broths. Some food historians note similarities between the French dish pot-au-feu, a slow-cooked beef and vegetable stew, and the idea of long-simmered beef broth, and even suggest that the name “pho” may be related to “feu.” However, influence does not mean that pho is French. Over time, Vietnam pho soup developed its own seasoning patterns, including fish sauce and local herbs, and became a distinct Vietnamese dish that reflects local climate, produce, and taste.

Chinese culinary contributions to pho

Chinese communities in northern Vietnam also played an important role in shaping pho, especially through noodle-making skills and spice use. Flat rice noodles and wheat noodles were already common in Chinese-influenced cooking, and many Chinese-run stalls in Vietnam sold various kinds of noodle soups. Techniques such as making rice noodles in different widths and simmering bone broths with whole spices existed in the region long before pho became famous.

What makes Vietnam pho unique is how it combines these Chinese techniques with specifically Vietnamese flavors. Instead of soy sauce as the main salty element, pho relies heavily on fish sauce. The herb profile also differs: sawtooth herb, Thai basil, and generous fresh lime are more characteristic of Vietnamese taste. In this sense, pho can be seen as a conversation between Chinese noodle traditions, French beef culture, and Vietnamese creativity, resulting in a dish that clearly belongs to Vietnam while acknowledging regional culinary exchange.

Regional Styles: Northern vs. Southern Pho

Key features of northern (Hanoi) pho

Northern pho, often associated with Hanoi, is known for its subtlety and focus on the natural flavor of beef and bones. The broth is usually very clear, with a light golden color and a strong yet clean beef aroma. Spices like star anise and cinnamon are present but used in a restrained way, so they support rather than dominate the taste. Many people describe northern pho as gentle and balanced, with less sweetness than southern versions.

The noodles in Hanoi-style pho are often slightly wider, giving a soft but satisfying bite that holds the broth well. Garnishes are minimal: typically just chopped scallions, thinly sliced white onion, cilantro, and perhaps a piece of sawtooth herb. Diners may receive lime and sliced chili, but rarely a large plate of bean sprouts and herbs. Common cuts include rare beef slices (tai), brisket (chin), and flank, usually seasoned only with a small dash of fish sauce and maybe a squeeze of lime at the table. Compared with southern pho, northern bowls use fewer sauces and add-ons, keeping attention on the quality of broth and meat.

Key features of southern (Saigon) pho

The broth in Saigon-style Vietnam pho tends to be a bit sweeter and more aromatic, with stronger notes of star anise, cinnamon, and other spices. Rock sugar or similar sweetener is often added in small amounts to round out the flavor, and the overall taste can feel fuller and more perfumed than northern versions.

Noodles in southern pho are usually thinner, creating a lighter, smoother texture in the bowl. A hallmark of Saigon-style pho is the generous herb and vegetable plate served on the side, which typically includes Thai basil, bean sprouts, lime wedges, fresh chili, and sometimes sawtooth herb and culantro. The range of meat options is also broader, with combinations such as tai nam (rare steak and flank), tai sach (rare steak and tripe), tendon, and beef meatballs (bo vien). Diners in the south frequently customize their bowls with hoisin sauce and chili sauce, which they may add directly into the broth or use as dips for meat. At the same time, it is important to remember that even within the south, styles vary, and not every shop follows exactly the same pattern.

Side-by-side comparison of northern and southern pho

Comparing northern and southern pho side by side helps highlight how regional preference shapes the same base dish in different ways. Both styles share the essential structure of broth, rice noodles, meat, and herbs, but their expressions of sweetness, aroma, and garnishing differ. Neither version is more “authentic” than the other; they simply reflect the tastes and habits of their regions within Vietnam.

The table below summarizes some key differences:

| Element | Northern (Hanoi) Pho | Southern (Saigon) Pho |

|---|---|---|

| Broth flavor | Clear, delicate, strong beef aroma, less sweet, restrained spices | Slightly sweeter, more aromatic, stronger spice presence |

| Noodle width | Often slightly wider, soft but substantial | Usually thinner, lighter texture |

| Herbs and garnishes | Minimal: scallions, cilantro, sliced onion, small amount of lime and chili | Large herb plate: Thai basil, bean sprouts, lime, chili, sometimes sawtooth herb |

| Condiment use | Limited; fish sauce used gently, sauces not always added | Frequent use of hoisin and chili sauces to adjust flavor |

| Overall impression | Subtle, clean, broth-focused | Bold, fragrant, customizable at the table |

For visitors, trying both styles is a good way to understand Vietnam’s regional diversity. Whether you enjoy the restrained elegance of Hanoi pho or the lively, herb-rich character of Saigon pho, both are equally valid expressions of Vietnam pho soup and are celebrated across the country.

Ingredients and Preparation Techniques for Vietnam Pho

How to make authentic pho broth

The broth is the heart of any Vietnam pho recipe, and making it well requires patience and attention to detail. While every family and restaurant has its own method, certain ingredients and steps are common to most traditional approaches. With basic kitchen equipment and a few hours of time, you can produce a broth that captures much of the flavor of a restaurant bowl.

Essential ingredients for a classic beef pho broth include beef bones (often a mix of marrow bones and knuckles), some meaty bones or shank, onion, ginger, and whole spices such as star anise, cinnamon sticks, cloves, coriander seeds, and black cardamom. Seasoning usually comes from salt, fish sauce, and a small amount of rock sugar or regular sugar to round the flavor. The goal is a broth that tastes layered but still light, without greasiness or heaviness.

A simple step-by-step process for making authentic-style pho broth is:

- Blanch the bones: Cover beef bones with cold water, bring to a boil for a few minutes, then drain and rinse. This removes impurities and helps keep the final broth clear.

- Char onion and ginger: Grill, broil, or dry-roast halved onions and sliced ginger until they are lightly blackened. This adds smokiness and depth to the broth.

- Toast the spices: In a dry pan, lightly toast star anise, cinnamon, cloves, and other whole spices until fragrant. This wakes up their flavors.

- Simmer gently: Add cleaned bones, charred onion and ginger, and toasted spices to a large pot. Cover with water, bring just to a boil, then immediately lower to a bare simmer. Skim foam as needed.

- Cook for several hours: Let the broth simmer gently for about 3 to 6 hours. Longer cooking extracts more gelatin and flavor but should still keep the surface only gently moving, not rolling.

- Strain and season: Strain out bones and spices, then season with salt, fish sauce, and a small amount of sugar. Adjust slowly, tasting as you go, until the broth tastes balanced and clean.

By following this process and keeping the heat moderate, you can achieve a clear yet deeply flavored Vietnam pho soup base that works for both northern and southern styles, depending on how much sweetness and spice aroma you prefer.

Rice noodles (banh pho) and how to cook them

Rice noodles, or banh pho, give pho its distinctive texture and make it naturally gluten-free when traditional ingredients are used. They come in two main forms: fresh and dried. Fresh banh pho is soft and slightly elastic, usually sold in Vietnamese markets and used directly after a quick warm-up. Dried banh pho is more widely available in supermarkets and must be soaked and boiled before use.

Noodle width also varies and often reflects regional preferences. Northern-style pho tends to use slightly wider noodles, which feel more substantial and hold broth well, while southern-style pho often uses thinner noodles that slide more softly between the chopsticks. When cooking dried noodles at home, first soak them in warm water for about 20 to 30 minutes until they become flexible but not fully soft. Then boil them in plenty of water for roughly 3 to 6 minutes, depending on thickness, tasting frequently.

Signs that banh pho is done include a fully opaque white color, a tender bite without a hard core, and a texture that is soft but not mushy. After boiling, drain the noodles and rinse briefly with cool water to stop cooking and remove extra starch. If you are not serving immediately, you can toss them lightly with a bit of neutral oil to prevent sticking. When ready to assemble your Vietnam pho soup, place a portion of noodles in each bowl first, then add hot broth and toppings; the residual heat of the broth will warm the noodles through.

Common proteins and popular pho variants

The choice of protein is one of the main ways to customize a bowl of Vietnam pho, and menus usually offer several options based on beef, chicken, or plant-based ingredients. For beef pho, you will often see Vietnamese terms that describe the cut and level of doneness. Understanding these words helps you order exactly what you want in a Vietnam pho restaurant.

Common beef options include tai (thinly sliced rare steak that cooks in the hot broth), chin (well-done brisket with a tender texture), nam (flank, slightly chewy but flavorful), tendon, tripe (sach), and beef meatballs (bo vien). Many bowls combine two or more cuts, such as tai nam (rare steak and flank) or special mixed bowls that include several textures. Chicken pho, called pho ga, uses a lighter broth made from chicken bones and often includes sliced chicken meat, herbs, and sometimes shredded chicken skin or organs, depending on the shop.

Vegetarian and vegan versions of pho are also increasingly popular. In these bowls, a rich vegetable or mushroom broth replaces the bone broth, and proteins come from tofu, tempeh, or various mushrooms. Seasonal vegetables like bok choy, carrots, or broccoli may appear as toppings, keeping the same core structure of noodles, broth, and herbs. For plant-based versions, fish sauce is usually replaced with soy sauce, tamari, or specialized vegan “fish” sauces so that the flavor profile remains close to traditional pho Vietnam food while staying fully meat-free.

Vietnam Pho Recipe (Home Cooking Guide)

Basic beef pho recipe (step-by-step)

Cooking Vietnam pho soup at home may seem challenging, but with a simple plan you can create a satisfying bowl that captures the spirit of a traditional shop. This basic beef pho recipe is designed for home kitchens, balancing flavor with realistic cooking time. Exact amounts can be adjusted to the number of people you are serving and to your personal taste.

For a family-sized batch serving about 4 people, you will need roughly 1.5 to 2 kilograms of mixed beef bones (marrow and knuckle), some meaty bones or shank, 1 to 2 large onions, a piece of ginger about the size of your thumb, a few star anise pods, 1 cinnamon stick, several cloves, and coriander seeds. You will also need flat dried rice noodles, 300 to 500 grams of thinly sliced beef (such as sirloin or eye of round for tai), fish sauce, salt, sugar or rock sugar, and herbs like scallions, cilantro, and Thai basil, plus lime, bean sprouts, and chili for serving.

A practical step-by-step method is:

- Blanch the bones in boiling water for a few minutes, then drain and rinse them under running water to remove impurities.

- Char the halved onions and sliced ginger over an open flame, under a broiler, or in a dry pan until lightly blackened.

- Place cleaned bones, meaty pieces, charred onion, and ginger in a large pot. Add enough water to cover and bring to a boil, then reduce to a gentle simmer.

- Skim foam and fat from the surface during the first 30 to 40 minutes to keep the broth clear.

- Add toasted spices (star anise, cinnamon, cloves, coriander seeds) tied in a small cloth or placed in a tea strainer, and continue to simmer for about 3 to 4 hours.

- Strain the broth, discard bones and spices, and season with fish sauce, salt, and a small amount of sugar. Taste and adjust gradually until balanced.

- Prepare dried banh pho by soaking and boiling as described earlier, then drain and rinse.

- To serve, place noodles in bowls, top with thin slices of raw beef, and pour boiling-hot broth over the top so the meat cooks gently. Finish with herbs and sliced onion, and serve immediately with lime, chili, bean sprouts, and sauces on the side.

This home-style Vietnam pho recipe will not be exactly the same as a specialized restaurant that simmers broth overnight, but it can deliver a deeply satisfying meal and introduce you to the techniques behind pho Vietnam food.

Simple vegetarian Vietnam pho recipe

For those who do not eat meat or who simply want a lighter meal, a vegetarian Vietnam pho soup can be rich and aromatic when prepared with care. The key is to build layers of flavor using vegetables, mushrooms, and spices so that the broth feels complete even without bones. The same structure of noodles, herbs, and condiments still applies, which makes it easy to adapt familiar beef pho methods.

To make a basic vegetarian Vietnam pho recipe, start with onions, carrots, daikon radish, and celery as your base. Add dried or fresh mushrooms such as shiitake or oyster mushrooms to deepen the umami flavor. Char the onion and ginger as you would for beef broth, and toast the same pho spices (star anise, cinnamon, cloves, coriander seeds). Instead of fish sauce, season with soy sauce, tamari, or a plant-based “fish” sauce to keep the characteristic salty-sweet balance. Simmer the vegetables and spices in water for 1.5 to 2 hours, then strain and adjust seasoning with salt and a bit of sugar.

For protein and texture in the bowl, use firm tofu cubes, pan-fried tofu slices, tempeh, or extra mushrooms. Blanch or lightly stir-fry vegetables like bok choy, broccoli, or green beans and add them as toppings. Assemble the bowl in the same way as meat-based pho: cooked rice noodles at the bottom, hot vegetarian broth poured on top, then tofu, vegetables, herbs, and sliced onion. Serve with lime, chili, and bean sprouts. With these substitutions, vegetarian and vegan diners can enjoy a bowl that closely mirrors the structure and comfort of classic Vietnam pho soup.

Cultural Significance and Global Spread of Pho

Pho as a symbol of Vietnamese identity

Within Vietnam, pho is much more than a popular breakfast; it is often seen as a symbol of national identity and resilience. Many Vietnamese people associate the smell of pho broth in the morning with home, family, and childhood. Because it was born as an affordable street food and is still enjoyed by people of all income levels, pho represents everyday life rather than luxury, and it connects different social groups around a shared taste.

Vietnam pho appears frequently in Vietnamese stories, films, and music as a sign of warmth and belonging. Characters meet at pho stalls to talk, reconcile, or celebrate. Parents take children for a special bowl after good exam results, and friends gather at their favorite shop after late-night work or travel. For families that have moved abroad, cooking pho at home or visiting a local Vietnam pho restaurant can be a way to maintain connection with their roots and pass cultural memories to younger generations.

From street food to global comfort food

Originally, pho was sold mainly by street vendors and small stalls with simple settings: low stools, metal or wooden tables, and steam rising from large pots at the front. Over the 20th century, as cities grew and incomes rose, pho spread into more formal restaurants and chains, but the street-side bowl remains an iconic experience for many visitors to Vietnam. This movement from street corners to modern dining rooms shows how pho has adapted while keeping its core character.

After the 1970s, large waves of Vietnamese migration carried pho to many parts of the world. Refugee and immigrant communities opened small Vietnam pho restaurants in their new cities, often starting with very limited resources. Over time, these restaurants became important community centers where Vietnamese people could speak their language, celebrate festivals, and support one another. At the same time, local neighbors discovered pho as a new type of comfort food. Today, it is common to find a Vietnam pho restaurant near you in many major cities, serving office workers at lunch, families at dinner, and students late at night.

Preservation, fusion, and innovation in pho

As pho has spread internationally, it has entered a constant conversation between preservation and innovation. Many traditional shops in Vietnam and abroad focus on maintaining recipes passed down through families, emphasizing slow-simmered broth, specific beef cuts, and careful seasoning. For these cooks, the idea of authenticity is linked to technique, patience, and respect for the ingredients.

At the same time, modern chefs and home cooks experiment with fusion versions of Vietnam pho food. Some create “dry pho,” where noodles and toppings are served with a separate dipping broth. Others design pho-inspired dishes such as pho-flavored burgers, tacos, or even pho-flavored instant noodles. There are also luxury interpretations with premium beef cuts or unusual toppings. While opinions differ on how far innovation should go, a respectful approach tries to keep the essence of Vietnam pho—its clear broth, rice noodles, and herb-based freshness—while allowing room for creativity and local adaptation.

Health, Nutrition, and Dietary Adaptations

Nutritional profile of Vietnam pho soup

Many people are curious whether Vietnam pho soup fits into their regular eating habits from a nutritional point of view. A typical bowl of beef pho provides a mix of carbohydrates from the noodles, protein from the meat, and a moderate amount of fat from both the broth and any visible fat on the beef. The hot broth also contributes to hydration, and the fresh herbs and vegetables add small amounts of vitamins and minerals.

Exact nutrition values vary widely depending on portion size, meat choices, and how the broth is prepared. A medium restaurant bowl might roughly contain a few hundred calories, with a notable portion of that coming from noodles. Using lean cuts such as eye of round or trimmed brisket keeps saturated fat lower, while fatty cuts or large amounts of bone marrow can increase richness and energy content. Herbs like basil and cilantro, along with bean sprouts and lime, add freshness and fiber without many extra calories, making them an easy way to enhance both flavor and perceived lightness.

Is pho a healthy meal choice?

Vietnam pho can be part of a balanced diet when prepared and eaten with some attention to ingredients and portions. Because it combines broth, protein, and carbohydrates in one bowl, it can feel satisfying without the need for many side dishes. Using lean proteins, moderate amounts of noodles, and plenty of herbs and vegetables can help keep the meal relatively light while still comforting.

There are, however, a few points to consider. Some broths are high in sodium due to generous use of salt and fish sauce, and a small amount of sugar is often added for balance. Large portions of noodles can quickly increase total calories, especially if you drink all the broth. To make your bowl lighter, you can ask for fewer noodles, choose lean cuts of meat, and load up on bean sprouts and herbs. Avoiding too much hoisin and chili sauce, which may include sugar and extra salt, is another simple way to keep your Vietnam pho soup closer to your personal nutrition goals. These are general tips rather than medical guidance, and individual needs may differ.

Adapting Vietnam pho for different diets

One strength of pho Vietnam food is its flexibility for different dietary patterns. Traditional pho uses rice noodles, which are naturally gluten-free, so the dish can be suitable for people avoiding gluten, provided that the sauces and seasonings used are also gluten-free. Many restaurants can confirm whether their fish sauce, soy sauce, and other condiments contain wheat-based additives.

For lower-carbohydrate or lower-calorie approaches, some diners request a smaller portion of noodles and more vegetables or even replace part of the noodles with zucchini noodles or other vegetable strips. Others focus on clear broth and lean meats, leaving most of the broth and some noodles in the bowl when finished. Vegetarian and vegan adaptations, described earlier, replace meat and bone broth with plant-based options but keep the same overall structure. Anyone with serious allergies or medical conditions should always talk directly with restaurant staff and check ingredient lists, because recipes and brands of sauces can vary widely between Vietnam pho restaurants and home cooks.

How to Order and Eat Pho with Confidence

Understanding a typical Vietnam pho menu

Reading a Vietnam pho menu for the first time can be confusing because of the Vietnamese terms, but most menus follow a clear system once you know the basics. Dishes are usually grouped by protein type and sometimes by special combinations. Knowing a few key words helps you choose faster and feel more comfortable ordering in any pho Vietnam food restaurant.

Common terms you may see include:

- Pho tai: Pho with rare beef slices that cook in the hot broth.

- Pho chin: Pho with well-done brisket, softer and more cooked through.

- Pho tai nam: A mix of rare steak (tai) and flank (nam).

- Pho bo dac biet: A “special” beef pho with several cuts such as rare beef, brisket, tendon, and tripe.

- Pho ga: Chicken pho, using chicken broth and sliced chicken meat.

Menus may also list sizes (small, medium, large), extra toppings (additional meat, egg, or bones), and side dishes like fried dough sticks or spring rolls. When using a phrase like “Vietnam pho menu” in a search engine, you will often find images or translations of these terms, which can be helpful to review before visiting a restaurant. If you are unsure, pointing to an item or asking staff for a recommendation is perfectly acceptable.

Etiquette and eating customs for pho

Eating pho has a few simple customs that can make the experience smoother and more enjoyable, especially when you are a guest in Vietnam or in a traditional Vietnam pho restaurant elsewhere. These are not strict rules but common practices that show respect for the cook and other diners. Following them can also help you taste the dish as it was intended.

When your bowl arrives, it is customary to taste the broth first before adding any condiments. This allows you to appreciate the chef’s balance of salt, sweetness, and spice. After that first sip, you can adjust the flavor with lime, herbs, and sauces according to your own preference. Chopsticks are used to pick up noodles and pieces of meat, while a spoon is used for the broth. Placing the spoon under the noodles as you lift them can help you bring both broth and noodles to your mouth together. Gentle slurping is normal and can even signal that you are enjoying the hot soup; very loud noises, however, may feel disruptive in quiet settings.

Customizing your pho bowl to your taste

One of the pleasures of Vietnam pho soup is how easily you can customize it at the table. After tasting the original broth, many people squeeze in a bit of lime to add brightness, then decide whether they want more heat or sweetness. Fresh chili slices or chili sauce increase spiciness, while hoisin sauce brings a gentle sweetness and thicker body. Fish sauce can deepen the savory taste if the broth feels too mild.

Some example combinations include a “mild” bowl with only lime and extra herbs for freshness, a “medium” bowl with lime and a small amount of chili sauce, and a “strong” bowl that includes lime, fresh chili, and a bit of fish sauce for intense flavor. A practical tip is to add condiments a little at a time, stir, and taste after each addition. In many pho Vietnam food traditions, diners are encouraged to try a few spoonfuls in the house style before making changes, as a sign of respect for the cook’s work and to better understand the base flavor of that particular restaurant.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Vietnamese pho and what are its main ingredients?

Vietnamese pho is a noodle soup made with a clear, aromatic broth, flat rice noodles, and meat, usually beef or chicken. The broth is simmered from bones with spices such as star anise, cinnamon, cloves, ginger, and onion. Bowls are topped with fresh herbs, onion, and often served with lime, bean sprouts, and chili on the side.

Is pho originally from Vietnam or another country?

Pho is originally from Vietnam, where it developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in the northern regions, especially Nam Dinh and Hanoi. It was influenced by French beef consumption and Chinese noodle and spice traditions but became a distinct Vietnamese dish. Today it is widely regarded as a national food symbol of Vietnam.

What is the difference between northern and southern Vietnamese pho?

Northern Vietnamese pho has a clear, delicate broth, wider noodles, and few garnishes, focusing mainly on pure beef flavor. Southern pho has a slightly sweeter, more strongly spiced broth, thinner noodles, and a large plate of herbs and bean sprouts. Southern bowls usually offer more meat options and heavier use of sauces at the table.

Is Vietnamese pho considered a healthy meal?

Vietnamese pho can be a healthy meal because it provides protein, carbohydrates, fluids, and herbs in one bowl. When the broth is not too salty or sugary and lean cuts of meat are used, it stays moderate in calories and saturated fat. Portion control of noodles and condiments helps keep pho suitable for regular consumption.

How do you eat pho correctly at a Vietnamese restaurant?

To eat pho correctly, first taste the broth before adding any sauces to appreciate its original flavor. Then add herbs, lime, bean sprouts, and chili according to your preference and mix gently. Use chopsticks for the noodles and meat, and a spoon for the broth; slurping is acceptable and shows enjoyment.

Can Vietnamese pho be made vegetarian or vegan?

Vietnamese pho can be made vegetarian or vegan by replacing the bone broth with a rich vegetable or mushroom broth. Seasoning is adjusted with soy sauce or tamari instead of fish sauce, and toppings can include tofu, mushrooms, and vegetables. When done carefully, vegetarian pho can closely match the flavor structure of traditional versions.

How long should pho broth be cooked for good flavor?

Pho broth should usually be simmered gently for at least 3 to 4 hours to develop depth of flavor. Some cooks extend this to 6 hours or more for a richer taste and more gelatin extraction from the bones. The heat should stay at a low simmer to keep the broth clear and clean-tasting.

Conclusion: Enjoying Vietnam Pho Wherever You Are

Key takeaways about Vietnam pho

Vietnam pho is a rice noodle soup that combines clear broth, flat rice noodles, meat or plant-based proteins, and fresh herbs into a balanced, aromatic meal. It emerged in northern Vietnam under the combined influences of local cooking, French beef culture, and Chinese noodle traditions, then spread throughout the country and around the world. Regional styles such as northern (Hanoi) and southern (Saigon) pho differ in broth sweetness, noodle width, and garnish style, but both are authentic reflections of local taste.

Beyond its flavor, pho plays an important cultural role as a symbol of Vietnamese identity, family connection, and everyday resilience. Whether eaten in a small street stall or a modern restaurant, a bowl of Vietnam pho soup expresses the same core idea: simple ingredients transformed through time and care. Knowing its history, structure, and variations allows you to understand and appreciate each bowl more deeply, wherever you encounter it.

Next steps for cooking and tasting pho

With a basic understanding of pho’s components and techniques, you can approach both home cooking and restaurant visits with more confidence. The beef and vegetarian Vietnam pho recipes described here provide starting points for your own kitchen experiments using ingredients available in your local markets. By adjusting herbs, spices, and toppings, you can find a version that fits your tastes and dietary needs while keeping the recognizable structure of broth, rice noodles, and fresh herbs.

As you taste different bowls in various cities and countries, you may notice how each cook and region expresses Vietnam pho in a unique way. Comparing these experiences, and perhaps sharing them with friends or family, is one of the most rewarding parts of exploring pho Vietnam food. Over time, your personal understanding of what makes a memorable bowl of pho will grow, connecting you more closely to both the dish and the culture that created it.

Your Nearby Location

Your Favorite

Post content

All posting is Free of charge and registration is Not required.

![Preview image for the video "13 Hr Pho Broth [Full Recipe is in the Description]". Preview image for the video "13 Hr Pho Broth [Full Recipe is in the Description]".](/sites/default/files/styles/media_720x405/public/oembed_thumbnails/2025-11/Uq-nZQlqdGjQB50zGJsuGJrFowj8ijZZbAYTsi4kn9I.jpg.webp?itok=zUijoQLe)