Indonesia Traditional Clothes: Types, Names, Batik, Kebaya, Sarong

From batik and kebaya on Java to ulos in North Sumatra and songket in Palembang and Minangkabau regions, each piece tells a story. This guide explains core techniques and garment types, where they are worn, and how to choose authentic items. It also includes men’s and women’s attire tips, a glossary of names, and practical care advice.

Quick overview and key facts

Traditional clothes in Indonesia blend textile techniques, garment forms, and accessories that vary by region, religion, history, and occasion. While some items are part of daily life, others appear mainly at ceremonies and formal events. Understanding the difference between how a cloth is made and how it is worn clarifies a complex but fascinating heritage.

What 'Indonesia traditional clothes' means

The phrase covers a wide spectrum: hand-produced textiles, distinct garment shapes, and accessories that are rooted in local custom. It includes cloth made by methods such as batik, ikat, songket, ulos, tapis, and Ulap Doyo, as well as clothing forms like kebaya blouses, sarongs, jackets, headgear, and sashes.

It is helpful to separate technique from type. Techniques describe how a fabric is created or decorated (for example, batik uses wax-resist dyeing, ikat ties and dyes yarns before weaving, and songket inserts supplementary wefts). Clothing types describe how fabric is shaped and worn (for example, a kebaya blouse or a sarong wrap). A single garment can combine both, such as a kebaya paired with a batik or songket skirt.

Core techniques: batik, ikat, songket

It is internationally recognized for cultural significance and is strong in Yogyakarta, Surakarta, Pekalongan, Cirebon, and Lasem. Cotton is common, with silk used for formal wear. Ikat ties and dyes yarns before weaving to place patterns in the cloth; it can be warp, weft, or the rare double ikat. It thrives in Bali, Nusa Tenggara, Flores, Sumba, and Timor, often with plant-based dyes on cotton or silk blends.

Songket is a supplementary-weft weave that floats metallic or glossy threads over a base fabric to create shimmering motifs. Key centers include Palembang, Minangkabau areas, Melayu communities, and parts of Lombok. Traditional songket uses silk or fine cotton bases with gold- or silver-colored threads. Each technique has regional signatures, preferred fibers, and characteristic motifs that help identify origin and meaning.

When and where traditional clothes are worn

Traditional attire appears at weddings, religious festivals, state ceremonies, performances, and cultural holidays. Many workplaces, schools, and government offices designate special days—often weekly—for wearing batik or regional dress. In tourism areas, heritage garments are also visible at cultural parks and community showcases, supporting artisans and local identity.

Urban trends lean toward modernized cuts, easier-care fabrics, and mix-and-match styling with Western clothing. Rural customs may preserve stricter combinations and protocol, especially for rites of passage. Institutional uniforms, such as school batik or civil service batik, sit between these worlds by standardizing traditional motifs for everyday use.

Types of Indonesian traditional clothing

Indonesia’s wardrobe includes both specific garments and the textiles used to make or accompany them. Below are cornerstone types you will encounter, with notes on how to recognize them, where they come from, and how they are worn today. Each item carries distinct history and regional variations that shape its look and function.

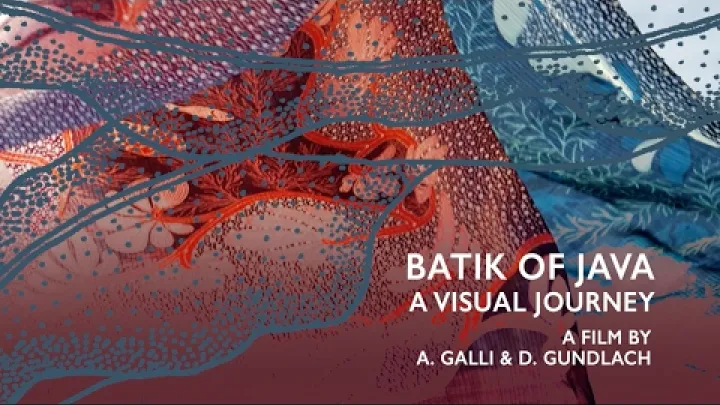

Batik (UNESCO-recognized technique and motifs)

Batik is made by applying wax to cloth to resist dye, then coloring and re-waxing in layers to build patterns. Hand-drawn batik (batik tulis) has organic, slightly irregular lines and usually shows color penetration on both sides. Hand-stamped batik (batik cap) uses repeating stamp blocks; edges are more uniform but still show dye on the reverse. Hybrid pieces combine both methods for efficiency and detail.

To distinguish authentic batik from printed lookalikes, inspect the back: true batik shows design and color through the fabric, while surface printing often looks pale or blank on the reverse. Hand-drawn lines vary subtly in thickness, and wax crackle can appear as fine veins. Motifs such as parang, kawung, and mega mendung carry historical references, and centers like Yogyakarta, Surakarta, Pekalongan, Cirebon, and Lasem are known for signature palettes and styles.

Kebaya (women's blouse and variants)

The kebaya is a fitted, often sheer blouse worn over an inner layer and paired with a batik or songket skirt. Variants include kebaya encim with Peranakan influences, kebaya kartini associated with Central Java’s refined silhouette, and modern versions using lace or tulle. It is widely chosen for ceremonies, formal events, and national occasions.

For international wearers, sizing and tailoring are key. A kebaya should skim the body without pulling at the shoulders or bust, and sleeves should allow comfortable movement. Pair it with a breathable camisole for modesty and comfort, and choose natural fibers when possible in hot climates. Skirts can be secured with ties, hidden zippers, or clip-on closures for easy wear.

Sarong (all-gender tubular wrap)

The sarong is a tubular or lengthwise wrap worn by men and women for daily life and ceremonies. Everyday wear relies on simple folds and rolls, while formal settings may add pleats, belts, or structured waistbands. Fabrics range from batik to plaid (kotak), ikat, or songket, depending on region and occasion.

Not all long cloths are the same: sarong often refers to a sewn tube, while kain panjang (jarik) is a long, unstitched rectangle used in Java with specific tying. In Bali, kamben describes temple wraps, often combined with a selendang sash and udeng headcloth for men. Understanding these distinctions helps you choose the right cloth for the right context.

Ikat (yarn-resist textiles of eastern Indonesia)

Ikat patterns are formed by binding sections of yarn before dyeing, then aligning them during weaving. The technique can be warp, weft, or double ikat, the last requiring meticulous alignment by highly skilled weavers. Strong traditions exist in Bali, Nusa Tenggara, Flores, Sumba, and Timor, often using natural dyes and cotton bases with rich, earthy palettes.

Motifs frequently encode clan or village identity, status, or ritual function. Specific patterns may be reserved for life events, exchanges, or ceremonial leadership, and designs can act as visual signatures of community. If you are collecting or wearing ikat, ask about the motif’s origin and appropriate use to show respect for local knowledge.

Songket (supplementary weft with metallic threads)

Songket adds floating supplementary wefts—often gold or silver-colored—to create lustrous designs over a plain woven base. It is prominent in Palembang, Minangkabau areas, Melayu communities, and parts of Lombok, where it is favored for weddings and high-status ceremonies. The base cloth is usually cotton or silk, with metallic threads forming floral, geometric, or heraldic motifs.

Because metallic threads are delicate, handle songket gently. Avoid sharp folds on areas with floats; roll for storage, and keep it away from moisture, perfumes, and rough surfaces that can snag threads. When in doubt, air and brush lightly rather than wash, and consult specialist cleaners for any stains.

Ulos (Batak ritual cloths)

Ulos are ceremonial textiles central to life-cycle rituals among Batak communities in North Sumatra. Common types include ragidup, sibolang, and ragi hotang, frequently in red–black–white palettes. Ulos are exchanged in the act of mangulosi to convey blessings, strengthen kinship, and mark transitions such as marriage or birth.

Attributions vary across Batak subgroups, including Toba, Karo, Simalungun, Pakpak, Angkola, and Mandailing communities. Patterns, color balances, and contexts of use can differ, so learning local terms improves understanding and respectful use. Many families treasure heirloom ulos that carry lineage memory.

Tapis (Lampung embroidered textiles)

Tapis originates from Lampung and combines techniques such as embroidery, couching, and sometimes supplementary weft over a striped ground. Typical motifs include ships, flora, and geometric forms, and the textiles are traditionally worn as women’s tube skirts during ceremonies.

While both tapis and songket display shimmering elements, their constructions differ. Tapis emphasizes embroidery and couching applied to a woven base, whereas songket builds its designs within the weave as floating supplementary wefts. Recognizing these structural differences helps buyers and students classify textiles accurately.

Baju Bodo (Bugis garment and color codes)

Baju Bodo is a loose, rectangular blouse associated with Bugis-Makassar communities in South Sulawesi, commonly paired with a sarong or silk skirt. Traditionally made from sheer materials, it allows vibrant sarong patterns to show through and is worn for festivals and important family occasions.

Color conventions communicate age and status in some local traditions, but mappings vary by village and family. Contemporary practice embraces wider palettes, and choices may reflect personal taste or event themes. When attending a ceremony, it is courteous to ask hosts about preferred colors and accessories.

Ulap Doyo (Dayak leaf-fiber weaves)

Ulap Doyo textiles are produced by Dayak Benuaq communities in East Kalimantan using fibers from the doyo plant. Artisans process the leaves, spin fibers, and weave cloth decorated with Dayak geometric motifs, often colored with natural pigments and plant dyes.

These non-cotton plant fibers highlight sustainable, locally sourced materials and resilient craft knowledge. Ulap Doyo appears in garments, bags, and ritual items, offering a durable alternative to imported fibers while expressing regional identity and ecological stewardship.

Regional styles across Indonesia

Understanding regional dress helps you read motifs, colors, and silhouettes with greater accuracy. Below are key areas and their hallmark textiles and garments.

Sumatra: songket, ulos, tapis

Sumatra hosts diverse textile traditions. Palembang and Minangkabau centers are renowned for sumptuous songket with metallic threads and courtly floral or geometric designs. In North Sumatra, Batak communities maintain ulos for life-cycle rituals and kinship exchanges, while Lampung is known for tapis tube skirts featuring ship motifs and bold stripes.

Coastal aesthetics often favor high sheen, elaborate patterning, and colors linked to maritime trade and royal courts. Highland areas may prioritize symbolic geometry, tighter weaves, and ritual palettes. Ceremonial use remains strong island-wide, with garments signaling clan ties, marital status, and household prestige.

Java and Madura: batik heartland and court aesthetics

Central Java’s courts in Yogyakarta and Surakarta developed refined batik with soga browns, indigo blues, and structured motifs such as parang and kawung. Coastal batik from Pekalongan, Cirebon, and Lasem showcases brighter palettes and maritime influences, reflecting centuries of trade and cultural exchange. Madura batik is known for bold reds, high contrast, and dynamic, energetic patterns.

Men’s regional dress may include the blangkon headcloth and a beskap jacket paired with a batik jarik. Women often wear kebaya with a batik kain. Protocol, motif choice, and color selection can reflect social standing and event formality, with some patterns historically linked to status or court association.

Bali and Nusa Tenggara: bright palettes and Hindu influence

Bali’s temple attire includes kamben or kain wraps, selendang sashes, and udeng headcloths for men, with dress codes aligned to ritual purity and etiquette. Distinct textiles include Bali endek (weft ikat) and Tenganan’s rare double ikat geringsing, which is highly valued for ritual use. Lombok contributes notable songket with regional motifs and palettes.

It is important to differentiate ceremonial dress from tourist performance costumes, which may exaggerate color or accessories for stage effect. At temples, dress modestly, observe signage, and follow local guidance on sashes and headgear. Visitors are often provided appropriate wraps when required.

Kalimantan and Sulawesi: Dayak and Bugis traditions

Dayak communities across Kalimantan maintain diverse traditions including beadwork, occasional bark cloth in certain areas, and Ulap Doyo weaves from doyo leaf fiber among the Dayak Benuaq. Patterns often reflect local cosmology and environmental motifs, with garments and accessories used in ceremonies and community events.

In South Sulawesi, Bugis-Makassar attire features Baju Bodo with silk sarongs from weaving centers such as Sengkang. Toraja communities in the highlands present distinctive motifs, headgear, and ceremonial ensembles. Attributions should be made carefully to specific groups to avoid broad generalizations.

Symbolism and occasions

Textiles in Indonesia communicate more than style: they signal protection, prosperity, status, and social bonds. Meanings vary by place and time, and many patterns have layered interpretations. The notes below illustrate how colors, motifs, and events shape what people wear.

Colors and motifs: protection, prosperity, status

Motifs such as parang, kawung, and ship designs carry themes of power, balance, and journey. In courtly batik, muted soga tones and refined geometry balance restraint and elegance. In Lampung, ship motifs may refer to travel, migration, or life transitions, while in Sumba and Timor, ikat motifs can encode lineage or spiritual protection.

Color systems vary widely. Batak traditions often use a red–black–white triad linked to life-cycle symbolism, while Central Javanese palettes emphasize browns and blues. Historical sumptuary rules influenced who could wear certain patterns or colors. Meanings are context-dependent and evolve, so local knowledge remains the best guide.

Life events and ceremonies: birth, wedding, mourning

In Batak communities, ulos are bestowed at milestones in an act called mangulosi, strengthening social bonds and offering blessings. Across Sumatra, songket anchors wedding attire, paired with headdresses and jewelry that mark family status and regional identity. In Java, wedding batik motifs such as Sido Mukti express hopes for prosperity and harmonious union.

Mourning attire usually favors subdued palettes and simpler patterns, though specifics differ by region and faith tradition. Urban ceremonies may adapt classical elements into contemporary styling, combining comfort with symbolism while maintaining respectful references to heritage.

Religion and civic life: Islamic dress, Balinese ceremonies, national days

Common items in Muslim communities include baju koko shirts, sarongs, and the peci cap, often combined with modest kebaya ensembles for women. Friday prayers and religious festivals see increased use of these garments, though practices vary by family and locality. Examples are offered here to illustrate patterns rather than prescribe behavior.

Institutions such as schools and government offices may designate special batik days to celebrate heritage.

Men's and women's attire: what to wear and when

Understanding common sets helps visitors and residents dress appropriately for events. Below are typical ensembles for men and women, with practical tips on fit, comfort, and climate. Always confirm local preferences for ceremonies or temple visits.

Men: baju koko, beskap, sarong, peci

Men often wear a baju koko shirt, sarong, and peci for religious gatherings and formal events. In Java, formalwear may include a beskap jacket with a batik jarik and blangkon headgear. In Sumatra, songket jackets or hip cloths appear at weddings, paired with regional accessories.

Fit tips: baju koko should have ease at the shoulders and chest for prayer movements; beskap jackets fit close but should not restrict breathing. Select breathable cotton or silk blends in hot climates, and consider undershirts that wick moisture. If unsure, rental or tailoring services in major cities can help with event-ready ensembles.

- Step into the sarong tube or wrap the long cloth around your waist with the seam at the side or back.

- Pull it to waist height and fold excess cloth inward to fit your waist.

- Roll the top edge down 2–4 times to lock the fold; add one more roll for a tighter hold.

- For movement or formal looks, create a front pleat before rolling, or secure with a belt under a jacket.

Women: kebaya, kemben, batik or songket skirts

Women commonly pair a kebaya top with a batik kain or songket tube skirt. In certain Javanese and Balinese contexts, a kemben (chest wrap) appears under or in place of a blouse, with a selendang sash for accent and ritual use. Hair ornaments and subtle jewelry complete ceremonial looks without overwhelming fine textiles.

For comfort in hot and humid climates, choose breathable fibers (cotton, silk) and light linings. Layering with a camisole or tube top supports modesty while preventing irritation from lace. Skirts can be pre-stitched with zippers or velcro for easy wear; consider anti-slip underskirts to keep fabric drape neat throughout a long event.

Buying guide: how to choose authentic pieces and where to buy

Purchasing traditional clothes supports artisans and preserves heritage when done thoughtfully. Understanding authenticity cues, materials, and fair-trade practices helps you make informed choices and care for items over time. The notes below offer practical checkpoints and sourcing advice.

Authenticity checks and artisan cues

Look for signs of handwork. In hand-drawn batik, lines are slightly irregular, and color penetrates both sides. In hand-stamped batik, the repeat is even but still shows wax-resist character on the reverse. For songket, confirm that metallic designs are true floats woven into the cloth rather than surface printing.

Provenance matters. Seek artisan signatures, cooperative labels, and information on fibers and dyes. Ask makers how long a piece took and what techniques they used; genuine craft often requires many days or weeks. Documentation, photos of the weaving or batik process, and community branding all support authenticity and fair compensation.

- Check the back of the cloth for pattern and color penetration.

- Feel the surface: printed imitations tend to feel flat; real floats and wax-resist add texture.

- Ask about fibers (cotton, silk, doyo, metallic threads) and dye sources.

- Buy from workshops, museum shops, cooperatives, or trusted boutiques that credit makers.

Materials, price ranges, and fair trade considerations

Common materials include cotton for daily wear, silk for formal garments, rayon blends for affordability, doyo leaf fiber in Ulap Doyo, and metallic threads in songket. Prices reflect the amount of handwork, motif complexity, fiber quality, and regional rarity. Expect higher prices for batik tulis, double ikat, and fine songket with dense floats.

For storage and shipping, roll textiles around acid-free tubes, interleave with unbuffered tissue, and avoid tight folds that stress fibers. Keep items dry and away from sunlight; include cedar or lavender to deter pests. When sending internationally, use breathable wrapping inside waterproof outer layers, and declare materials accurately to avoid customs delays.

Care and storage for batik, songket, and delicate textiles

Proper care preserves color, drape, and structure across different Indonesian textiles. Always test for colorfastness in a hidden corner and handle embellishments with care. When in doubt, choose gentle methods and professional advice for complex stains or heirloom pieces.

For batik, hand-wash separately in cool water with mild soap, avoiding bleach and optical brighteners that can strip soga tones. Do not wring; press water out with a towel and dry in shade to protect dyes. Iron on low to medium heat on the reverse side, or use a pressing cloth to protect wax-resist texture.

For songket and metallic-thread textiles, avoid washing unless absolutely necessary. Air garments after wear, brush gently with a soft cloth, and spot clean without saturating floats. Store rolled rather than folded, with tissue barriers to prevent abrasion. Keep away from perfumes, hair sprays, and rough jewelry that can snag threads.

Ikat, ulos, and other naturally dyed pieces benefit from minimal washing, shade drying, and limited exposure to strong light. For all textiles, maintain stable humidity and temperature, and use breathable storage materials. Inspect seasonally for pests or moisture. With thoughtful care, textiles can remain vibrant for generations.

Glossary: names of Indonesia traditional clothes (A–Z list)

This alphabetical list explains common names of traditional clothes in Indonesia. Terms vary by region and language; local usage is the best guide. Use these concise definitions to navigate markets, museums, and ceremonies with confidence.

- Baju Bodo: Rectangular, sheer blouse from Bugis-Makassar communities, worn with a sarong.

- Baju Koko: Collarless men’s shirt commonly worn with a sarong and peci.

- Batik: Wax-resist dyed cloth; includes hand-drawn (tulis) and hand-stamped (cap) methods.

- Beskap: Structured men’s jacket in Javanese formal dress, often paired with batik jarik.

- Blangkon: Javanese men’s headgear made from folded batik cloth.

- Endek: Balinese weft ikat textile used for skirts and ceremonial wear.

- Geringsing: Rare double ikat from Tenganan, Bali, with ritual significance.

- Ikat: Yarn-resist textile made by tying and dyeing threads before weaving.

- Jarik: Javanese term for a long unstitched batik cloth (kain panjang) worn as a lower garment.

- Kain/Kain Panjang: Long rectangle of cloth worn as a skirt or wrap; not necessarily tubular.

- Kamben: Balinese term for temple wrap, worn with a sash (selendang).

- Kebaya: Fitted women’s blouse, often sheer, paired with a batik or songket skirt.

- Kemben: Chest wrap worn in some Javanese and Balinese contexts, sometimes under a kebaya.

- Peci (Songkok/Kopiah): Men’s cap widely worn in Indonesia, especially for formal and religious events.

- Sarong/Sarung: Tubular or wrapped lower garment worn by all genders across regions.

- Selendang: Long scarf or sash used for modesty, support, or ceremony.

- Songket: Supplementary-weft textile with metallic threads forming floating motifs.

- Tapis: Lampung textile using embroidery and couching on striped grounds, worn as a tube skirt.

- Ulap Doyo: East Kalimantan Dayak textile woven from doyo leaf fiber.

- Ulos: Batak ceremonial cloth, central to kinship rites and life-cycle events.

- Udeng: Balinese men’s headcloth worn to temples and ceremonies.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the main traditional clothes of Indonesia and their names?

The main traditional clothes include batik, kebaya, sarong, ikat, songket, ulos, tapis, Baju Bodo, and Ulap Doyo. These vary by region and occasion, from daily wear to weddings and rituals. A kebaya is a women’s blouse; a sarong is a tubular wrap. Ulos (Batak) and tapis (Lampung) are ceremonial cloths with specific meanings.

What do men wear in Indonesia traditional clothes?

Men commonly wear a baju koko shirt, sarong, and a peci cap for religious and formal events. In Java, men may wear a beskap jacket with batik cloth and blangkon headgear. For weddings, regional sets (e.g., songket with accessories in Sumatra) are used. Daily traditional wear often centers on the sarong and simple shirts.

What is the difference between batik, ikat, and songket?

Batik is a wax-resist dye technique applied to fabric to create patterns. Ikat is a yarn-resist method where threads are tied and dyed before weaving. Songket is a supplementary-weft weave that inserts metallic threads for shimmering designs. All three are used for ceremonial and formal clothing across regions.

How do you wear an Indonesian sarong correctly?

Step into the tubular cloth, pull it to waist height, and align the seam to one side or back. Fold excess fabric inward to fit your waist, then roll the top edge down 2–4 times to secure. For active movement, add one extra fold and roll. Women may wear it higher and pair with a kebaya.

What do colors and motifs mean in Indonesian textiles?

Colors and motifs signal status, age, marital state, and spiritual protection. For example, Baju Bodo colors encode age and status, and Batak ulos uses a red–black–white triad for life-cycle symbolism. Common motifs include flora, fauna, and geometric cosmology. Courtly batik often uses muted soga browns with refined geometry.

Where can I buy authentic Indonesian traditional clothes?

Buy from artisan cooperatives, certified batik houses, museum shops, and fair-trade marketplaces. Look for hand-drawn batik (batik tulis) or hand-stamped (batik cap), natural fibers, and maker provenance. Avoid mass-printed “batik print” when seeking craft value. Expect higher prices for handwork and metallic-thread songket.

Is Indonesian batik recognized by UNESCO and why does it matter?

Yes, Indonesian batik is inscribed by UNESCO as Intangible Cultural Heritage. This recognition supports preservation, education, and fair valuation of artisans’ work. It encourages responsible buying and helps sustain traditional knowledge. It also raises global awareness of Indonesia’s textile heritage.

Conclusion and next steps

Indonesia traditional clothes unite technique, artistry, and community meaning across a remarkable range of regions. By recognizing the difference between textile processes and garment types, you can read patterns, choose appropriate attire for events, and support artisans responsibly. With careful care and informed buying, these textiles remain vibrant threads in everyday life and ceremony.

Your Nearby Location

Your Favorite

Post content

All posting is Free of charge and registration is Not required.

![Preview image for the video "[Tutorial] Cara Memakai Pakaian Jawa BESKAP SURJAN - How to Wear Javanese Outfits [HD]". Preview image for the video "[Tutorial] Cara Memakai Pakaian Jawa BESKAP SURJAN - How to Wear Javanese Outfits [HD]".](/sites/default/files/styles/media_720x405/public/oembed_thumbnails/2025-08/rPw8XnFWAsacn7FITRh_0fIVwqlt2R9LFJ7p0dcWvjA.jpg.webp?itok=kHJbTvP3)