US Vietnam War: Causes, Timeline, Death Toll, and US Involvement

The Vietnam US War was one of the most important and controversial conflicts of the 20th century. It involved North Vietnam and its allies fighting against South Vietnam, heavily supported by the United States. For many people today, especially travelers, students, and professionals moving between the US and Southeast Asia, this war still shapes political discussions, culture, and memorials they encounter. Understanding why the US went to war with Vietnam, how long US involvement lasted, and how many US soldiers died helps make sense of modern relations between the two countries. This article explains the key causes, timeline, casualty figures, US presidents, the draft, and the meaning of the US Vietnam War memorial in clear, accessible language.

Introduction to the Vietnam US War and Its Global Significance

The Vietnam US War was more than a regional conflict; it became a central event in the global Cold War and left deep marks on international politics, society, and culture. For people from many countries, the war is a reference point when they think about foreign intervention, human rights, and the limits of military power. Even decades later, debates about why the United States entered the Vietnam War and whether it could have acted differently still shape how leaders and citizens think about new crises.

This introduction sets the stage for a detailed look at how and why the United States became involved, what happened during the war, and how its legacy continues. By clarifying the basic facts and terms, readers without a history background can follow the later sections easily. It also helps international readers understand why many discussions about US foreign policy still mention Vietnam, whether they are reading news about current conflicts or visiting museums and memorial sites.

What the Vietnam US War Was and Who the Main Parties Were

The Vietnam War was a conflict fought mainly in Vietnam from the mid-1950s until 1975. On one side was North Vietnam, led by a communist government under Ho Chi Minh, supported by the Soviet Union and China. On the other side was South Vietnam, officially called the Republic of Vietnam, which was anti-communist and received strong military, economic, and political support from the United States and some allied countries. Because the United States played such a large role, many people outside Vietnam refer to the conflict as the US Vietnam War or the Vietnam US War.

The war began after the earlier First Indochina War, when French colonial rule ended and Vietnam was temporarily divided into North and South at the 17th parallel. What started as a civil and regional struggle gradually drew in outside powers, especially the US, which first sent advisers and then large combat forces. The timeline usually runs from around 1954, after the Geneva Accords, to April 1975, when Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam, fell to North Vietnamese forces. After that, Vietnam was reunified under a single communist government, officially becoming the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

Why Understanding US Involvement in the Vietnam War Still Matters Today

Understanding the US role in the Vietnam War matters today because the conflict still influences how governments think about military interventions. Many discussions about whether the US or other countries should send troops abroad refer back to Vietnam as an example of how complex local politics, public opinion, and long wars can limit what military force can achieve. Concepts such as “mission creep,” “quagmire,” and concerns about unclear goals in foreign wars often come from lessons people draw from the Vietnam experience.

The war also left deep marks on people and societies in both the United States and Vietnam. Millions of veterans, families, and civilians were affected by loss, injury, and displacement. In the US, the Vietnam War helped shape the civil rights movement, youth culture, and trust in government, while in Vietnam it remains a central part of national history and identity. For travelers, students, and remote workers moving between the US and Southeast Asia, having this historical context can help them understand local museums, memorials, and conversations about the war, without getting lost in country-specific political arguments.

Overview of the Vietnam War and US Involvement

To understand the Vietnam US War, it helps to start with a clear overview of what happened and how the United States was involved. The war took place mainly in South Vietnam, North Vietnam, and neighboring areas of Laos and Cambodia. It involved not only regular armies but also guerrilla forces, air campaigns, and large-scale bombing operations.

The United States’ role evolved over time. At first, American involvement focused on financial aid, training, and military advice to help South Vietnam resist communist forces. Later, the US deployed hundreds of thousands of combat troops, conducted widespread air strikes, and led major ground operations. Eventually, it shifted back toward training and supporting South Vietnamese forces before withdrawing nearly all combat troops. The conflict ended in 1975 when North Vietnamese forces captured Saigon, leading to the unification of Vietnam under communist rule, while the US faced a painful reassessment of its foreign policy and military strategy.

Key Facts About the US in the Vietnam War

A few key facts help frame the scale and nature of US Vietnam War involvement. The United States began sending small numbers of military advisers to Vietnam in the 1950s, with the advisory role expanding under President John F. Kennedy in the early 1960s. Full-scale combat operations began after 1965, when large ground units and extensive air power were deployed. The peak number of US troops in Vietnam was around half a million service members in the late 1960s, showing how central the war had become for American policy.

The human cost for the United States was high. About 58,000 US military personnel died in the conflict, and many more were wounded or suffered long-term effects. The war ended for the US with the withdrawal of most combat forces by early 1973, after the Paris Peace Accords. For Vietnam, however, the fighting continued until 1975, when Saigon fell and the country was reunified under the North Vietnamese government. US forces during the war included ground troops such as the Army and Marines, air power from the Air Force and Navy, and naval forces operating in nearby waters, including aircraft carriers and support ships.

Major Phases of US Vietnam War Involvement

US involvement in the Vietnam War can be divided into several distinct phases that show how the American role changed over time. In the first phase, during the 1950s and early 1960s, the US mainly provided advisers, training, and equipment to the French and later to the South Vietnamese government. American policy makers hoped that limited support would be enough to prevent a communist takeover without committing large combat forces.

The second phase began after the Gulf of Tonkin incidents in 1964, when reported clashes between US naval vessels and North Vietnamese forces led to the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in the US Congress. This resolution gave the president broad authority to use military force in Southeast Asia without a formal declaration of war. Starting in 1965, large US combat units deployed to Vietnam, marking a period of major escalation with intense ground battles and heavy bombing campaigns.

The third phase is known as “Vietnamization,” a policy introduced under President Richard Nixon. From about 1969 onward, the US started to reduce its troop levels while increasing efforts to train and equip South Vietnamese forces to take over more of the fighting. During this time, peace negotiations were underway, eventually leading to the Paris Peace Accords in 1973, which called for a cease-fire and the withdrawal of remaining US combat troops. The final phase occurred after US forces had mostly left, when the United States limited its role to financial and material support for South Vietnam, while North Vietnamese forces eventually launched a successful offensive that ended with the fall of Saigon in 1975.

Why Did the United States Get Involved in the Vietnam War?

The United States became involved in the Vietnam War mainly because its leaders wanted to stop the spread of communism in Southeast Asia during the global Cold War. They believed that if South Vietnam fell under communist control, neighboring countries might follow, a fear known as the domino theory. Over time, this goal led the US to move from financial aid and advisory roles into direct military intervention.

US involvement was also influenced by alliances, domestic politics, and the desire to protect American credibility as a global power. Supporting South Vietnam was seen as part of a broader strategy of “containment,” which aimed to limit the expansion of Soviet and Chinese influence. US presidents worried that withdrawing or refusing to help would send a signal of weakness to both allies and rivals. These ideas shaped decisions taken by different administrations, even as public opinion at home grew more divided.

Cold War, Containment, and the Domino Theory

The Cold War was a long period of tension and competition between the United States and its allies on one side, and the Soviet Union, China, and their allies on the other. It was not a single open conflict but a global struggle for influence, fought through economic aid, diplomacy, local wars, and nuclear arms races. In this context, US leaders saw events in Vietnam not only as a local issue but as part of a larger battle between communism and non-communism worldwide.

US foreign policy during this time followed a strategy called “containment.” Containment meant trying to prevent communism from spreading to new countries, even if that meant supporting governments that were imperfect or unstable. The “domino theory” was a specific idea within this strategy. It suggested that if one country in a region fell to communism, others nearby might fall like a line of dominoes. Applied to Southeast Asia, US leaders argued that if South Vietnam became communist, countries such as Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, and perhaps others could follow.

This fear appeared in official speeches, policy documents, and decisions. For example, presidents and senior officials often described Vietnam as a test of US commitment to defend its allies. They believed that backing away might encourage communist movements and discourage friendly governments. While historians today debate how accurate the domino theory was, there is broad agreement that it strongly shaped US thinking and helped explain why the United States chose to go to war with Vietnam rather than accept a communist victory in the South.

Early US Support for South Vietnam Before Full-Scale War

US involvement in Vietnam did not begin with ground combat troops. It started earlier, with financial and military assistance during the First Indochina War, when France was trying to maintain its colonial control over Vietnam against the Viet Minh, a nationalist and communist movement. In the early 1950s, the US paid a large share of the French war costs because it saw France as a key ally against the Soviet Union. When France was defeated in 1954 at Dien Bien Phu and agreed to withdraw, the focus shifted from supporting a colonial power to supporting a new, anti-communist state in the South.

After the Geneva Accords in 1954, Vietnam was temporarily divided. The Republic of Vietnam was formed in the South under President Ngo Dinh Diem. The United States recognized and supported this new government, seeing it as a barrier against communism in the region. Under President Dwight D. Eisenhower, the US provided financial assistance, training, and equipment to build up South Vietnam’s army and administration. American military advisers were sent to help plan operations and improve local forces, but they were not officially there to lead combat.

When John F. Kennedy became president in 1961, he increased the number of US advisers and support personnel, including some elite units and helicopter crews. While these advisers sometimes took part in fighting, the official US role was still described as “advisory” rather than open warfare. At the same time, South Vietnam faced serious internal problems: political instability, corruption, and growing insurgency by communist-led forces known as the Viet Cong. These challenges made it difficult for the South Vietnamese government to gain broad public support, which later contributed to pressure for greater US involvement and, eventually, direct combat operations.

When Did the United States Enter the Vietnam War?

The United States began its involvement in Vietnam in the 1950s with aid and advisers, but it formally entered the Vietnam War with large combat forces in 1965. Before that, the American presence grew step by step rather than all at once. This gradual escalation can make it difficult to give a single start date, so it is helpful to distinguish between early advisory years and the later period of full-scale war.

From the late 1950s through the early 1960s, the US increased the number of military advisers and support staff in South Vietnam. The turning point came after the Gulf of Tonkin incidents in 1964 and the resulting Gulf of Tonkin Resolution passed by Congress. This resolution allowed the president to use military force in Southeast Asia without an official declaration of war. In March 1965, the first major US Marine combat units landed in South Vietnam, followed by rapid growth in troop numbers over the next few years. By the late 1960s, the United States was deeply engaged in active, large-scale combat operations.

From Advisers to Combat Troops in the US Vietnam War

The shift from advisers to combat troops in the Vietnam US War took place over about a decade. At first, American personnel focused mainly on training and support, but gradual steps increased their role until the US was leading major military operations. Understanding this sequence helps clarify why different sources sometimes give different dates for when the US “joined” the Vietnam War.

A simple mini-timeline of escalation is:

- Early 1950s: The United States provides financial aid and limited military support to the French in the First Indochina War.

- Mid-1950s to late 1950s: After the Geneva Accords, the US begins supporting the new South Vietnamese government with advisers and funding.

- Early 1960s: Under President Kennedy, the number of US advisers increases sharply, and some are involved in combat-related operations, though the official mission remains advisory.

- 1964: The Gulf of Tonkin incidents lead to the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, giving the president broad authority to use military force in Southeast Asia.

- 1965: Major US combat units, including Marine infantry and Army divisions, deploy to South Vietnam, and large-scale bombing of North Vietnam begins. This period is widely seen as the start of full US combat involvement.

This progression shows that US involvement was not a single event but a chain of decisions. Advisers and special units were present for years before the first official combat formations arrived. Once large ground forces and intensive air campaigns were committed, the US role changed from supporting South Vietnamese efforts to directly fighting North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces on a daily basis.

How Long Was the United States Involved in the Vietnam War?

The United States was involved in Vietnam for roughly two decades, but the most intense combat period lasted about eight years. Significant numbers of advisers and support personnel were present from the mid-1950s, and full combat operations involving large ground forces occurred mainly between 1965 and 1973. After 1973, US direct combat largely ended, although the conflict within Vietnam continued until 1975.

To understand these overlapping timelines, it is useful to separate advisory involvement, peak combat operations, and the final stages of the war. Advisers began arriving in the 1950s and early 1960s, with their numbers steadily growing. Combat operations intensified as troop levels rose after 1965, peaking in the late 1960s. In January 1973, the Paris Peace Accords were signed, leading to a cease-fire and the withdrawal of US combat troops. However, fighting between North and South Vietnamese forces continued after US forces left. The war itself ended on April 30, 1975, when North Vietnamese troops entered Saigon and the South Vietnamese government collapsed. This means that while US combat ended in 1973, the end of the war inside Vietnam did not come until two years later.

US Presidents During the Vietnam War

Several US presidents played important roles in shaping the course of the Vietnam US War. From the 1950s to the mid-1970s, each administration made decisions that increased, modified, or reduced American involvement. Understanding which president was in office at different times helps explain why US policy changed over the life of the conflict.

The main presidents associated with the Vietnam War are Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, Richard Nixon, and Gerald Ford. Eisenhower and Kennedy expanded advisory missions and support for South Vietnam. Johnson ordered major escalation and introduced large numbers of US combat troops. Nixon reduced troop numbers under a policy called Vietnamization and negotiated the withdrawal of US forces. Ford oversaw the final fall of Saigon and the evacuation of remaining American personnel and some South Vietnamese allies. Although their approaches differed, all of these leaders were influenced by Cold War concerns and domestic political pressures.

Table of US Presidents and Key Vietnam War Actions

The following table summarizes the main US presidents during the Vietnam War period, their years in office, and their key Vietnam-related decisions. This overview shows how leadership changes often brought shifts in strategy, even as some goals, such as supporting South Vietnam, remained consistent.

| President | Years in Office | Key Vietnam War Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Dwight D. Eisenhower | 1953–1961 | Supported France in the First Indochina War; recognized South Vietnam; began large-scale financial and military aid; sent initial US advisers. |

| John F. Kennedy | 1961–1963 | Increased the number of US military advisers and support personnel; expanded training and equipment programs for South Vietnamese forces; approved some covert operations. |

| Lyndon B. Johnson | 1963–1969 | Oversaw the Gulf of Tonkin escalation; obtained the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution; authorized major deployment of US combat troops and large bombing campaigns. |

| Richard Nixon | 1969–1974 | Introduced Vietnamization to shift fighting to South Vietnamese forces; reduced US troop levels; expanded air war at times; negotiated the Paris Peace Accords and US withdrawal. |

| Gerald Ford | 1974–1977 | Managed reduced US support as Congress limited funding; oversaw evacuation of US personnel and some South Vietnamese during the fall of Saigon in 1975. |

Each president’s decisions reflected not only personal views but also domestic politics and international events. For example, the growth of anti-war protests during Johnson’s and Nixon’s presidencies influenced their strategies and public communication. Likewise, changes in Congress and public opinion during Ford’s term limited what the US could do as South Vietnam collapsed.

How Leadership Changes Shaped US Strategy in Vietnam

Leadership changes in Washington had a direct impact on US strategy in the Vietnam US War. While all of the presidents from Eisenhower to Ford saw Vietnam through the lens of the Cold War, they differed in how willing they were to send troops, how they balanced military and diplomatic efforts, and how they responded to growing opposition at home. Elections and shifts in public opinion put pressure on presidents to adjust their approaches over time.

Under Johnson, the fear of appearing weak against communism and the belief that more force could secure victory led to rapid escalation. At home, however, the rising number of casualties, televised images of the war, and the draft sparked protests and criticism. When Nixon took office, he faced a population tired of the conflict. In response, he promoted Vietnamization, aiming to reduce American casualties by having South Vietnamese forces take on more combat, while still trying to preserve a non-communist South. Eventually, negotiations and domestic pressure led to the Paris Peace Accords and the withdrawal of US combat troops. By the time Ford became president, the US focus had shifted mainly to humanitarian concerns, such as evacuating at-risk people, rather than attempting to alter the military outcome. These changes show how political leadership, public opinion, and battlefield realities combined to shape the overall course of US involvement.

US Vietnam War Draft and Military Service

The Vietnam US War depended not only on political leaders and generals but also on millions of ordinary people who served in the military. During this period, the United States used a draft system, also known as conscription, to select young men for compulsory service. This system became one of the most controversial aspects of the war, especially as casualty numbers rose and public support declined.

The Selective Service System managed the process, requiring men to register around age 18. Many were later subject to a draft lottery that determined the order in which they could be called for service. Some received deferments or exemptions, for example due to student status, medical conditions, or family responsibilities. Others volunteered for service rather than waiting to be drafted. The draft and the broader question of who bore the burden of fighting led to protests, legal challenges, and changes in US military policy that still have effects today.

How the Vietnam War Draft Worked for Young Americans

For young Americans during the Vietnam War, the draft was a powerful reality that could shape their education, careers, and even their lives. The basic system was managed by the Selective Service, which maintained records of who was eligible and organized the process of calling people into military service. Understanding the steps in this system helps explain why it caused so much concern and debate.

The draft process during the Vietnam War can be summarized in a few main steps:

- Registration: Young men in the United States were required to register with the Selective Service, usually around their 18th birthday. This created a pool of individuals who could be called up if needed.

- Classification: Local draft boards reviewed each person’s situation and assigned a classification. This classification reflected whether the person was available for service, deferred, exempt, or disqualified, for example due to health reasons.

- Draft Lottery (from 1969): Birth dates were drawn at random, and those with lower numbers were called earlier, while higher numbers were less likely to be drafted.

- Deferments and Exemptions: Some individuals could delay or avoid service through deferments, such as for full-time university study, or exemptions for medical issues, certain occupations, or family responsibilities. These rules led to controversy, because critics argued that they favored those with more resources or education.

- Induction or Alternative Paths: Those selected and found fit for duty were inducted into the armed forces, while others chose to enlist voluntarily in a specific branch to have more control over their role. Some people resisted the draft through legal challenges, conscientious objector status, or, in some cases, by leaving the country.

The draft system became a major focus for anti-war activism. Many people felt it was unfair because the burden of combat seemed to fall more heavily on working-class and minority communities. Protests, public debates, and reforms eventually contributed to the end of the draft after the war, and the United States moved to an all-volunteer military force.

Experiences of US Soldiers and Draftees in the Vietnam War

The experiences of Americans who served in the Vietnam US War were diverse, depending on whether they were draftees or volunteers, their branch of service, their role, and where they were assigned. Some joined voluntarily out of a sense of duty, family tradition, or desire for training and benefits. Others were drafted and felt they had limited choice. Together, they represented a wide range of backgrounds, regions, and social groups in the United States.

After induction, most soldiers went through basic training, followed by more specialized instruction depending on their job, such as infantry, artillery, aviation, communications, or medical support. Many then deployed to South Vietnam, typically for tours of about one year. Their duties could include patrolling rural areas, defending bases, flying helicopters or planes, providing logistics and maintenance, or working in hospitals and support units. Conditions were often difficult: hot and humid climate, unfamiliar terrain, and the constant threat of ambushes, mines, and other dangers.

Beyond physical risks, service in Vietnam involved significant psychological stress. Combat operations, witnessing casualties, and uncertainty about the war’s progress affected many people. After returning home, some veterans found it hard to adjust, facing not only personal challenges such as injuries or trauma, but also a society deeply divided over the war. Unlike some earlier conflicts, many Vietnam veterans did not receive a clear or unified welcome. Over time, recognition of issues such as post-traumatic stress, long-term health problems, and the need for support systems led to changes in how governments and communities respond to returning service members.

US Vietnam War Casualties and Losses

The human cost of the Vietnam US War was extremely high for all sides involved. For the United States, about 58,000 military personnel died as a result of the conflict, and hundreds of thousands were wounded or otherwise affected. These figures represent both combat deaths and non-combat deaths linked to service in the war zone.

Casualties in Vietnam itself were far higher, including large numbers of North Vietnamese and South Vietnamese soldiers, as well as civilians caught in the fighting and bombing. Estimates of Vietnamese deaths vary widely and are harder to confirm, which is why careful language is important when discussing them. While this section focuses on US losses, it is essential to remember that the war’s impact was much greater in Vietnam, where it took place on local soil and affected almost every part of society.

Table of US Vietnam War Casualty Numbers

Casualty numbers help show the scale of US losses in the Vietnam War, although each number also represents an individual life and family. The figures below are approximate but widely accepted and are often used in official commemorations and educational materials.

| Category | Approximate Number |

|---|---|

| US military deaths (all causes related to the war) | About 58,000 |

| US military wounded | Roughly 150,000–300,000 |

| Missing in action (MIA) | Several thousand initially; most later accounted for |

| Prisoners of war (POW) | Hundreds held by North Vietnamese and allied forces |

These numbers are consistent with the figures reflected on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., where more than 58,000 names are engraved. While exact totals for all categories can differ slightly depending on the source and criteria used, the scale of the losses is clear. In addition, many veterans suffered long-term physical injuries, exposure-related health problems, or psychological trauma that do not appear in simple casualty tables but are part of the overall impact of the war.

Human Impact of the Vietnam US War on All Sides

Beyond statistics, the human impact of the Vietnam US War was felt in families, towns, and communities across the United States. Almost every region of the country lost service members, and many schools, workplaces, and universities saw classmates or colleagues drafted, deployed, or killed. Memorials, plaques, and local ceremonies across the US continue to recognize those who served and those who did not return.

In Vietnam, the scale of the losses was far greater, involving not only soldiers from North and South but also millions of civilians. Villages were destroyed, farmland was damaged, and large numbers of people were displaced, injured, or killed. While exact numbers are difficult to confirm, historians generally agree that Vietnamese casualties, including both military and civilian deaths, were several million. The war also left unexploded ordnance and environmental damage that continue to affect communities long after the fighting ended.

Long-term effects include missing persons whose fate remains uncertain, families who never received full information about loved ones, and the ongoing health and psychological needs of veterans and civilians. Issues such as post-traumatic stress, physical disabilities, and social disruption are part of the war’s legacy on both sides of the Pacific. These human dimensions are important to remember when discussing strategic outcomes, because they highlight the costs borne by individuals and societies.

Did the United States Win or Lose the Vietnam War?

Most historians and observers agree that the United States did not win the Vietnam War. Its main goal was to prevent the fall of South Vietnam to communism, but in 1975 North Vietnamese forces captured Saigon and unified the country under a communist government. In this sense, the US failed to achieve its central political objective.

However, evaluating victory and defeat in such a complex conflict is not always simple. US and South Vietnamese forces won many individual battles and inflicted heavy losses on their opponents, but these tactical successes did not translate into lasting strategic or political success. At the same time, domestic opposition to the war, high casualties, and doubts about the effectiveness of continued fighting led US leaders to seek negotiated withdrawal. These factors together help explain why many people say the United States lost the Vietnam War, while still recognizing that the military situation on the ground was often more complicated than a simple win-loss record suggests.

Main Reasons the United States Lost the Vietnam War

Analysts and historians have offered many explanations for why the United States lost the Vietnam US War, and there is still debate about the relative importance of each factor. Nonetheless, some widely discussed reasons appear often in historical writing. One is that US leaders underestimated the determination and resilience of North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces, who were willing to accept extremely high casualties and long years of fighting to achieve unification.

Another important factor was the nature of the conflict itself. Much of the fighting took place as guerrilla warfare in rural areas, where small units used ambushes, hit-and-run tactics, and local knowledge of the terrain. This made it hard for a technologically advanced but foreign army to secure lasting control, even with superior firepower. The South Vietnamese government faced serious problems of corruption, instability, and limited support in some areas, which weakened its legitimacy and ability to mobilize the population. Inside the United States, the growing anti-war movement, media coverage of casualties and destruction, and political divisions put pressure on leaders to limit escalation and eventually reduce involvement. These and other factors combined to make the US position unsustainable over time.

Military Results Versus Political Outcomes in the Vietnam US War

To understand the outcome of the Vietnam War, it is useful to distinguish between tactical, strategic, and political results. A “tactical” outcome refers to what happens in individual battles or operations, such as whether a particular base is defended or a specific enemy unit is destroyed. A “strategic” outcome concerns the overall direction of the war, including control of territory, strength of forces, and long-term prospects for victory. A “political” outcome focuses on changes in governments, policies, and public opinion that result from the conflict.

In Vietnam, US and South Vietnamese forces often achieved tactical successes, winning many battles and inflicting heavy losses. However, these victories did not always lead to lasting strategic gains, partly because the opposing forces could replace their losses and continue fighting. Politically, the war had severe consequences for both Vietnam and the United States. In Vietnam, it ended with the collapse of the South and the unification of the country under a communist regime. In the US, it led to deep public mistrust of government statements, major changes in laws about war powers and the draft, and a lasting caution about large-scale ground interventions. Debates continue about whether different strategies might have changed the outcome, but there is broad agreement on the basic facts: the US left without securing its original goals, and North Vietnam ultimately achieved unification.

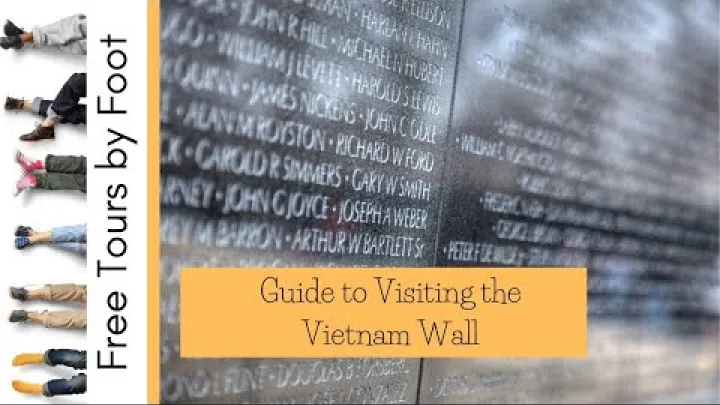

The US Vietnam War Memorial: Purpose and Meaning

The most widely known US Vietnam War memorial is the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. This national monument honors members of the US armed forces who served in the Vietnam War, especially those who died or went missing. It serves as a place of remembrance and reflection for veterans, families, and visitors from many countries.

The memorial was created not to celebrate victory or defeat, but to recognize the human cost of the war and provide a space for healing. Its design is simple but powerful, centered on a long, polished black granite wall engraved with the names of more than 58,000 Americans who were killed or remain missing in the conflict. Over the years, it has become one of the most visited and emotionally significant sites in the United States, illustrating how societies remember difficult and controversial wars.

Design, Location, and Symbolism of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial is located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., near other major landmarks such as the Lincoln Memorial. Its main feature, often called “the Wall,” is set partly below ground level and arranged in a V shape. The two long panels of black granite meet at a central angle and gradually rise in height as they extend outward. Visitors walk along a pathway next to the Wall, which allows them to approach the engraved names closely.

More than 58,000 names are carved into the granite, representing US service members who died or are listed as missing in action in the Vietnam War. The names are arranged in chronological order by the date of death, starting from the middle of the V and moving outward, then returning to the center. This ordering shows the passing of time and the continuity of loss throughout the conflict. The polished surface of the stone acts like a mirror, reflecting the faces of visitors as they look at the names. This design choice encourages personal reflection, as people can literally see themselves against the backdrop of the engraved names. The simplicity of the memorial, without large statues or dramatic scenes, focuses attention on individuals rather than on weapons or battles, making the site a quiet place for remembrance rather than a statement about the politics of the war.

Visiting the Vietnam Veterans Memorial: Practical Information and Etiquette

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial is open to the public and is generally accessible at all hours, although visitor services may follow specific schedules. It is located on the National Mall in central Washington, D.C., within walking distance of other monuments and museums. Many visitors come as part of school trips, family visits, or personal pilgrimages, while others encounter it while exploring the city’s landmarks.

Common practices at the memorial include tracing or rubbing names onto paper using a pencil or crayon, leaving flowers, photos, letters, or small personal items at the base of the Wall, and spending time in quiet reflection. Visitors are encouraged to behave respectfully, recognizing that the site is meaningful to many people who lost friends or family members. This usually means speaking softly, not climbing on the Wall, and being mindful when taking photographs. People from different cultures may have their own ways of showing respect, such as bowing, praying, or leaving symbolic objects, and the memorial is intended as a welcoming space for all these forms of remembrance.

Frequently Asked Questions

When did the United States officially enter the Vietnam War with combat troops?

The United States officially entered the Vietnam War with large-scale ground combat troops in 1965. Before that, from the 1950s and early 1960s, the US had military advisers and support personnel in South Vietnam. After the Gulf of Tonkin incident in 1964, Congress passed a resolution that allowed major escalation. By mid-1965, tens of thousands of US combat soldiers were deployed, marking full-scale US military involvement.

How many US soldiers died in the Vietnam War in total?

About 58,000 US military personnel died as a result of the Vietnam War. The widely cited official figure is just over 58,000 names listed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. In addition, hundreds of thousands of Americans were wounded or suffered long-term physical and psychological effects. These numbers reflect the heavy human cost of the conflict for the United States.

Why did the United States get involved in the Vietnam War?

The United States got involved in the Vietnam War mainly to contain the spread of communism during the Cold War. US leaders believed that if South Vietnam fell to communism, other countries in Southeast Asia might follow, a view often called the domino theory. The US also wanted to support the government of South Vietnam against communist forces backed by North Vietnam. Over time, this support grew from financial aid and advisers into full-scale military intervention.

How long did US military involvement in the Vietnam War last?

US military involvement in Vietnam lasted roughly two decades, from the mid-1950s to 1975, with peak combat operations between 1965 and 1973. The first US military advisers arrived in significant numbers in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Large ground combat units were deployed from 1965, and most US combat troops were withdrawn by early 1973 under the policy of “Vietnamization.” The war in Vietnam ended in April 1975 with the fall of Saigon, although US ground combat had already ceased.

Which US presidents were in office during the Vietnam War years?

Several US presidents were in office during the Vietnam War period, each shaping US policy in different ways. Dwight D. Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy increased American aid and advisory roles in the 1950s and early 1960s. Lyndon B. Johnson ordered major escalation and deployed large combat forces from 1965. Richard Nixon later pursued “Vietnamization” and negotiated US withdrawal, with the last US combat troops leaving in 1973. Gerald Ford was president when Saigon fell in 1975 and oversaw final evacuations.

Did the United States win or lose the Vietnam War, and why?

The United States is generally considered to have lost the Vietnam War because it failed to achieve its main goal of preserving a non-communist South Vietnam. Despite significant military power and many tactical victories, the US and its South Vietnamese allies could not secure lasting control over the country. Factors behind the defeat included strong North Vietnamese and Viet Cong resilience, effective guerrilla tactics, limited legitimacy and strength of the South Vietnamese government, and declining public and political support for the war inside the United States.

What is the Vietnam Veterans Memorial and what does it commemorate?

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial is a national monument in Washington, D.C., that honors US service members who fought and died in the Vietnam War. Its most famous element is a long, V-shaped black granite wall engraved with the names of more than 58,000 Americans who were killed or went missing in action. The memorial is designed as a quiet place for reflection, remembrance, and healing for veterans, families, and visitors. It symbolizes the human cost of the war rather than making a political statement about the conflict itself.

How did the Vietnam War draft work for young Americans?

The Vietnam War draft selected young American men for compulsory military service using a system managed by the Selective Service. Men usually registered around age 18, and beginning in 1969 a lottery based on birth dates was used to decide the order in which they could be called. Some people received deferments or exemptions, for example for student status, medical reasons, or certain family situations. The draft was widely debated and protested, and it ended after the war, with the US moving to an all-volunteer military force.

Conclusion: Lessons and Lasting Legacy of the Vietnam US War

Key Takeaways About the US Vietnam War for Modern Readers

The Vietnam US War was a long and complex conflict that grew out of Cold War tensions, efforts to contain communism, and struggles within Vietnam itself. The United States moved from advising and funding South Vietnam to fighting a major war with hundreds of thousands of troops. Between the mid-1950s and the fall of Saigon in 1975, the conflict took millions of lives, including about 58,000 US service members, and caused deep political and social changes in both countries.

The war’s outcome, in which North Vietnam ultimately unified the country under a communist government, showed the limits of military power when political and social conditions are not favorable. It also led to long-term changes in US foreign policy, military planning, and public attitudes toward intervention abroad. For modern readers, understanding the causes, timeline, casualty figures, and legacy of the Vietnam War helps make sense of ongoing debates about when and how countries should use force, and reminds us of the human costs involved on all sides.

Further Study, Travel, and Reflection on the Vietnam US War

For those who wish to learn more about the Vietnam US War, there are many paths to deeper understanding.

In Washington, D.C., and other American cities, memorials like the Vietnam Veterans Memorial provide spaces to reflect on the names and stories of those who served. For students, professionals, and remote workers who move across borders, this knowledge offers useful context for conversations and media they may encounter. The Vietnam War remains a significant example of how international politics, local conditions, and human choices come together in ways that shape history for generations.

Your Nearby Location

Your Favorite

Post content

All posting is Free of charge and registration is Not required.