Indonesia Empire: history of Srivijaya, Majapahit, Islamic sultanates, and maps

People often search for “Indonesia empire” to understand how power worked across one of the world’s largest archipelagos. Rather than a single empire, Indonesia’s history features a sequence of regional states with changing influence over sea lanes and ports. This guide explains how those empires formed, what they ruled, and why maritime trade mattered. It also clarifies myths about an “Indonesia empire flag,” offers a timeline, and covers events like the Chola raids of 1025.

Quick answer: Was there an “Indonesian Empire”?

There was no single empire that ruled all of Indonesia across all eras. Instead, different polities rose and fell, often commanding trade routes rather than fixed inland borders. The question “Is Indonesia an empire?” is also time-sensitive: the modern Republic of Indonesia has been a sovereign nation-state since 1945, not an empire. To understand the phrase “Indonesia empire,” it helps to see how premodern states in the archipelago projected influence in layered, flexible ways over centuries, especially by sea.

What historians mean by "empires in Indonesia"

When historians discuss empires in Indonesia, they refer to multiple regional powers operating at different times, not one continuous state. Influence often followed a “mandala” model, a term that describes a political sphere with a strong core and softer edges of influence that fade with distance. In this system, authority was layered: some areas were directly ruled, others paid tribute, while distant ports might align through diplomacy. A “thalassocracy,” or sea-based state, is a polity whose strength rests on maritime trade, fleets, and control of coastal hubs rather than on farming hinterlands.

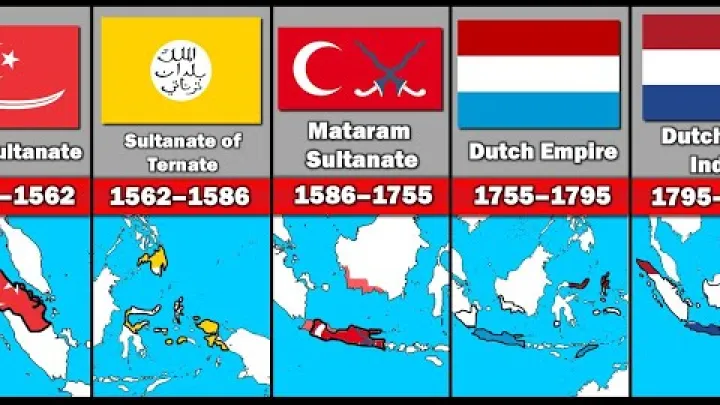

Key phases include Srivijaya (roughly 7th–13th centuries), Majapahit (1293–c.1527), and later Islamic sultanates that flowered from the 15th to the 18th centuries. Each phase had its own political vocabulary and styles of rule. Tribute could mean gifts and recognition, alliances could be cemented by marriage, and direct rule could exist in core regions. Understanding the diversity of arrangements, and the wide date ranges, helps explain why maps and modern categories cannot capture all the nuance of these layered empires.

Why trade routes and sea power shaped Indonesian empires

Indonesia sits astride two oceanic worlds: the Indian and the Pacific. The Strait of Malacca and the Sunda Strait are chokepoints where ships must pass, making them prime sites for customs, protection, and influence. Seasonal monsoon winds, combined with evolving shipbuilding and navigation, made long-distance voyages predictable. As a result, ports became wealth generators, and rulers who secured harbors, pilots, and convoys could channel international commerce, including the spice trade, through their domains.

Representative hubs show this pattern in action. Palembang was central to Srivijaya’s network in Sumatra; Malacca later rose as a cosmopolitan port on the Malay Peninsula; Banten emerged near the Sunda Strait as a pepper-rich node. Sea-focused polities projected authority across dispersed islands with fleets, beacons, and treaties, while inland agrarian states concentrated power where river valleys and rice fields anchored settlements. In the archipelago, maritime influence often outpaced inland expansion, so hegemony meant safeguarding sea-lanes and port alliances more than drawing fixed frontier lines.

Key empires and sultanates, at a glance

The major powers in Indonesian history paired maritime opportunity with local conditions. Srivijaya leveraged Sumatra’s position to dominate critical straits. Majapahit blended land-based resources in East Java with naval reach across many islands. Later, Islamic sultanates like Demak, Aceh, and Banten tied religious scholarship to commercial diplomacy and pepper routes. Colonial-era structures then remade trade and governance under foreign corporate and imperial systems.

Srivijaya: maritime power and Buddhist center (7th–13th c.)

Srivijaya was based near Palembang in southeastern Sumatra and built strength by commanding the Strait of Malacca and associated routes. It prospered by taxing trade, offering safe passage, and acting as a staging post between South and East Asia. As a Mahayana Buddhist center, it fostered learning and hosted pilgrims, integrating religious prestige with diplomatic ties that linked the Bay of Bengal, the South China Sea, and beyond.

Key inscriptions anchor its chronology and reach. The Kedukan Bukit inscription (dated to 682) and the Talang Tuwo inscription (684) near Palembang record royal foundations and ambitions. The Ligor inscription on the Malay Peninsula (often associated with the late 8th century) and evidence from the Nalanda inscription in India (linking King Balaputradeva) attest to Srivijaya’s international profile. Srivijaya’s fortunes shifted after 11th-century disruptions, including raids by the Chola Empire of South India and pressure from regional rivals, which eroded its dominance of straits and ports.

Majapahit: land–sea strength and archipelagic reach (1293–c.1527)

Majapahit formed in East Java after a Mongol expedition was diverted and defeated, with its capital centered on Trowulan. The empire combined agricultural bases in Java with naval patrols and coastal alliances to project force across the archipelago. At its peak under Hayam Wuruk and the famous prime minister Gajah Mada, Majapahit’s influence reached many islands and coastal polities, supported by tribute, treaties, and strategic marriages rather than uniform annexation.

It is crucial to distinguish core territories from looser spheres. Core lands included East Java, parts of Madura, and nearby regions with direct bureaucratic control. Spheres of influence extended via ports and vassals into Bali, parts of Sumatra’s coasts, Borneo’s southern and eastern ports, Sulawesi nodes, and the Nusa Tenggara chain. Literary works such as the Nagarakretagama (c.1365) list places tied to Majapahit’s orbit, though these reflect a mandala view rather than fixed borders.

Succession disputes, shifting trade patterns, and the rise of Islamic port-states contributed to its fragmentation by the early 16th century.

Islamic sultanates: Demak, Aceh, Banten (15th–18th c.)

Islam spread through merchant networks, scholars, and ports that linked the Indian Ocean to the South China Sea. As Islam took root, sultanates became regional hubs of learning, diplomacy, and maritime power. Demak rose on Java’s north coast in the late 15th and early 16th centuries; Aceh strengthened its hold over northern Sumatra and pepper routes; Banten dominated near the Sunda Strait, channeling spice and pepper trade toward the Indian Ocean world.

These states overlapped in time and differed in regional focus. Demak’s influence in Java intersected with inland dynamics and coastal rivals; Aceh faced contests with Portuguese Malacca and leveraged ties with the Middle East; Banten balanced commerce with evolving relations with European companies. Their rulers drew authority from religious legitimacy and control of ports, while navigating a competitive maritime arena that included Asian and European actors. Their trajectories show how Islamic scholarship, trade, and naval strategy combined to shape politics from the 15th to the 18th centuries.

Dutch and Japanese empires in Indonesia (colonial era and 1942–1945)

From the 17th century, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) created fortified ports, monopolies, and treaties to control the spice trade. This was corporate rule, with the VOC acting as a chartered company that maintained armies and governed territories to protect profits. Over time, VOC authority expanded in key areas but remained focused on revenue extraction through contracts, coercion, and control of shipping lanes.

After the VOC’s dissolution in 1799, the 19th century saw a shift to a formal colonial state. Crown administration consolidated the Dutch East Indies, with significant changes after interludes like the British administration (1811–1816). Policies such as the Cultivation System in the 19th century and later reforms changed labor and land use. Japan’s occupation (1942–1945) dismantled Dutch control, mobilized resources and labor, and reconfigured political realities. After Japan’s surrender, Indonesia proclaimed independence on 17 August 1945, beginning a new era as a republic rather than as part of a European or Japanese empire.

Timeline: Indonesia’s empires and key events

This concise timeline highlights turning points that shaped imperial power in the Indonesian archipelago. It focuses on shifts in maritime control, religious change, and colonial transitions. Dates signal well-known markers, while the actual reach of each polity often fluctuated around these points. Use this as a framework for further reading and to locate “who led what” in relation to sea routes and ports.

- c. 5th–7th centuries: Early polities such as Tarumanagara (West Java) and Kutai (Kalimantan) appear in inscriptions, demonstrating river and port-based authority.

- 7th–13th centuries: Srivijaya, centered on Palembang, dominates the Strait of Malacca; Buddhist scholarship and maritime tolls underpin its wealth.

- 1025: Chola Empire raids Srivijaya’s network, striking Palembang and other nodes; long-term effects weaken centralized control of straits.

- 13th century: Singhasari in East Java precedes Majapahit; Mongol expedition diverted in 1293 becomes part of Majapahit’s origin story.

- 1293–c.1527: Majapahit’s land–sea power peaks in the 14th century under Hayam Wuruk and Gajah Mada, with layered influence across islands.

- 15th–18th centuries: Islamic sultanates take shape; Demak rises in Java; Aceh and Banten become major maritime and pepper hubs.

- 1511: Portuguese capture Malacca, reshaping trade routes and regional rivalries across the straits.

- 1602–1799: VOC era of corporate rule; fortified ports, monopolies, and treaties structure commerce and coastal control.

- 19th century: Crown colonial rule consolidates the Dutch East Indies; administrative reforms and extraction systems define governance.

- 1942–1945: Japanese occupation ends Dutch control; after Japan’s surrender, Indonesia declares independence on 17 August 1945.

Because influence expanded and contracted, any “Indonesia empire map” should be read with attention to date ranges and whether areas shown were cores, tributaries, or allied ports.

Maps and symbols: "Indonesia empire map" and "flag" explained

Searches for “Indonesia empire map” and “Indonesia empire flag” often mix different centuries and polities into one image or label. Maps can help you grasp trade routes and core regions, but they must be read with care. Flags and banners were diverse across kingdoms and sultanates, and there was no single premodern Indonesian flag. The sections below provide practical tips for reading maps, outline historical banners, and explain how to avoid common myths.

What maps can (and cannot) show about imperial reach

Historical maps simplify fluid realities. Mandala-style influence typically fades with distance, so sharp lines on a modern-looking map can be misleading. Good maps differentiate core territories from tributary or allied zones and indicate maritime corridors that mattered as much as inland borders. Because influence changed quickly in response to trade, succession, and conflict, chronology is critical for interpreting any boundary or color shading.

Quick tips for reading an “Indonesia empire map” include: always check the date range; look for a legend distinguishing core control, tributary areas, and maritime routes; examine source notes for the historical basis (inscriptions, chronicles, or later reconstructions); and avoid assuming uniform rule across wide areas. When in doubt, compare multiple maps for the same period to see how historians interpret the same evidence differently.

Banners and flags: from Majapahit to the modern national flag

Premodern polities used diverse banners, ensigns, and emblems that varied by court, regiment, and occasion. Majapahit is often linked to red–white motifs, sometimes described in later tradition as the “gula kelapa” pattern, and to emblems such as the sun-like Surya Majapahit. These elements reflect courtly symbolism rather than a standardized national flag across the archipelago.

While symbolic echoes exist between some historical motifs and the modern flag, they should not be conflated. It is accurate to say there was no single premodern “Indonesian flag,” because there was no single Indonesian empire. Understanding these distinctions prevents anachronistic readings of artwork or banners.

Misuse and myths around "Indonesia empire flag"

Online images labeled “Indonesia empire flag” often reflect modern fan art, composite designs, or misattributed banners. Because different polities coexisted and influenced each other, visual motifs traveled and evolved. Without clear context, it is easy to mistake a regional or regimental emblem for a national precursor that never existed in that form.

To evaluate a claim, apply concise criteria: identify the time period and polity; look for material evidence (textiles, seals, or period illustrations); verify provenance (museum collections, catalog numbers, or excavation records); read the original caption or inscription if available; and cross-check whether the design appears consistently in reliable sources for that specific court and century. These steps help separate historical banners from modern reinterpretations.

- Suggested image alt text: “Map showing Srivijaya and Majapahit spheres in Indonesia.”

- Suggested image alt text: “Historical banners and Indonesia’s modern red–white flag.”

The Chola Empire in Indonesia: what happened in 1025?

In 1025, the Chola Empire from South India launched a naval campaign that targeted Srivijaya’s network across the Malay world. Led by Rajendra I, Chola forces struck key nodes, including Palembang, Srivijaya’s base in Sumatra, and Kadaram (often identified with Kedah), among other sites named in inscriptions. These were maritime raids intended to disrupt control of chokepoints and extract prestige and advantage in the wider Indian Ocean trade.

Evidence for the campaign appears in Chola inscriptions, including records at Thanjavur, which boast of capturing the Srivijayan king and seizing ports. The raids were dramatic but brief. They did not produce a long-term Chola occupation of the archipelago. Instead, they exposed the vulnerabilities of a thalassocracy dependent on control of sea lanes and tribute-bearing ports rather than on an extensive inland bureaucracy.

The longer-term impact was to weaken Srivijaya’s central authority and encourage regional rivals and allies to renegotiate their ties. Over subsequent decades, the balance of power shifted, with other ports and polities asserting greater autonomy. The 1025 campaign thus marks a pivotal moment in the history of the “chola empire in indonesia,” not as a conquest that replaced Srivijaya, but as a shock that accelerated change across straits and coasts.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is there such a thing as a single “Indonesian Empire”?

No, there was no single empire ruling all of Indonesia for all time. Indonesian history includes several major empires and sultanates, notably Srivijaya, Majapahit, and later Islamic states. Each governed different regions and periods. The modern Republic of Indonesia began in 1945.

How far did the Majapahit Empire extend across Indonesia?

Majapahit projected influence across much of today’s Indonesia and parts of the Malay Peninsula in the 14th century. Control varied by region, often through alliances and tribute rather than direct rule. Its core remained in East Java. Peak influence is associated with Gajah Mada and Hayam Wuruk.

Where was the Srivijaya Empire based and why was it important?

Srivijaya was based around Palembang in Sumatra and dominated the Strait of Malacca. It prospered by taxing and securing maritime trade between India and China. It was also a Mahayana Buddhist center that hosted pilgrims and fostered international diplomacy.

What does “Indonesia empire flag” refer to?

Historically, there was no single “Indonesia empire flag” because there was no single Indonesian empire. The modern national flag is red and white. Earlier polities used their own banners (for example, Majapahit motifs), and some modern claims online reflect myths or fan-made designs.

Did the Chola Empire invade parts of Indonesia in 1025?

Yes, the Chola Empire from South India raided Srivijaya in 1025. The campaign struck Palembang and captured the Srivijayan king. Although brief, these raids weakened Srivijaya’s dominance over key trade routes in the long term.

How did Dutch and Japanese empires affect Indonesia’s path to independence?

The Dutch established long-term colonial control that reshaped trade and governance. Japan occupied Indonesia from 1942 to 1945, disrupting Dutch authority and mobilizing resources and labor. After Japan’s surrender in 1945, Indonesia declared independence on August 17, 1945.

Conclusion and next steps

Indonesian history is best understood as a sequence of overlapping empires and sultanates whose power moved with ports, monsoons, and maritime corridors. Srivijaya exemplified a Buddhist thalassocracy anchored at Palembang and the Strait of Malacca, while Majapahit blended Java’s agrarian strength with naval reach across islands. Islamic sultanates later tied religious authority to trade, navigating changing ties with Asian and European actors. Colonial arrangements under the VOC and then the Dutch crown transformed governance and commerce, and Japan’s occupation disrupted that order before the republic’s birth in 1945.

Across these centuries, influence was layered rather than uniform, reflecting the mandala model of a strong core and flexible periphery. Reading an “Indonesia empire map” requires attention to dates, sources, and whether areas shown were cores, tributaries, or maritime routes. The idea of an “Indonesia empire flag” likewise needs context: banners were many and specific to courts, while the modern Merah Putih represents the post-1945 nation-state. With these distinctions in mind, the archipelago’s past appears as a connected oceanic world where trade, diplomacy, and sea power shaped empires and identities.

Your Nearby Location

Your Favorite

Post content

All posting is Free of charge and registration is Not required.