Indonesia Komodo Dragon: Facts, Islands, and How to Visit Komodo National Park

The Indonesia Komodo dragon is the world’s largest living lizard and a powerful symbol of the Lesser Sunda Islands. You will find practical details on seasons, permits, rangers, and boats from Labuan Bajo, along with essential biology and conservation facts. Use this article to prepare for respectful wildlife viewing and a smooth trip.

Komodo dragon overview (quick definition)

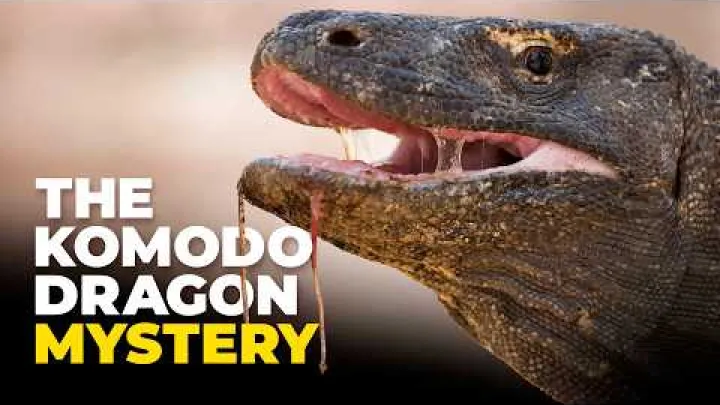

The Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis) is a giant monitor lizard endemic to a small cluster of Indonesian islands. Adults reach impressive lengths, have serrated teeth, and produce venom that affects blood clotting in prey. Their range is naturally restricted, and they function as apex predators in dry island ecosystems of the Lesser Sundas.

These lizards live in savanna–forest mosaics and along coasts, where they ambush deer, pigs, and other prey. They can swim between islands and use their keen sense of smell to locate carrion. Due to their limited distribution and sensitivity to environmental change, they are protected in Komodo National Park and are listed as Endangered globally.

What makes Komodo dragons unique (size, venom, distribution)

Komodo dragons are the largest living lizards, with clear differences between males and females. Adult males average about 2.6 m in length and females around 2.3 m, measured from snout to tail tip. Their heavy bodies, strong limbs, and muscular tails help them overpower prey, while their endurance is limited, favoring ambush over long pursuits. These measurements are provided in metric to keep comparisons consistent.

They produce venom with anticoagulant effects, which means the compounds interfere with blood clotting and can increase blood loss and shock in prey. This modern understanding replaces the outdated “dirty mouth” myth that once suggested oral bacteria were the primary killing mechanism. Their distribution is restricted to Indonesia’s Lesser Sunda Islands, where they act as apex predators and influence prey behavior, scavenger dynamics, and habitat use. This unusual combination of size, venom, and island-limited range makes the species exceptional in the reptile world.

Quick facts and essential metrics

Below are concise details travelers and students often look for before planning a Komodo dragon Indonesia trip. Figures reflect widely cited ranges and may be refined by ongoing research, so use them as approximate guides rather than fixed limits.

- Scientific name: Varanus komodoensis

- Conservation status: Endangered (global)

- Range (wild): Komodo, Rinca, parts of Flores, Gili Motang, Gili Dasami

- Average length: males ~2.6 m; females ~2.3 m

- Top sprint speed: up to ~20 km/h (short bursts)

- Swimming: ~5–8 km/h; capable of crossing short channels

- Venom: anticoagulant compounds that disrupt clotting

- Best viewing: often in the local dry season, conditions vary by year

These quick facts help set realistic expectations for size, speed, and behavior. Always verify any critical details with up-to-date park briefings or ranger notes, since conditions and access rules can change, especially around sensitive wildlife periods or after weather events.

Where Komodo dragons live in Indonesia

They live on Komodo and Rinca, smaller islets such as Gili Motang and Gili Dasami, and scattered sites on the western and northern parts of Flores. These locations make up the core of their remaining wild range.

Most visitors see dragons by joining ranger-led walks on Komodo or Rinca Islands, where dedicated stations and marked trails support safe wildlife viewing. Populations on Flores are more fragmented, and sightings can be less predictable without local expertise. If you plan a Komodo dragon Indonesia tour, check that your itinerary includes islands with current, reliable sightings. Below is a practical overview of each island’s status and access considerations.

Current islands and population notes (Komodo, Rinca, Flores, Gili Motang, Gili Dasami)

Wild Komodo dragons are confirmed on Komodo, Rinca, parts of Flores, Gili Motang, and Gili Dasami. Komodo and Rinca are the main strongholds and the focus of most visitor routes. Flores holds smaller, more fragmented groups that are not as straightforward to see on a short trip. Padar had records decades ago but does not host wild dragons today.

Local population counts can fluctuate as surveys refine estimates and as environmental conditions shift. Rangers and researchers continue to update data and adjust visitor guidance. The table below summarizes current knowledge at a high level to support basic trip planning. Treat it as a snapshot rather than a fixed inventory.

| Island | Status | Protection | Notes on access and sightings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Komodo | Stronghold | Komodo National Park | Ranger stations, marked trails, commonly included on tours from Labuan Bajo. |

| Rinca | Stronghold | Komodo National Park | Frequent sightings, shorter hikes; often a reliable choice for day trips. |

| Flores (selected areas) | Fragmented | Mixed (outside park) | More variable sightings; best with local experts and tailored itineraries. |

| Gili Motang | Small population | Komodo National Park | Access limited; not a standard stop for most visitor boats. |

| Gili Dasami | Small population | Komodo National Park | Remote and sensitive; rarely included in general tours. |

| Padar | Absent | Komodo National Park | Scenic viewpoint; no wild Komodo dragons currently. |

Habitats and climate zones across the islands

Komodo dragons use a patchwork of habitats: open savanna grasslands, monsoon forest pockets, and coastal zones with mangroves and beaches. Seasonal rainfall strongly shapes water availability, which in turn guides deer and pig movements—key prey that influence when and where dragons are active. Forest patches offer shade and cooler ground during the hottest hours, while open areas make ambush hunting easier at dawn and dusk.

Elevation and slope create microhabitats where temperature and moisture differ. Fire regimes, sometimes influenced by human land use, can alter habitat quality and connectivity between foraging grounds and nesting sites. For practical viewing, plan early morning or late afternoon walks and follow ranger advice about shaded routes. These tips improve comfort and viewing probabilities without guaranteeing sightings, since wildlife behavior varies daily and by season across the Lesser Sunda Islands.

How to visit Komodo National Park

Most travelers reach Komodo National Park through Labuan Bajo, a small port town on the western end of Flores. From there, licensed operators run day trips and liveaboard cruises to Komodo, Rinca, and scenic spots like Padar’s viewpoint. Park rules require visitors to join ranger-led walks for land-based wildlife viewing, and boats must comply with local safety and permitting regulations.

Before booking, review seasonal conditions, any advisories, and what your tour includes. Operators may list snorkeling gear, meals, and drinking water, while park entry and ranger fees can be additional. Responsible visitors prioritize licensed guides, safe boats, and respectful wildlife practices that maintain Komodo dragon natural behavior.

Getting there: Labuan Bajo gateway and boat routes

Overland routes across Flores and ferry combinations exist, but most travelers fly to save time. From the harbor, wooden local boats and modern speedboats run to Rinca and Komodo, with itineraries that often combine wildlife walks and snorkeling at nearby bays, subject to sea conditions.

Safety is essential on the water. Choose operators that provide life jackets for all passengers, carry functioning radios or mobile communication, and follow capacity limits. Ask about the captain’s license and the boat’s operator permit, and confirm fuel and weather checks before departure. Routes can change due to wind, swell, or temporary closures, so keep plans flexible and verify schedules the day before you sail.

Permits, guides, and park rules

Komodo National Park requires entry tickets and ranger-led walks for designated land activities. Fees are typically paid at ranger stations or arranged through your tour operator. Common categories include a park entry ticket, ranger/guide fee for the walk, and activity-specific fees such as camera or diving charges where applicable. Cash is useful, as not all sites accept cards or have reliable connectivity.

On trails, keep 5–10 m distance from dragons, follow single-file guidance, and never feed or bait wildlife. Group size limits help reduce disturbance, and drones require a permit. Rangers provide a safety briefing and explain the route; always comply with their instructions. Violations can lead to penalties under Indonesian regulations and can harm both visitors and wildlife.

Tour types: day trips vs. liveaboard

Day trips by speedboat or wooden boat typically visit 1–3 islands, including a ranger-led walk on Komodo or Rinca and time for snorkeling. These trips are efficient for tight schedules but allow limited time at each stop. Liveaboard trips of 2–4 days add multiple wildlife and marine sites at a slower pace, which benefits photographers and divers who prefer sunrise and sunset opportunities.

Typical inclusions are a licensed guide, meals, drinking water, and snorkeling gear. Park fees, fuel surcharges, and specialized activities may be priced separately. Prices and inclusions vary by operator, boat type, and season, so read itineraries carefully. Choose companies with a clear wildlife policy: no feeding, no baiting, and strict adherence to park rules for a responsible Komodo dragon Indonesia tour.

Best time to see Komodo dragons

Seasonality affects trekking comfort, boat operations, and overall visibility. The local dry season typically brings lower vegetation and more stable sea conditions, while the wet season brings greener landscapes and fewer visitors but can disrupt plans with rain, wind, or swell. Because weather patterns vary across the Lesser Sunda Islands and can shift year to year, use broad windows rather than fixed dates when planning.

Wildlife behavior also changes with temperature and breeding periods. Early morning and late afternoon are often the most comfortable times for both visitors and dragons. Rangers know how to adjust routes to avoid sensitive nesting areas and to focus on shade and water sources when heat is high.

Dry season vs. wet season visibility

During hotter, drier months, dragons may linger near shade, water points, or breezy coastal zones, which can bring occasional sightings near ranger stations and forest edges. The trade-off is higher visitor numbers at peak months.

The wet season, often January to March, transforms hills into vivid greens and reduces crowds. However, rain and wind can lead to itinerary changes or cancellations. If you visit in this window, allow buffer days, consider larger boats for stability, and keep expectations flexible. Always confirm conditions locally, as rainfall and wind patterns vary across the archipelago and can differ from one year to the next.

Wildlife behavior, sea conditions, and closures

Dragon behavior reflects breeding cycles. Mating and nesting periods can increase sensitivity around nest mounds, and rangers may reroute walks to maintain safe distances and reduce disturbance. Early and late walks often provide the best balance between activity and heat, reducing stress on both wildlife and visitors.

Sea conditions follow seasonal trade winds and regional swells, which affect crossing times and snorkeling visibility. Operators may cancel or modify routes for safety. Some trails or lookouts may close temporarily for maintenance or habitat protection. Plan using conservative time windows rather than fixed dates, and confirm access the day before your trip.

Safety and visitor guidelines

Responsible viewing keeps both people and wildlife safe. Komodo dragons are powerful predators, but incidents are rare when visitors follow ranger instructions and maintain distance. All official land visits in Komodo National Park are ranger-led, and briefings explain how to position yourself, how to move on trails, and what to do if a dragon changes direction toward the group.

A simple set of rules goes a long way: stay calm, keep hands free, and avoid sudden movements. Pay attention to the path surface and roots, and do not crowd wildlife or block escape routes. Respect legal requirements, local signage, and seasonal restrictions that support conservation and visitor safety.

Distance rules, ranger-led visits, and risk context

Always keep 5–10 m from Komodo dragons and follow single-file guidance on narrow sections. Never corner a dragon or run; instead, calmly follow the ranger’s instructions for spacing and direction changes. Rangers carry deterrent tools and explain emergency procedures before walks begin.

While social media can amplify isolated incidents, the overall risk is low when regulations are respected. Legal compliance and personal responsibility are essential: stay on marked routes, avoid provoking wildlife, and keep your group together. If you have concerns, raise them during the briefing so the ranger can adapt the route or pace.

What to wear, what to bring, and prohibited actions

Wear closed-toe walking shoes with grip, lightweight long sleeves, and a hat. Bring at least one bottle of water per person, sunscreen, and insect repellent. Carry cash for local fees, since card machines are not always available. Keep food sealed and out of sight, and choose shaded areas for breaks while maintaining a safe buffer from wildlife.

Prohibited actions include feeding or baiting animals, leaving marked trails, and flying drones without a permit. Never litter; pack out plastics and follow Leave No Trace principles on beaches and viewpoints. During meal breaks, keep your distance and do not leave food unattended to avoid attracting wildlife.

- Responsible Travel Checklist: book licensed operators and guides.

- Follow ranger instructions at all times.

- Maintain 5–10 m distance from Komodo dragons.

- No feeding, baiting, or provoking wildlife.

- Respect seasonal closures and trail reroutes.

- Carry water, sun protection, and secure your food.

Conservation status and threats

Komodo dragons are listed as Endangered due to their naturally small range and vulnerability to environmental change. While protection inside Komodo National Park provides a strong foundation, subpopulations vary in stability. Some areas show relative consistency, while others experience declines linked to habitat pressures, prey availability, or human activity outside core protections.

Long-term conservation depends on effective law enforcement, continued monitoring, and cooperation with local communities. Visitor behavior also matters. Respecting park rules, avoiding disturbance, and supporting responsible operators helps ensure that tourism provides conservation benefits rather than added stress.

IUCN Endangered status and population trend

The global Endangered status reflects a restricted island distribution and limited capacity to expand into new habitats as conditions change. Overall numbers are modest, with local fluctuations across islands and through time. Within Komodo National Park, legal protection and ranger presence improve outlooks, yet uncertainties remain for remote or fragmented sites on Flores and smaller islets.

Monitoring programs refine trend estimates and guide management responses, such as adjusting visitor access or increasing patrols. To avoid confusion, it is best not to cite precise totals unless they come from current, widely accepted assessments. Instead, focus on the clear priority: maintaining habitat quality, prey resources, and effective protection across the species’ limited range.

Climate risk, habitat loss, and tourism pressures

Climate change can raise temperatures and alter rainfall, compressing suitable habitat and affecting prey abundance. Sea-level rise may influence coastal nesting or resting zones in low-lying areas. Outside protected cores, habitat fragmentation and human encroachment can isolate small groups and reduce genetic exchange.

Tourism is a double-edged factor: poorly managed visits can disturb wildlife, while well-regulated tourism funds protection and community benefits. Visitors can reduce impacts by booking licensed operators, following rangers, keeping distances, and never feeding animals. Community engagement and ranger presence remain central to long-term success.

Biology and key facts

Komodo dragons are powerful, energy-efficient ambush predators built for short bursts of activity. Their heat load and body size limit endurance, but they are capable swimmers that cross short channels between islands. Juveniles spend more time in trees to avoid larger predators, including adult dragons.

Beyond hunting tactics, their reproduction includes rare capabilities such as parthenogenesis, which can produce viable eggs without mating. While this is remarkable, it also highlights genetic considerations for small island populations, where diversity is important for resilience.

Size, speed, and swimming ability

Adult males average roughly 2.6 m in length, and females around 2.3 m, with a maximum verified length in the region of 3.0 m. These measurements reflect wild individuals and can vary by age, season, and body condition. Large body mass favors a powerful ambush style rather than long-distance chases.

Dragons can sprint up to about 20 km/h in short bursts and swim around 5–8 km/h. They often cross small channels when moving between nearby islands or bays. Because endurance is limited, they conserve energy by selecting shaded rest spots during the hottest hours and concentrating activity around dawn and dusk.

Venom and hunting strategy

Komodo dragons use serrated teeth and powerful neck muscles to create deep lacerations in prey. Their venom contains compounds with anticoagulant effects, which means it interferes with the body’s ability to form stable blood clots. In simple terms, the blood keeps flowing more than it normally would, which increases the chance of shock and collapse.

They target deer, pigs, and occasionally water buffalo, and they readily scavenge carcasses located through chemoreception. A forked tongue collects scent particles and transfers them to a sensory organ that helps detect food sources over distance. Feeding can occur in groups, with a fluid hierarchy at the carcass.

Reproduction and parthenogenesis

Komodo dragons have a seasonal breeding cycle. After mating, females lay eggs in nests, sometimes in old mound nests, and guard the site for a limited time. Clutch sizes are moderate, and hatchlings face high predation risk, which is why juveniles spend time in trees where they forage and avoid larger dragons.

Parthenogenesis allows a female to produce viable eggs without a male. While this can help isolated individuals reproduce, it reduces genetic mixing. In simple terms, genetic diversity provides a broader toolkit for populations to cope with change. Small island populations benefit when different lineages mix, which is why habitat connectivity and subpopulation health matter.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Komodo dragons only found in Indonesia?

Yes, wild Komodo dragons are naturally found only in Indonesia’s Lesser Sunda Islands. Today they occur on Komodo, Rinca, Flores, Gili Motang, and Gili Dasami. They are absent from Padar and do not have wild populations outside Indonesia. Captive dragons exist globally in accredited zoos.

How big do Komodo dragons get in the wild?

Adult males average about 2.6 m in length and 79–91 kg; females average about 2.3 m and 68–73 kg. Maximum verified wild length is roughly 3.04 m. Body mass varies with season and feeding; very large stomach contents can temporarily raise weights.

How fast can Komodo dragons run and swim?

Komodo dragons can sprint up to about 20 km/h for short bursts. They are strong swimmers at roughly 5–8 km/h and can cross short channels between islands. Long-distance running is not sustained due to their large body mass and heat load.

Do Komodo dragons have venom?

Yes, Komodo dragons produce venom with anticoagulant effects that promote rapid blood loss and shock in prey. Serrated teeth cause deep lacerations, and the venom compounds disrupt clotting. The “dirty mouth” infection myth is outdated; their oral microbiome is not the primary killing mechanism.

Can you see Komodo dragons on Padar Island today?

No, Komodo dragons are currently absent from Padar Island, where they were last observed in the 1970s. Padar remains a popular viewpoint stop, but sightings occur on Komodo, Rinca, parts of Flores, Gili Motang, and Gili Dasami. Confirm your tour itinerary for wildlife stops.

Which is better for sightings, Komodo Island or Rinca Island?

Both islands offer reliable sightings, with ranger stations and marked trails. Rinca often provides shorter hikes and frequent encounters; Komodo has broader habitats and longer routes. Your choice can be guided by season, sea conditions, and tour logistics from Labuan Bajo.

Is feeding or baiting Komodo dragons legal in Indonesia?

No, feeding, baiting, or provoking Komodo dragons is illegal and unsafe. It can alter natural behavior, increase conflict risk, and lead to penalties. Always follow ranger instructions and maintain safe viewing distances.

Is it safe to visit Komodo Island?

Yes, when you follow ranger guidance and park rules. Maintain 5–10 m distance, never run, and stay with your group. Incidents are rare on ranger-led walks, and operators will modify routes or schedules if conditions change.

When is the best time to see Komodo dragons?

The dry season is often preferred for easier hiking and calmer seas, while the wet season brings lush scenery and fewer visitors. Early morning or late afternoon walks improve comfort and sighting chances. Local weather varies, so confirm conditions near your travel dates.

Can children join Komodo dragon walks?

Children can join official ranger-led walks if they can follow instructions and stay close to guardians. Discuss group pace and any concerns with rangers before starting. Operators may have age policies for certain routes or boats.

Conclusion and next steps

Komodo dragons live on a short list of Indonesian islands, with Komodo and Rinca as reliable places for ranger-led sightings. Plan through Labuan Bajo, confirm fees and permits, and follow distance rules for safe viewing. Understanding size, venom, behavior, and conservation needs helps set expectations and supports respectful travel. Check seasonal conditions close to your dates and allow flexibility for weather or temporary closures.

Your Nearby Location

Your Favorite

Post content

All posting is Free of charge and registration is Not required.