Indonesia Geography: Maps, Facts, Climate, Islands, and Regions

The geography of Indonesia is defined by a vast equatorial archipelago that links the Indian and Pacific Oceans. This setting creates dramatic contrasts: towering volcanoes and deep seas, lush rainforests and seasonal savannas, and rich biodiversity shaped by ancient land bridges and barriers. Understanding Indonesia’s location, islands, climate, and hazards helps travelers, students, and professionals navigate a uniquely maritime nation.

From Sumatra to Papua, landscapes change quickly with tectonics, monsoons, and elevation. The country straddles key biogeographic lines and some of Earth’s busiest sea lanes, making its physical and human geography deeply interconnected.

Quick facts and definition

Indonesia is an archipelagic country in Southeast Asia spanning thousands of islands across the equator. It sits between the Indian and Pacific Oceans and across two continental shelves, which explains its mix of Asian and Australasian species, deep straits, and complex seismic zones.

- Area: about 1.90 million km² of land (figures vary by method).

- Coastline: roughly 54,716 km, among the world’s longest.

- Islands: more than 17,000; about 17,024 officially named as of 2023.

- Highest point: Puncak Jaya (Carstensz Pyramid), 4,884 m, Papua.

- Active volcanoes monitored: around 129.

- Climate: predominantly tropical with monsoonal wet and dry seasons.

- Time zones: WIB (UTC+7), WITA (UTC+8), WIT (UTC+9).

The archipelago spans shallow continental platforms and deep-water gaps. To the west, the Sunda Shelf is a continuation of continental Asia that includes the Java Sea. To the east, the Sahul Shelf is the extension of Australia–New Guinea, evident in the shallow Arafura Sea and Papua’s southern lowlands.

Between these shelves lies Wallacea, a zone of deep straits and island arcs that kept landmasses apart even during ice-age sea-level lows. This geography preserved strong differences in wildlife and shaped human migration, trade routes, and today’s shipping corridors through Malacca, Sunda, Lombok, and Makassar Straits.

Where Indonesia is located (between Indian and Pacific Oceans)

Indonesia stretches across Southeast Asia between the Indian and Pacific Oceans, straddling the equator from roughly 6°N to 11°S and 95°E to 141°E. It borders key semi-enclosed seas such as the Java, Bali, Flores, Banda, Arafura, and Celebes (Sulawesi) Seas, plus strategic straits including Malacca and Sunda.

Geologically, western Indonesia rests on the Sunda Shelf, a broad, shallow extension of mainland Asia. Eastern Indonesia grades toward the Sahul Shelf, which underlies New Guinea and northern Australia. The deep channels that divide these shelves explain both the maritime nature of national integration and the sharp biogeographic boundaries found across the archipelago.

Area, coastline, and island count at a glance

Indonesia’s land area is about 1.90 million km², while its coastline measures around 54,716 km, reflecting the highly indented shores of thousands of islands. Totals vary by survey technique, tidal reference, and updates to official naming, so figures are best read as rounded, widely cited estimates.

The archipelago includes more than 17,000 islands, and as of 2023 about 17,024 have official names in the national gazetteer. Notable superlatives include Puncak Jaya at 4,884 m in Papua and an inventory of roughly 129 monitored active volcanoes. These headline figures summarize a nation where land, sea, and tectonics are closely intertwined.

Location, extent, and maps

Indonesia’s location at the maritime crossroads of Asia and Australia makes its extent and coordinates essential for understanding travel times, climate patterns, and time zones. The country stretches over vast distances that rival intercontinental spans, yet it remains linked by air, sea, and increasingly by digital corridors.

Mapping the archipelago highlights three time zones and major sea lanes that channel global trade. It also shows the interplay between shallow shelves, deep basins, and volcanic arcs that steer ocean currents and shape where people live.

Coordinates, east–west and north–south span

Indonesia’s extreme points illustrate its reach. In the west, Sabang on Weh Island lies near 5.89°N, 95.32°E, while in the east, Merauke in Papua sits near 8.49°S, 140.40°E. The archipelago’s east–west span is about 5,100 km, and its north–south extent is about 1,760 km.

Other significant extremes include Miangas in the north and Rote in the south. The country operates three time zones: WIB (UTC+7) for western Indonesia including Java and Sumatra, WITA (UTC+8) for central regions such as Bali and Sulawesi, and WIT (UTC+9) for Maluku and Papua. These zones align with daily life, transport schedules, and broadcast times.

Exclusive Economic Zone and maritime area overview

Indonesia’s maritime jurisdiction follows international law for archipelagic states. The territorial sea generally extends 12 nautical miles from baselines, the contiguous zone extends 24 nautical miles, and the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) reaches up to 200 nautical miles for resource rights, subject to delimitations with neighbors.

Archipelagic baselines connect outermost islands to enclose internal waters and define sea lanes used by international shipping. Deep-water straits such as Lombok and Makassar provide alternatives to the busy but shallower Malacca route. These passages support the Indonesian Throughflow, which moves warm Pacific waters toward the Indian Ocean and influences regional climate.

Islands and regional structure

Indonesia’s islands are commonly grouped into major regional sets that reflect geology, ecology, and history. The Greater and Lesser Sunda Islands form the core arc from Sumatra through Java to Timor, while Maluku and Western New Guinea extend the nation into the Pacific’s complex island systems.

These regions help explain differences in population density, economic patterns, and biodiversity. They also align with cultural zones and shipping routes that have connected the islands for centuries.

Greater and Lesser Sunda Islands

The Greater Sunda Islands include Sumatra, Java, Borneo (Indonesian Kalimantan), and Sulawesi by common modern convention, while the Lesser Sundas run from Bali east through Lombok, Sumbawa, Flores, Sumba, and Timor. Java concentrates population and agriculture on fertile volcanic soils, with major urban centers such as Jakarta, Bandung, and Surabaya.

The Sunda Arc hosts many active volcanoes from Sumatra through Java and into the Lesser Sundas, shaping landscapes and soils. Eastward, environments transition into Wallacea, a zone where deep channels limited species exchange, producing high endemism in islands such as Sulawesi and Flores.

Maluku and Western New Guinea (Papua)

Maluku spans two provinces, North Maluku and Maluku, with large islands like Halmahera, Seram, and Buru. The region’s seas connect the Pacific and Indian Oceans and frame coral-rich ecosystems amid tectonically complex basins and arcs.

Western New Guinea comprises multiple provinces created or reorganized in 2022–2023: Papua, Central Papua (Papua Tengah), Highland Papua (Papua Pegunungan), South Papua (Papua Selatan), West Papua (Papua Barat), and Southwest Papua (Papua Barat Daya). This region features the Maoke highlands, vast forests, and cultural and biogeographic ties that extend into Oceania.

Physical geography and topography

Indonesia’s relief ranges from glacier-capped peaks to swampy lowlands and coral-fringed coasts. Volcanic arcs produce steep gradients on many islands, while broad peatlands and river plains dominate others. These patterns influence settlement, agriculture, transport, and hazard exposure.

Elevation and aspect also shape local climates. Windward slopes capture moisture, while leeward areas and smaller islands experience stronger dry seasons and thinner soils.

Mountains and highest point (Puncak Jaya, 4,884 m)

The Maoke Mountains in Papua host Puncak Jaya at 4,884 m, one of the world’s few equatorial peaks with persistent ice. These summits are largely non-volcanic, formed by uplift and complex terrane collisions along the northern margin of the Australian Plate.

In contrast, the Bukit Barisan range of Sumatra and the chains across Java and the Lesser Sundas are volcanic, built by subduction along the Sunda Arc. Their cones and calderas create fertile soils, rugged relief, and well-known peaks such as Merapi and Semeru that influence local livelihoods and risks.

| Region or feature | Geologic context | Representative areas |

|---|---|---|

| Sunda Shelf | Shallow continental shelf of Asia | Sumatra, Java, Kalimantan, Java Sea |

| Wallacea | Deep basins and island arcs between shelves | Sulawesi, Nusa Tenggara, parts of Maluku |

| Sahul Shelf | Extension of Australia–New Guinea | Arafura Sea, southern Papua lowlands |

| Sunda Trench | Subduction zone off Sumatra–Java | Source of major earthquakes and tsunamis |

| Banda Arc | Curved collision–subduction system | Maluku and Banda Seas |

Coastal lowlands, plateaus, and elevation gradients

Coastal lowlands and peat swamps are extensive in Kalimantan and parts of Papua, where rivers meander through broad floodplains. These areas support fisheries and transport but face subsidence and flood risk, especially where peatlands have been drained.

By contrast, smaller islands in Nusa Tenggara and parts of Sulawesi show dissected plateaus and steep coastal relief. The North Java Plain is a prominent lowland that hosts dense urban and agricultural belts. Elevation gradients govern land use, from rice paddies in low valleys to coffee and vegetables on cooler uplands.

Tectonics, earthquakes, and volcanoes

Indonesia sits on the meeting zone of the Eurasian, Indo‑Australian, and Pacific Plates. Subduction, collision, and microplate interactions shape the archipelago’s mountains, basins, and frequent seismic activity. Understanding these processes clarifies why Indonesia has so many volcanoes and tsunami-prone coasts.

Risk awareness and monitoring are central to daily life in many regions, particularly along the Sunda Arc and around the complex Banda Sea margins.

Plate boundaries (Eurasian, Indo‑Australian, Pacific)

The Indo‑Australian Plate subducts beneath the Eurasian Plate along the Sunda Trench, generating the volcanic arcs of Sumatra, Java, and the Lesser Sundas. Farther east, the tectonic picture fragments into microplates that rotate, collide, and subduct in different directions.

In the Banda region, subduction polarity varies around a tight arc, and some segments involve arc–continent collision. The Molucca Sea hosts opposing subduction zones that have consumed a small oceanic plate. These settings produce megathrust earthquakes, crustal faulting, and tsunami hazards that require persistent preparedness.

Active volcanoes and historic eruptions

Historic eruptions at Tambora in 1815 and Krakatau in 1883 had global climatic and oceanic impacts.

Primary volcanic hazards include ash fall that disrupts aviation and agriculture, pyroclastic flows that are fast and destructive, lava flows, and lahars (volcanic mudflows) that can be triggered by rain long after eruptions end. Hazard zoning, early warning, and community drills underpin risk reduction in many districts.

Climate and monsoons

Indonesia’s climate is broadly tropical, with wet and dry seasons shaped by shifting winds, ocean temperatures, and topography. The country’s span across the equator and wide elevation range produce local variations that matter for farming, travel, and water planning.

Two ocean–atmosphere patterns, the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD), modulate rainfall from year to year, sometimes amplifying droughts or floods.

Wet and dry seasons and the ITCZ

Most regions experience a dry season from June to September and a wet season from December to March, with April and October as transition months. This cycle reflects the seasonal migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) and associated monsoon circulations.

Regional exceptions are notable. Parts of Maluku and the Banda Sea islands peak in rainfall around mid-year, the inverse of Java’s pattern. ENSO warm phases (El Niño) tend to suppress rainfall over much of Indonesia, while certain IOD configurations can intensify dryness or enhance rains depending on the season.

Rainfall patterns and orographic effects

Orographic uplift drives heavy rain on windward slopes, with annual totals often exceeding 3,000 mm along Sumatra’s Barisan range and in parts of the Papua highlands, where some sites surpass 5,000 mm. Java and Kalimantan commonly receive 1,500–3,000 mm depending on location and elevation.

Moving east across Nusa Tenggara, a pronounced rain shadow reduces annual totals to around 600–1,500 mm, producing seasonal savanna landscapes. Cities create urban heat islands and microclimates that can alter local rainfall timing and intensity, a factor in stormwater planning for Jakarta, Makassar, and other growing metros.

Biodiversity and biogeographical boundaries

Indonesia is a global biodiversity hotspot shaped by deep seaways, shifting land connections, and rapid tectonics. Its islands host combinations of Asian and Australasian species, along with uniquely evolved endemics that define conservation priorities.

Marine ecosystems are exceptionally rich, and mangroves, seagrass beds, and coral reefs underpin coastal livelihoods while buffering storms and erosion.

Wallace Line and Wallacea

The Wallace Line traces deep straits that separate Asian and Australasian fauna. It runs between Borneo–Sulawesi and between Bali–Lombok, where waters remained deep even during ice-age lows, preventing land bridges and preserving distinct evolutionary histories.

Wallacea, the transitional zone between the Sunda and Sahul shelves, holds high endemism because islands were isolated by deep channels. This pattern guides conservation, focusing attention on places like Sulawesi, the Nusa Tenggara islands, and the northern Maluku archipelagos where many species occur nowhere else.

Coral Triangle and marine ecosystems

Indonesia sits at the heart of the Coral Triangle, home to the planet’s highest coral and reef-fish diversity.

Key coastal habitats are coral reefs, seagrass meadows, and mangroves that sequester carbon and sustain fisheries. Pressures include bleaching during marine heatwaves and overfishing, while marine protected areas continue to expand to safeguard biodiversity and livelihoods.

Major islands and regional characteristics

Each major island region has distinct terrain, resources, and settlement patterns. Java’s dense urban corridors contrast with sparsely populated forests of Papua, while Kalimantan’s peatlands differ sharply from Sulawesi’s rugged peninsulas and deep bays.

These differences shape agriculture, industry, and transport—from rice on Java’s plains to mining hubs in Sulawesi and Papua, and from plantation belts in Sumatra to tourism clusters in Bali and Komodo.

Java and Sumatra

Sumatra features the Bukit Barisan mountain chain, broad river systems, and extensive rainforests. Key commodities include palm oil, rubber, coffee, and energy resources. Both islands lie along the active Sunda Arc, balancing the benefits of volcanic soils with recurrent seismic and volcanic hazards.

Kalimantan (Borneo) and Sulawesi

Kalimantan’s interior is characterized by low-relief terrain, peatlands, and large river basins such as the Kapuas and Mahakam. Some watersheds, including the Sembakung and Sesayap, have transboundary catchments with Malaysia and Brunei. Notable protected areas include Tanjung Puting, Kayan Mentarang, and Betung Kerihun.

Sulawesi’s distinctive K-shaped peninsulas and deep surrounding seas foster high endemism and varied coasts. Protected areas such as Lore Lindu, Bunaken, and the Togean Islands highlight terrestrial and marine diversity. The planned national capital, Nusantara, in East Kalimantan is reshaping regional infrastructure and land-use planning.

Papua, Maluku, and the Lesser Sundas

Papua holds the country’s highest mountains, remaining equatorial ice, and vast forest cover with low overall population density. Provincial reorganization since 2022 created new units to improve administration across large, diverse landscapes.

Maluku comprises dispersed archipelagos set within a complex tectonic environment, and the Lesser Sundas display a west–east aridity gradient with iconic islands such as Komodo and Rinca. These regions mix fishing, smallholder agriculture, and growing tourism tied to reefs, volcanoes, and unique wildlife.

Rivers, lakes, and surrounding seas

Indonesia’s rivers knit interior landscapes to coasts, carrying sediments that build deltas and nourish mangroves. Lakes add freshwater fisheries and climate moderation, while surrounding seas shape trade routes, monsoon patterns, and marine livelihoods.

Understanding island-by-island hydrology and adjacent seas helps explain regional economies and environmental risks, from peatland drainage to coastal erosion.

Key rivers by island

Sumatra’s Musi (about 750 km) and Batang Hari (about 800 km) drain mountain flanks to lowland deltas. In Kalimantan, the Kapuas (about 1,143 km) and Mahakam (about 920 km) support transport, freshwater fisheries, and peat–swamp ecosystems.

Java’s rivers are shorter and more seasonal due to steep gradients and narrower plains, while Sulawesi’s Saddang is regionally significant despite its modest length (roughly 180–200 km). Papua’s Mamberamo, near 800 km, drains vast forested basins with high runoff.

| Island | Principal rivers (approx. length) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sumatra | Musi (~750 km), Batang Hari (~800 km) | Deltaic lowlands, transport corridors |

| Kalimantan | Kapuas (~1,143 km), Mahakam (~920 km) | Peatlands, freshwater fisheries |

| Java | Brantas, Citarum (shorter, seasonal) | Irrigation-intensive basins |

| Sulawesi | Saddang (~180–200 km) | Hydropower and irrigation roles |

| Papua | Mamberamo (~800 km) | High discharge, forested catchments |

Lake Toba and Lake Tempe

Lake Toba in Sumatra is a supervolcanic caldera formed by a massive eruption tens of thousands of years ago. Samosir Island rises within the lake, creating a dramatic landscape that moderates local climate and supports tourism and fisheries.

Lake Tempe in South Sulawesi is shallow and expands seasonally with rainfall and river inflow. It formed through fluvial and lacustrine processes in a low-lying basin, and its size and productivity vary with the monsoon, sustaining floating-house communities and wetland biodiversity.

Important seas and straits

Indonesia borders or encloses the Java, Bali, Flores, Banda, Arafura, and Celebes (Sulawesi) Seas, among others. Strategic straits include Malacca, Sunda, Lombok, and Makassar, which link global shipping routes and regional trade hubs.

The Indonesian Throughflow carries warm water from the western Pacific to the Indian Ocean via passages such as Makassar and Lombok Straits. Lombok and Makassar provide deep-water alternatives to the busy Malacca route, shaping maritime logistics and ocean heat exchange.

Natural resources, economy, and environmental risks

Natural resources are distributed across islands and shelves, aligning with ports and straits that connect Indonesia to regional and global markets. This geography supports energy exports, metal mining, agriculture, and fisheries.

At the same time, land conversion, peat drainage, and geological hazards create environmental risks that require careful management alongside economic development.

Energy, mining, and agriculture

Indonesia’s resource base includes coal, natural gas, nickel, tin, gold, and bauxite. Nickel mining has expanded in Sulawesi and Maluku, while hydrocarbons remain important in Sumatra, Kalimantan, and offshore fields. Processing clusters often develop near deep-water ports along major straits.

Agriculture spans rice, oil palm, rubber, cocoa, coffee, and diversified fisheries. Sustainability challenges include deforestation linked to land conversion, peat oxidation and subsidence, tailings and acid drainage from mines, and methane emissions from flooded rice fields. Balancing commodity production with watershed and coastal protection remains a central task.

Deforestation, floods, landslides, and tsunamis

Deforestation is driven by land-use change, infrastructure expansion, and peatland drainage. Peat fires differ from forest canopy fires: they smolder underground, emit dense haze, and are difficult to extinguish, especially during droughts.

Monsoon rains bring floods in lowlands and landslides on steep terrain, while active volcanoes pose lahar hazards during downpours. Tsunami risk is elevated along the subduction zones and outer-arc faults from Sumatra to the Banda Arc, where coastal planning and early warning systems are especially important.

Human geography and administrative regions

Indonesia’s human geography mirrors its physical diversity. Dense urban belts on Java contrast with sparsely populated interiors in Kalimantan and Papua. Inter-island migration and coastal corridors connect labor, markets, and services across long distances.

Administrative units structure governance and resource management, shaping how education, health, transport, and environmental programs are delivered to island communities.

Provinces and population distribution

Population density is highest on Java, home to large metropolitan areas, while outer islands generally have lower densities with concentrations around coasts and river deltas.

Special designations include Aceh (Special Region), the Special Region of Yogyakarta, and the Special Capital Region of Jakarta. These statuses reflect historical, cultural, and administrative arrangements. Urban agglomerations such as Greater Jakarta and Greater Surabaya influence inter-island migration and service corridors.

Urbanization and land use

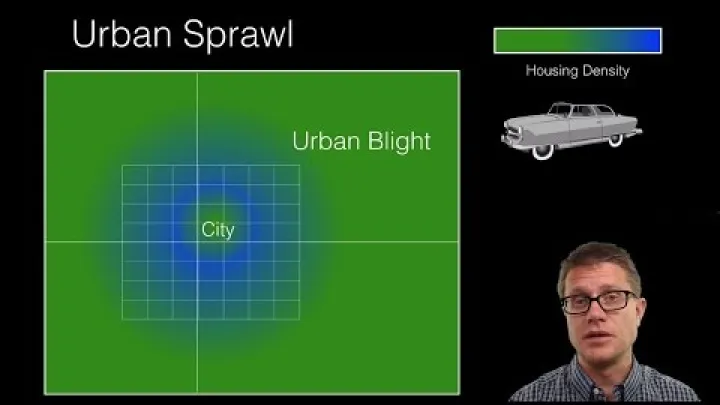

Rapid urban growth shapes coastal corridors, especially on Java, Sumatra’s east coast, and parts of Sulawesi. Official urban areas are defined by administrative and statistical criteria, while peri-urban sprawl extends beyond boundaries with mixed land uses and infrastructure gaps.

Land use blends irrigated agriculture, plantations, forestry, mining, and expanding peri-urban zones.

Frequently Asked Questions

Where is Indonesia located and which oceans border it?

It spans roughly 6°N–11°S latitude and 95°E–141°E longitude, bridging Asia and Australia. Its seas include the Java, Bali, Flores, Banda, and Arafura Seas. Strategic straits include Malacca, Makassar, and Lombok.

How many islands are in Indonesia?

Indonesia has more than 17,000 islands. As of 2023, 17,024 islands have official names in the national gazetteer, with totals varying by survey and tidal definitions. Large islands include Sumatra, Java, Borneo (Kalimantan), Sulawesi, and New Guinea (Papua).

Is Indonesia in Asia or Oceania?

Indonesia is primarily in Southeast Asia, but its Papua provinces are on the island of New Guinea, which is part of Oceania. Geographically it spans the Asian (Sunda Shelf) and Australasian (Sahul Shelf) realms. Politically, Indonesia is classified as an Asian country.

What is the highest mountain in Indonesia?

Puncak Jaya (Carstensz Pyramid) in Papua is the highest mountain at 4,884 meters. It is part of the Maoke Mountains and is one of the world’s few equatorial peaks with permanent snowfields. It forms part of the Oceania Seven Summits list.

How many active volcanoes does Indonesia have?

Indonesia monitors about 129 active volcanoes, the most of any country. Significant historical eruptions include Tambora (1815) and Krakatau (1883). Millions live within volcanic hazard zones, so monitoring and preparedness are continuous.

When are the wet and dry seasons in Indonesia?

The dry season is typically June to September, and the wet season is December to March. April and October are transition months as the Intertropical Convergence Zone shifts. Local relief and monsoon patterns cause regional differences in rainfall timing.

What is the Wallace Line in Indonesia?

The Wallace Line is a biogeographical boundary separating Asian and Australasian species. It runs between Borneo–Sulawesi and Bali–Lombok, tracing deep-water straits that remained barriers during past low sea levels. The transitional region between is called Wallacea.

How many provinces does Indonesia have?

Indonesia has 38 provinces. Several new provinces were created in Papua in 2022–2023, increasing the total from 34 to 38. Provinces are grouped into major island regions such as Java, Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, Maluku, and Papua.

Conclusion and next steps

Indonesia’s geography blends a vast maritime setting with active tectonics, diverse climates, and exceptional biodiversity. The country spans the Sunda and Sahul shelves, with deep straits that define distinct ecological zones and global sea lanes. Volcanic arcs create fertile soils and iconic landscapes, while also imposing seismic and eruption risks that shape settlement and infrastructure.

Regional contrasts are strong: Java’s dense urban belts differ from Kalimantan’s peat-rich interiors and Papua’s high mountains and forests. Seasonal monsoons and orographic effects produce varied rainfall patterns that guide agriculture and water planning. Rivers, lakes, and surrounding seas connect interior basins to coasts, supporting fisheries and trade.

Human geography reflects these physical foundations. Thirty-eight provinces manage diverse environments and resources, from nickel and gas to rice and coffee, amid ongoing efforts to protect forests, reefs, and mangroves. Understanding location, landforms, climate, and hazards provides a clear frame for studying Indonesia and for planning travel, research, or relocation across the archipelago.

Your Nearby Location

Your Favorite

Post content

All posting is Free of charge and registration is Not required.