Indonesia Colonization: Dutch Rule, Timeline, Causes, and Legacy

Indonesia colonization unfolded over three centuries, beginning with the Dutch VOC in 1602 and ending with Dutch recognition of Indonesian sovereignty in 1949. The process combined commerce, conquest, and shifting policies. This guide explains the timeline, systems of rule, major wars, and legacies that still matter today.

Quick answer: when and how Indonesia was colonized

Dates and definition in 40 words

Dutch colonization of Indonesia began with the VOC charter in 1602, shifted to direct state rule in 1800, ended de facto in 1942 with Japanese occupation, and was recognized de jure in December 1949 after revolution and negotiations.

Before colonization, the archipelago was a mosaic of sultanates and port cities tied to Indian Ocean trade. Dutch power grew through monopolies, treaties, wars, and administration, expanding from spice islands to broader territories and export economies across the islands.

Key facts at a glance (bullets)

These quick facts help place the Indonesia colonization timeline in context and clarify what ended Dutch rule in Indonesia.

- Key dates: 1602, 1800, 1830, 1870, 1901, 1942, 1945, 1949.

- Main systems: VOC monopoly, Cultivation System, Liberal concessions, Ethical Policy.

- Major conflicts: Java War, Aceh War, Indonesian National Revolution.

- Outcome: Independence proclaimed 17 August 1945; Dutch recognition on 27 December 1949.

- Before colonization: diverse sultanates linked to global spice and Muslim trade networks.

- Drivers: control of spices, later cash crops, minerals, and strategic sea routes.

- End of rule: Japanese occupation broke Dutch control; UN and U.S. pressure forced negotiations.

- Legacy: export dependence, regional inequality, and a strong nationalist identity.

Together, these points trace how the Dutch colonization of Indonesia evolved from company monopolies to state rule, and how wartime disruption and a mass revolution yielded independence.

Timeline of colonization and independence

The Indonesia colonization timeline follows five overlapping phases: VOC company rule, early state consolidation, liberal expansion, Ethical Policy reforms, and the crisis years of occupation and revolution. Dates mark shifts in institutions and methods, but local experiences varied widely by region and community. Use the table and the detailed period summaries below to connect key events with causes and outcomes.

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 1602 | VOC chartered; start of Dutch commercial empire in Asia |

| 1619 | Batavia founded as VOC hub |

| 1800 | VOC dissolved; Dutch East Indies under state rule |

| 1830 | Cultivation System begins on Java |

| 1870 | Agrarian Law opens land leases to private capital |

| 1901 | Ethical Policy announced |

| 1942 | Japanese occupation ends Dutch administration |

| 1945–1949 | Proclamation, revolution, and sovereignty transfer |

1602–1799: VOC monopoly era

The Dutch East India Company (VOC), chartered in 1602, used fortified ports and contracts to control the spice trade. Batavia (Jakarta), founded by Jan Pieterszoon Coen in 1619, became the company’s Asian headquarters. From there, the VOC enforced monopolies on nutmeg, cloves, and mace through exclusive treaties, naval blockades, and punitive expeditions. Notoriously, the Banda Islands massacre in 1621 aimed to secure nutmeg supply.

Monopoly tools included compulsory delivery contracts with local rulers and hongi patrols—armed voyages to destroy unauthorized spice trees and interdict smugglers. While profits funded forts and fleets, endemic corruption, high military costs, and British competition undermined returns. By 1799, the debt-ridden VOC was dissolved, and its territories passed to the Dutch state.

1800–1870: State control and Cultivation System

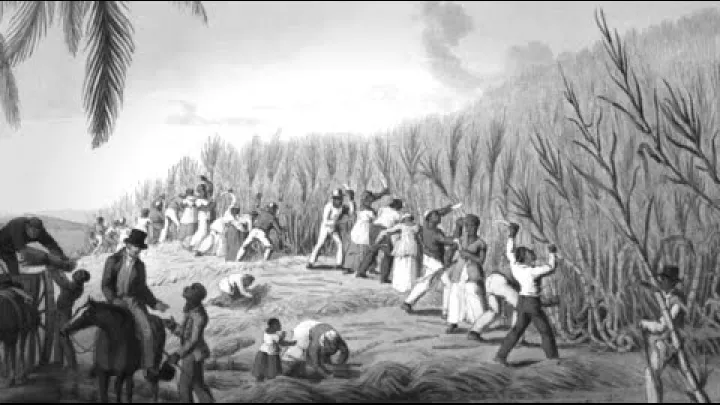

With the VOC dissolved, the Dutch state ruled the Dutch East Indies from 1800. Following wars and administrative reforms, the government sought reliable revenue after the Napoleonic period. The Cultivation System, launched in 1830, required villages—especially on Java—to devote about 20% of land, or equivalent labor, to export crops such as coffee and sugar, delivered at fixed prices.

Implementation relied on local elites—the priyayi and village heads—who enforced quotas and could coerce compliance. Revenues from coffee and sugar were large and helped Dutch public finances, but the system displaced rice fields, deepened food insecurity, and contributed to periodic famine. Criticism grew over abuses, unequal burdens centered on Java, and fiscal dependence on forced cultivation.

1870–1900: Liberal expansion and Aceh War

The Agrarian Law of 1870 opened long leases to private and foreign firms, attracting investment into estates producing tobacco, tea, sugar, and later rubber. Infrastructure—railways, roads, ports, and telegraphs—expanded to connect plantation zones with export corridors and global markets. Regions like Deli in East Sumatra became well-known plantation clusters employing migrant and contract labor.

At the same time, conquest intensified beyond Java. The Aceh War, begun in 1873, dragged on for decades as Acehnese forces adopted guerrilla tactics against Dutch campaigns. High military costs, along with global price swings for estate crops, shaped colonial policy and budget priorities during this era of liberal economic ideology and territorial consolidation.

1901–1942: Ethical Policy and national awakening

Announced in 1901, the Ethical Policy aimed to improve welfare through education, irrigation, and limited resettlement (transmigration). School enrollment expanded and produced a growing educated stratum. Associations such as Budi Utomo (1908) and Sarekat Islam (1912) emerged, while a livelier press circulated ideas that challenged colonial authority.

Despite stated welfare goals, budgets and paternalistic frameworks limited reach and left core extractive structures intact. Nationalist thought spread through organizations and newspapers even as surveillance and press controls persisted.

1942–1949: Japanese occupation and independence

The Japanese occupation in 1942 ended Dutch administration and mobilized Indonesians through new bodies, including PETA (a volunteer defense force), while imposing harsh forced labor (romusha). Occupation policies eroded colonial hierarchies and altered political realities across the archipelago.

The Indonesian National Revolution followed, marked by diplomacy and conflict. The Dutch conducted two “police actions” in 1947 and 1948, but UN involvement and U.S. pressure steered negotiations toward the Round Table Conference. The Netherlands recognized Indonesian sovereignty in December 1949, distinguishing de facto change in 1942 from the de jure transfer in 1949.

Phases of Dutch rule explained

Understanding how Dutch colonization of Indonesia evolved helps explain changing policies and their uneven effects. Company monopolies gave way to state rule, then to private concessions under liberal ideas, and finally to a reformist posture that coexisted with control. Each phase shaped labor, land, mobility, and political life in different ways.

VOC control, spice monopolies, and Batavia

Batavia anchored VOC authority as an administrative and commercial center linking Asia and Europe. Jan Pieterszoon Coen’s aggressive strategy sought to dominate the spice trade by concentrating power in strategic ports, compelling suppliers into exclusive agreements, and punishing defiance. This system reconfigured local politics, forging alliances with some rulers while warring with others.

Monopolies relied on naval blockades, convoy systems, and punitive expeditions that enforced delivery and suppressed smuggling. Some polities retained partial autonomy in exchange for cooperation, but the costs of wars, ship maintenance, and garrisons grew. Profit financed expansion, yet inefficiency, corruption, and rising competition produced mounting debts that culminated in the VOC’s collapse.

Cultivation System: quotas, labor, and revenue

The Cultivation System typically required villages to allocate about 20% of land—or equivalent labor—to cash crops. Coffee, sugar, indigo, and other commodities were delivered at fixed prices, generating revenue that became central to Dutch metropolitan budgets.

Local intermediaries were pivotal. The priyayi and village heads managed quotas, labor rosters, and transport, which enabled coercion and widespread abuses. As export plots spread, rice fields shrank or lost labor time, increasing food insecurity. Critics connected periodic famines and rural hardship to the system’s design and its focus on revenue over subsistence.

Liberal era: private plantations and railways

Legal changes allowed firms to lease land long term for estates producing tobacco, tea, rubber, and sugar. Railways and improved ports linked plantation districts to export routes, encouraging inter-island migration and expanding wage and contract labor. Deli in East Sumatra became emblematic of plantation capitalism and its strict labor regimes.

Colonial revenues rose with commodity booms, but exposure to global cycles increased volatility. Expanding state power in the outer islands involved both military campaigns and administrative integration. The combination of private investment and public force established new economic geographies that would outlast colonial rule.

Ethical Policy: education, irrigation, and limits

Launched in 1901, the Ethical Policy promised schooling, irrigation, and resettlement to improve welfare. Enrollment gains produced teachers, clerks, and professionals who articulated nationalist goals through associations and the press. Yet budget limits and a paternalistic framework constrained reforms.

Welfare projects coexisted with extractive legal and economic structures, leaving stark inequalities intact. In one sentence: the Ethical Policy expanded education and infrastructure, but uneven funding and control meant that benefits were limited and sometimes reinforced colonial hierarchies.

Wars and resistance that shaped the archipelago

Armed conflicts were central to the making of the Dutch East Indies and to its unmaking. Local grievances, religious leadership, and shifting military strategies all shaped outcomes. These wars left deep social scars and informed administrative, legal, and political changes across the islands.

Java War (1825–1830)

Prince Diponegoro led a broad resistance in central Java against colonial encroachment, land disputes, and perceived injustices. The conflict devastated the region, disrupting trade and agriculture while mobilizing villagers, religious leaders, and local elites on both sides.

Casualty estimates often reach into the hundreds of thousands when including civilians, reflecting the war’s scale and displacement. Diponegoro’s capture and exile ended the conflict and consolidated Dutch control. Lessons from the war informed later administrative reforms and military deployments in Java.

Aceh War (1873–1904)

Disputes over sovereignty, trade routes, and foreign treaties sparked the Aceh War in northern Sumatra. Initial Dutch campaigns assumed quick victory but met organized resistance. As the conflict dragged on, Acehnese forces shifted to guerrilla warfare based on local networks and challenging terrain.

The Dutch adopted fortified lines and mobile units, and drew on advice from scholar Snouck Hurgronje to divide opponents and co-opt elites. Under Governor-General J.B. van Heutsz, operations intensified. The prolonged fighting caused heavy casualties—often numbered well over one hundred thousand—and strained the colonial treasury.

Indonesian National Revolution (1945–1949)

After the 1945 proclamation of independence, Indonesia faced diplomatic struggle and armed confrontation. The Dutch launched two major “police actions” in 1947 and 1948 to retake territory, while Indonesian forces and local militias used mobile warfare and maintained political momentum.

Key agreements—Linggadjati and Renville—failed to resolve core disputes. UN bodies, including the UN Good Offices Committee, and U.S. leverage pushed both sides toward talks. The Round Table Conference produced the transfer of sovereignty in December 1949, concluding the revolution.

Economy and society under colonial rule

Colonial structures prioritized extraction, export corridors, and administrative control. These choices built ports, rails, and plantations that linked islands to global markets but also created vulnerabilities to price swings and reinforced unequal access to land, credit, and education.

Extraction models and export dependence

Colonial budgets relied on export crops and trade taxes to fund administration and military campaigns. Core commodities included sugar, coffee, rubber, tin, and oil. The Bataafsche Petroleum Maatschappij, a key arm of Royal Dutch Shell, illustrates how oil operations integrated Indonesia into global energy markets.

Investment was concentrated in Java and select plantation regions, widening regional gaps. Exposure to global price cycles produced recurring crises that hit workers and smallholders hardest. While infrastructure improved logistics, value often flowed outward through freight, finance, and remittances to metropolitan centers.

Racial-legal hierarchy and intermediaries

A tripartite legal order categorized residents as Europeans, Foreign Orientals, and Natives, each under different laws and rights. Chinese and Arab intermediaries played critical roles in commerce, tax farming, and credit, linking rural producers to urban markets.

Urban segregation and pass rules shaped daily movement and residence. The wijkenstelsel, for example, enforced separate wards for certain groups in some cities. Local elites—the priyayi—mediated governance and resource extraction, balancing local interests with colonial directives.

Education, press, and nationalism

School expansion fostered literacy and new professions, enabling a public sphere of debate.

Press laws constrained speech, but newspapers and pamphlets circulated nationalist and reformist ideas. The 1928 Youth Pledge affirmed unity of people, language, and homeland, signaling that modern education and media were transforming colonial subjects into citizens of a future nation.

Legacies and historical reckoning

The legacies of Dutch colonization include economic patterns, legal frameworks, and contested memories. Recent scholarship and public debates have revisited violence, accountability, and reparations. These discussions inform how Indonesians and Dutch society engage with the past and with archival evidence.

Systematic colonial violence and 2021 findings

Multi-institutional research conducted in the late 2010s and presented publicly around 2021–2022 concluded that violence in 1945–1949 was structural rather than incidental. The program assessed actions across Java, Sumatra, Sulawesi, and other regions, examining both military operations and civilian experiences during the Indonesian National Revolution.

Dutch authorities have acknowledged abuses and issued formal apologies, including a royal apology in 2020 and a government apology in 2022 following the study’s conclusions. Debates continue over memory, compensation, and access to archives, with renewed focus on testimonies from diverse communities.

Long-term economic and social impacts

Export orientation, transport routes, and land tenure patterns persisted after 1949, shaping industrialization and regional development. Java retained administrative and market primacy, Sumatra’s plantation belts remained pivotal for exports, and eastern Indonesia continued to face infrastructure and service gaps.

Education expansion left important gains, but access and quality were uneven. Postcolonial institutions reworked colonial legal frameworks, blending inherited codes with national legislation in courts, land policy, and governance, while addressing center–periphery divides with mixed success.

International context and decolonization

Indonesia’s path to sovereignty unfolded within a wider wave of decolonization. UN involvement, including the UN Good Offices Committee and ceasefire calls, and U.S. leverage over postwar aid influenced Dutch decision-making and timelines.

Early Cold War dynamics shaped diplomatic calculations, yet Indonesia’s struggle resonated across Asia and Africa as an anticolonial model. The combination of mass mobilization, international pressure, and negotiation became a pattern in later decolonization cases.

Frequently Asked Questions

What years was Indonesia under Dutch rule, and what ended it?

Dutch rule began with the VOC in 1602 and state rule in 1800. It ended de facto in 1942 with the Japanese occupation and de jure in December 1949 when the Netherlands recognized Indonesian sovereignty after the revolution, UN pressure, and U.S. leverage.

When did the Dutch colonize Indonesia, and why?

The Dutch arrived in the late 1500s and formalized control with the VOC charter in 1602. They sought profits from spices and, later, cash crops, minerals, and strategic sea routes, competing with European rivals for Asian trade and influence.

What was the Cultivation System in Indonesia and how did it work?

From 1830, villages—especially on Java—had to allocate about 20% of land or labor to export crops like coffee and sugar. Managed by local elites, the system generated large revenues but reduced rice cultivation, worsened food insecurity, and led to abuses.

How did the VOC control the spice trade in Indonesia?

The VOC used exclusive contracts, fortified ports, naval blockades, and punitive expeditions to control cloves, nutmeg, and mace. It enforced supply through hongi patrols and used violence, including the 1621 Banda Islands massacre, to maintain monopoly power.

What happened during the Aceh War and why did it last so long?

The Aceh War (1873–1904) began over sovereignty and trade in northern Sumatra. Dutch forces faced resilient guerrilla resistance. Strategy shifted to fortified lines and selective alliances, but casualties were very high and costs strained the colonial budget.

How did the Japanese occupation change Indonesia’s path to independence?

The 1942–1945 occupation dismantled Dutch administration, mobilized Indonesians, and created mass organizations like PETA. Despite exploitation and forced labor (romusha), it opened political space; Sukarno and Hatta declared independence on 17 August 1945, leading to the revolution and 1949 sovereignty.

What are the main effects of colonization in Indonesia today?

Long-term effects include export dependence, regional inequality, and legal-administrative legacies. Infrastructure built for extraction shaped trade routes, while education expansion created new elites but left uneven access across Java, Sumatra, and eastern Indonesia.

What were the main features of the Ethical Policy (1901–1942)?

The Ethical Policy emphasized irrigation, transmigration, and education to improve welfare. Limited budgets and paternalism constrained outcomes, but expanded schooling helped foster an educated elite that advanced nationalist organization and ideas.

Conclusion and next steps

Indonesia’s colonization moved from VOC monopolies to state extraction, liberal concessions, and reformist rhetoric before wartime collapse and revolution ended Dutch rule. The legacy includes export corridors, legal hierarchies, regional inequalities, and a durable national identity. Understanding these phases clarifies how historical choices still shape Indonesia’s economy, society, and politics.

Your Nearby Location

Your Favorite

Post content

All posting is Free of charge and registration is Not required.