Indonesia Batik: History, Motifs, Regions & How It Is Made

Batik Indonesia is a living art that combines wax-resist techniques, careful dyeing, and storytelling in cloth. Its motifs carry philosophies, social signals, and local identity, while its methods reflect generations of refined craftsmanship. This guide explains what batik is, how it developed, how it is made, key motifs and colors, regional styles, and where to learn more.

What Is Indonesian Batik?

Indonesian batik is a textile made by applying hot wax as a resist on cotton or silk, then dyeing the cloth in stages so that unwaxed areas take color. Artisans draw or stamp patterns with wax, repeat dyeing and fixing cycles to build multiple colors, and finally remove the wax to reveal the design.

- UNESCO recognized Indonesian batik in 2009 on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

- Core centers include Yogyakarta, Surakarta (Solo), and Pekalongan on Java.

- Main techniques: batik tulis (hand-drawn with a canting) and batik cap (patterned with a copper stamp).

- Traditional base fabrics are cotton and silk; the process uses a hot-wax resist.

Printed lookalikes can be beautiful and useful, yet they do not have wax penetration, crackle marks, or the layered color depth that come from the resist-dye method.

Key facts and UNESCO recognition

Indonesian batik was inscribed by UNESCO in 2009 on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. The listing acknowledges a living tradition, including the knowledge of patterning, waxing, dyeing, and social practices around wearing batik. This recognition helped strengthen conservation, education, and cross-generational transmission.

Two core techniques define authentic batik. Batik tulis is hand-drawn with a canting (a small spouted tool), producing fine lines and subtle variations that show the maker’s hand. Batik cap uses a copper stamp to apply wax for repeating motifs, which increases speed and consistency. Both methods create real batik because they use wax-resist. Printed textiles that imitate batik patterns do not use wax and typically show color only on one side; they are distinct products.

Why batik symbolizes Indonesia’s identity

Batik is worn at national ceremonies, formal events, offices, and daily life across many Indonesian regions. While rooted strongly in the Javanese courts of Yogyakarta and Surakarta (Solo), batik has been adopted and adapted by communities throughout the archipelago. This diversity means there is no single “correct” look; instead, styles reflect local histories and materials.

The symbolism of common motifs is accessible and ethical in tone. Designs often encode values such as balance, perseverance, humility, and mutual respect. For example, the repetition and order in certain patterns suggest disciplined living, while flowing diagonals imply steady effort. Beyond symbolism, batik supports livelihoods through micro and small enterprises, employing artisans, dyers, traders, designers, and retailers whose work keeps regional identities alive.

History and Heritage Timeline

The sejarah batik di Indonesia (history of batik in Indonesia) spans courts, ports, and contemporary studios. Techniques matured in the royal courts (kraton) of Yogyakarta and Surakarta (Solo), then spread through trade, urban workshops, and education. Over time, materials shifted from natural to synthetic dyes, and production scaled from household units to integrated value chains. After 2009, cultural recognition encouraged renewed pride and formal training programs.

While the widest documentation comes from Java, related resist-dye traditions appear across Southeast Asia. Interactions with traders from China, India, the Middle East, and Europe introduced new motifs, colorants, and markets. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, batik was both a symbol of refined etiquette and a dynamic craft industry, evolving with tools like the copper cap stamp and modern dyes.

Court origins to wider society

Batik developed within the Javanese royal courts of Yogyakarta and Surakarta (Solo), where refined aesthetics and strict etiquette shaped pattern selection. During the late 18th to 19th centuries (approximate period), certain motifs were closely associated with nobility, and wearing them could signal rank and role. Court workshops set standards for proportion, color harmony, and ceremonial use.

From the 19th to early 20th century (approximate period), batik moved into wider society through trade networks, urban workshops, and education. Merchants and artisans of diverse backgrounds influenced patterns and palettes, especially along the north coast. As towns grew, batik became more available beyond court circles, and its uses expanded from ritual to fashion, commerce, and everyday wear.

Techniques and industry milestones (cap, synthetic dyes)

The copper stamp, known as cap, appeared by the mid-19th century (approximate dating) and transformed production. Repeating motifs could be waxed quickly and consistently, lowering costs and lead times. This enabled larger orders for markets and uniforms. Hand-drawn detailing (tulis) remained important for fine work, but cap made patterned backgrounds faster and more accessible.

In the early 20th century, synthetic dyes—initially aniline families and later other classes—expanded color range and improved consistency compared with some natural sources. These dyes, combined with standardized auxiliaries, reduced batch-to-batch variation and shortened processing time. Cottage industries scaled alongside urban workshops, and exporters connected batik to regional and international buyers. After UNESCO’s 2009 recognition, branding, training, and school programs further supported quality, heritage education, and market growth.

How Batik Is Made (Step-by-Step)

The batik process is a controlled cycle of waxing and dyeing that builds colors layer by layer. Makers select fabric and tools, apply a hot-wax resist to protect areas from dye, and repeat dye baths to achieve complex palettes. Finishing steps remove wax and reveal crisp lines, layered hues, and, sometimes, delicate crackle effects.

- Pre-wash and prepare fabric for even dye uptake.

- Draw or stamp motifs with hot wax (tulis or cap).

- Dye in the first color bath; rinse and fix.

- Reapply wax to protect earlier colors; repeat dyeing and fixing.

- Remove wax (pelorodan) and clean the cloth.

- Finish by stretching, ironing, and quality checking.

Simple pieces may require two or three cycles. Complex batik can involve multiple waxing passes, several dye classes, and careful timing for mordants and fixers. Quality depends on even color penetration, steady line work, and clear motif geometry.

Materials and tools (fabric tiers, wax, canting, cap)

Batik commonly uses cotton or silk. In Indonesia, cotton is often graded by local tiers such as primissima (very fine, smooth hand, high thread count) and prima (fine, slightly lower thread count). These terms help buyers understand fabric density and surface. Silk allows vivid colors and a soft drape but requires careful handling and gentle detergents during finishing.

Wax blends balance flow, adhesion, and “crackle.” Beeswax provides flexibility and good adhesion; paraffin increases brittleness for crackle effects; damar (a natural resin) can adjust hardness and shine. The canting is a small copper tool with a reservoir and spout (nib), available in various sizes for lines and dots. Caps are copper stamps used for repeating motifs, often combined with tulis detailing. Dyes may be natural or synthetic; auxiliaries include mordants and fixers. Basic safety includes good ventilation, a stable heat source (often a wax pot or double boiler), protective clothing, and careful handling of hot wax and chemicals.

The resist-dye cycle (waxing, dyeing, fixing, removal)

The typical flow includes standardized steps: pre-wash, patterning, waxing, dyeing, fixing, repeating cycles, wax removal (pelorodan), and finishing. Artisans protect the lightest areas first, then move to darker shades, adding wax layers to preserve earlier colors. Crackle patterns arise when cooled wax forms micro-fissures that admit small amounts of dye, creating fine veining that some makers prize.

Simple batik may require two to four cycles; intricate work can involve five to eight or more, depending on color count and motif complexity. Local terms are useful for clarity: canting (hand-drawing tool), cap (copper stamp), and pelorodan (wax-removal stage, traditionally by hot water). Quality is judged by even color penetration on both sides, clean line work without spreading, and accurate motif alignment. Consistent fixing—using appropriate mordants or setting agents—ensures durability and colorfastness.

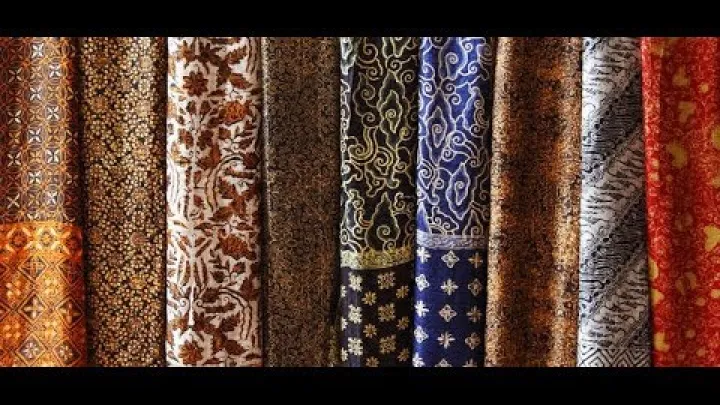

Regional Styles and Centers

Indonesia’s batik landscape includes inland court styles and coastal trade styles that sometimes overlap. Kraton (court) aesthetics from Yogyakarta and Surakarta (Solo) emphasize restraint, order, and ceremonial use. Pesisiran (coastal) traditions in places like Pekalongan, Lasem, and Cirebon reflect maritime trade and cosmopolitan influences, often with brighter palettes and floral or marine motifs.

Modern makers frequently blend elements, so inland vs coastal batik styles are not rigid categories. A single piece can mix structured geometry with radiant colors, or pair classic soga browns with contemporary accents.

Inland (kraton) vs coastal (pesisiran)

Inland styles, associated with kraton (royal court) culture in Yogyakarta and Surakarta (Solo), often use soga browns, indigo, and white. Motifs tend to be orderly and geometric, suitable for rites and formal dress. Their measured palettes and balanced compositions convey dignity and restraint. These textiles historically signaled social roles and were used in court ceremonies.

Coastal or pesisiran batik, seen in Pekalongan, Lasem, and Cirebon, embraces brighter colors and motifs touched by global trade—florals, birds, and marine imagery. Access to imported dyes and exposure to foreign patterns expanded possibilities. Today, designers create hybrids that combine inland geometry with coastal color. This blending reflects Indonesia’s diverse communities and modern tastes.

Highlights: Solo (Surakarta), Yogyakarta, Pekalongan

Surakarta (Solo) is known for refined classics such as Parang and Kawung. Availability of tours and conservation schedules can vary by season and holiday periods, so it is wise to check ahead.

Yogyakarta’s batik often features strong contrasts and ceremonial patterns linked to court traditions. Pekalongan showcases pesisiran diversity and maintains the Museum Batik Pekalongan. Across these cities, visitors can explore workshops, traditional markets, and small studios that provide demonstrations or short classes. Offerings depend on local calendars, so programs may change.

Motifs and Means

Motif batik indonesia covers a wide spectrum, from strict geometry to flowing florals. Two foundational patterns—Kawung and Parang—communicate ethical ideals like balance and perseverance. Colors also carry associations that align with ceremonies and life stages, though meanings vary by region and family tradition.

When reading motifs, focus on shape, rhythm, and direction. Circular or four-lobed repeats suggest balance and centeredness, while diagonal bands imply movement and resolve. Coastal pieces may highlight vivid color stories influenced by trade-era dyes, while inland works lean toward soga browns and indigo for formal settings.

Kawung: symbolism and history

Kawung is a repeating pattern of four-lobed oval forms, arranged in a grid that feels balanced and calm. The shapes are often linked to palm fruit, with an emphasis on purity, order, and ethical responsibility. The clarity of the geometry helps it function well in both formal and everyday contexts.

Historically, Kawung appears in older Indonesian art and reliefs and was once linked to elite circles. Over time, its use widened and adapted to different colorways, from the soga-brown palettes of inland courts to lighter, brighter coastal interpretations. Exact dates and sites can be debated, so it is best to treat those attributions with care.

Parang: symbolism and history

Parang features diagonal, wave-like or blade-like bands that seem to move continuously across the cloth. This diagonal rhythm symbolizes perseverance, strength, and unbroken effort—qualities admired in Javanese thought. The motif’s geometry also makes it suitable for formal garments where strong visual flow is desired.

There are notable variants. Parang Rusak (“broken” or interrupted) shows dynamic energy through segmented diagonals, while Parang Barong is larger in scale and historically associated with high court status. Some variants were once restricted by etiquette within the courts of Yogyakarta and Surakarta (Solo). Traditional versions often use soga browns with indigo and white for formal wear.

Color symbolism in Indonesian batik

Color meanings are best understood as customary tendencies rather than universal rules. Soga browns suggest earth, humility, and stability; indigo signals calm or depth; white conveys purity or new beginnings. Inland court contexts often favor these three in measured combinations, especially for ceremonies and rites of passage.

Coastal palettes are typically brighter, reflecting trade-era dyes and cosmopolitan tastes. Reds, greens, and pastels appear more frequently where imported dyes were accessible. Local customs shape color choices for weddings, births, and memorial events, so meanings can differ by city and family tradition. Always allow for regional nuance.

Economy, Industry, and Tourism

Batik supports a wide value chain that includes artisans, dye specialists, stamp makers, pattern designers, traders, and retailers. Production is largely driven by micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) operating in homes, small studios, or community clusters. These networks supply both domestic shoppers and international buyers who seek batik from Indonesia for apparel, interiors, and gifts.

Employment figures are often estimated in the millions, with some national sources citing around 2.7–2.8 million workers involved across related activities. Export performance fluctuates by year; for example, 2020 exports were reported in the rough range of US$0.5–0.6 billion. The domestic market, however, remains a major driver, with everyday wear and office attire sustaining demand. Tourism hubs like Solo, Yogyakarta, and Pekalongan add museum visits, workshops, and shopping to the experience.

Employment, exports, MSMEs

The batik sector’s employment impact is distributed across many small units rather than a few large factories. This structure helps preserve regional styles and craft autonomy, but it can also make standardization and scaling more complex. Training programs, cooperatives, and design incubators help MSMEs improve quality control and market access.

In terms of trade, export values vary with global demand, currency shifts, and logistics. Figures around US$0.5–0.6 billion were cited for 2020, with subsequent years reflecting recovery patterns. It is important to separate domestic sales from exports because Indonesia’s internal market is significant, especially for school uniforms, office attire, and official ceremonies. These stable channels can cushion external shocks.

Museums and learning (e.g., Danar Hadi, Solo)

Museum Batik Danar Hadi in Surakarta (Solo) is widely known for its extensive historical collection and guided tours that highlight technique and regional variation. In Pekalongan, the Museum Batik Pekalongan provides exhibits and educational programs focused on pesisiran styles. Yogyakarta hosts collections and galleries, including Museum Batik Yogyakarta, where visitors can study tools, fabrics, and patterns up close.

Many workshops in these cities offer demonstrations and short classes that cover waxing, dyeing, and finishing basics. Schedules, conservation rules, and language support may change seasonally or during holidays. It is advisable to confirm opening hours and program availability before planning a visit, especially if you want hands-on learning.

Modern Fashion and Sustainability

Contemporary designers translate batik into workwear, eveningwear, and streetwear while respecting its wax-resist roots. Natural-dye revival, careful sourcing, and repair-friendly construction align batik with slow fashion. At the same time, digital printing allows rapid pattern iteration and experimentation, though it remains distinct from true wax-resist batik.

Sustainability in batik means better dye management, safer chemistry, fair wages, and durable design. Makers balance performance needs with ecological considerations, choosing between natural and synthetic dyes based on colorfastness requirements, supply stability, and client expectations. Clear labeling and craft documentation help consumers make informed choices.

Natural dyes and slow craftsmanship

Natural dyes in Indonesia include indigofera for blues, soga sources for browns, and local woods such as mahogany for warm tones. Hand-drawn batik (tulis) aligns with slow fashion because it is repairable, long-lived, and designed for re-wear. However, natural-dye workflows demand time, consistent supply, and careful testing to manage batch variation and lightfastness.

Basic mordanting and fixing depend on the dye family. Tannin-rich pre-treatments and alum mordants are common for many plant dyes, while indigo relies on reduction chemistry rather than a mordant. For synthetics, fixers vary—soda ash for reactive cotton dyes or specific agents for acid dyes on silk. Natural dyes can be gentler ecologically but may face challenges with consistency; synthetics often provide strong, repeatable shades with shorter lead times. Many studios use a hybrid approach.

Contemporary silhouettes and digital printing

Modern labels rework batik into tailored shirts, relaxed suiting, evening dresses, and streetwear separates. Digital printing enables quick sampling and scale, and some designers combine printed bases with hand-drawn or stamped detailing. This hybrid can balance cost, speed, and artistry while keeping a link to tradition.

It is essential to distinguish genuine batik from patterned textiles. Genuine batik uses wax-resist (tulis or cap) and shows color penetration on both sides, with slight irregularities and possible crackle. Printed fabric has surface-only color and uniform edges. For consumers, check the reverse side, look for tiny line variations, and ask about process. Price and production time can be practical indicators as well.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between batik tulis and batik cap?

Batik tulis is hand-drawn with a canting and shows fine, irregular lines; it takes weeks and is higher priced. Batik cap uses copper stamps for repeating patterns and is faster and more affordable. Many pieces combine cap for background and tulis for detailing. Hand-drawn works often reveal slight line variations and micro-dots at line ends.

Is batik originally from Indonesia or Malaysia?

Batik is most strongly rooted in Indonesia, with deep Javanese court traditions and UNESCO recognition in 2009 as Indonesian Intangible Cultural Heritage. Related resist-dye practices exist in Malaysia and other regions. Today, both countries produce batik, but Indonesia is the primary origin and reference point.

When is National Batik Day in Indonesia?

National Batik Day is on October 2 each year. It commemorates UNESCO’s 2009 inscription of Indonesian batik. Indonesians are encouraged to wear batik on that day and often every Friday. Schools, offices, and public institutions commonly participate.

Where can visitors see authentic Indonesian batik collections?

The Museum Batik Danar Hadi in Solo (Surakarta) houses one of the most comprehensive collections. Other centers include Yogyakarta and Pekalongan, which have museums, workshops, and galleries. Guided tours in these cities often include live demonstrations. Check local museum schedules and conservation rules before visiting.

How do I care for and wash batik fabric?

Wash batik gently by hand in cold water with mild, non-bleach detergent. Avoid wringing; press water out with a towel and dry in shade to protect colors. Iron on low to medium heat on the reverse side, preferably with a cloth barrier. Dry cleaning is safe for delicate silk batik.

What do Kawung and Parang motifs mean?

Kawung symbolizes purity, honesty, and balanced universal energy, historically linked to royal use. Parang represents persistence, strength, and continuous effort, inspired by diagonal “wave-like” forms. Both carry ethical ideals valued in Javanese philosophy. They are widely used in ceremonial and formal contexts.

How can I tell if a batik piece is handmade or printed?

Handmade batik (tulis or cap) usually shows color penetration on both sides and slight line or pattern irregularities. Printed fabric often has sharper, uniform edges, surface-only color, and repeated flaws at exact intervals. Wax crackle marks indicate resist-dyeing. Price and production time are also indicators.

Conclusion and Next Steps

Indonesian batik is both heritage and innovation: a wax-resist craft that carries history, regional identities, and living philosophies. Its timeline runs from kraton refinement to pesisiran vibrancy, its motifs speak through geometry and color, and its industry sustains millions through MSMEs, museums, and modern design. Whether you study its patterns or wear it daily, batik Indonesia remains a durable expression of culture and craft.

Your Nearby Location

Your Favorite

Post content

All posting is Free of charge and registration is Not required.

![Preview image for the video "[ Canting Cap Batik ] – Alat Batik Cap Motif Semarangan". Preview image for the video "[ Canting Cap Batik ] – Alat Batik Cap Motif Semarangan".](/sites/default/files/styles/media_720x405/public/oembed_thumbnails/2025-08/lYrrCzFpYNiHHhQo0lyU8Bkmiuj1oYfUhl-Oa7pz-vI.jpg.webp?itok=Nac9eKk0)