Indonesia Gamelan: Instruments, Music, History, and Culture

Heard in Java, Bali, and Sunda, it supports rituals, theater, and dance, and it thrives on stage as concert music. Its sound world uses unique tunings, rich textures, and layered cycles rather than Western harmony. This guide explains instruments, history, tuning systems, regional styles, and how to listen with respect today.

What is gamelan in Indonesia?

Quick definition and purpose

Rather than spotlighting solo virtuosity, the focus is the coordinated sound of the group. The music accompanies dance, theater, and ceremonies, and it is also performed in dedicated concerts and community gatherings.

While instrumental sound defines much of the texture, voice is integral. In Central and East Java, a male chorus (gerongan) and a soloist (sindhen) weave text with instruments; in Bali, choral textures or vocal syllables may punctuate instrumental works; in Sunda, the timbre of the suling (bamboo flute) often pairs with vocals. Across regions, vocal lines sit within the instrumental fabric, adding poetry, narrative, and melodic nuance.

Key facts: UNESCO recognition, regions, ensemble roles

Gamelan is widely practiced across Indonesia and was inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2021. Related ensembles appear in Lombok, while other Indonesian regions maintain distinct musical cultures rather than gamelan per se.

- UNESCO recognition: 2021 inscription highlighting safeguarding and transmission.

- Primary regions: Java (Central and East), Bali, and Sunda; related practices in Lombok.

- Balungan: the core melody carried mainly by metallophones in several registers.

- Colotomic layer: gongs punctuate repeating cycles and mark structural points.

- Kendang (drums): lead tempo, cue transitions, and shape expressive flow.

- Elaboration and vocals: instruments and singers ornament and comment on the core line.

Together, these roles create a layered texture where each part has responsibility. Listeners hear a musical “ecosystem” in which timing, melody, and ornament interlock, giving gamelan its characteristic depth and resonance.

Origins and historical development

Early evidence and origin myths

Temple reliefs from Central Java, often dated around the 8th–10th centuries, depict musicians and instruments that foreshadow later metallophones and gongs. Inscriptions and court chronicles from the pre-Islamic period also reference organized music-making in royal and ritual settings.

Mythic accounts, often told in Java, attribute gamelan’s creation to a deity such as Sang Hyang Guru, underscoring its sacred associations. These narratives do not describe historical invention in a literal way; rather, they communicate the music’s cosmological significance and its perceived role in harmonizing social and spiritual life. Distinguishing legend from archaeology helps us appreciate both the reverence for gamelan and the gradual formation of its instruments and repertoire.

Courts, religious influences, and colonial contact

Royal courts, especially in Yogyakarta and Surakarta, systematized instrument sets, etiquette, and repertoire, providing a framework for teaching and performance that still shapes Central Javanese practice. Bali’s courts developed parallel, distinctive traditions with their own ensembles and aesthetics. These courtly institutions did not produce a single, uniform style; rather, they nurtured multiple lineages that coexisted and evolved.

Hindu-Buddhist legacies influenced literary texts, iconography, and rituals, while Islamic aesthetics shaped poetry, ethics, and performance contexts in many Javanese centers. During the colonial era, intercultural contact spurred documentation, early notation practices, and touring performances that amplified international awareness. These influences overlapped rather than replaced one another, contributing to the diverse forms of gamelan encountered across the archipelago.

Instruments in a gamelan ensemble

Core melody instruments (balungan family)

Balungan refers to the core melodic line that anchors the ensemble’s pitch framework. It is typically realized by metallophones in different registers, creating a sturdy skeleton around which other parts elaborate. Understanding the balungan helps listeners follow form and hear how layers relate.

The saron family includes demung (low), barung (middle), and panerus or peking (high), each struck with a mallet (tabuh) to articulate the melody. The slenthem, with suspended bronze keys, supports the lower register. Together they render the balungan in both slendro and pelog tunings, with the lower instruments providing weight and the higher saron clarifying contour and rhythmic drive.

Gongs and drums (colotomic and rhythmic layers)

Gongs articulate colotomic structure, a cyclical framework where specific instruments mark recurring points in time. The largest gong, the gong ageng, signals major cycle endings, while kempul, kenong, and kethuk define intermediate divisions. This patterning or “punctuation” lets players and listeners orient themselves within long musical arcs.

The kendang (drums) guide tempo, shape expressive timing, and cue sectional transitions and irama shifts. Named forms such as lancaran and ladrang differ by cycle length and gong placement, offering contrasting feels for dance, theater, or concert pieces. The interplay between drum leadership and colotomic punctuation sustains momentum and clarity across extended performances.

Elaborating instruments and vocals

Elaborating parts ornament the balungan, enriching the texture with rhythmic and melodic detail. Bonang (sets of small gongs), gendèr (metallophones with resonators), gambang (xylophone), rebab (bowed spike fiddle), and siter (zither) each contribute characteristic patterns. Their lines vary density and register, creating a constellation of motion around the core melody.

Vocals consist of a gerongan (male chorus) and a sindhen (soloist), who adds poetic text and flexible melodic nuance above the instrumental weave. The resulting texture is heterophonic: multiple parts render related versions of the same melodic idea, not in strict unison or harmony, but in interwoven strands. This approach invites attentive listening to how voices and instruments converse within shared melodic space.

Craftsmanship, materials, and tuning practices

Gamelan instruments are crafted by specialist makers who cast and hand-tune bronze alloys into gongs and keys. Regional lineages in Java and Bali maintain distinctive approaches to casting, hammering, finishing, and tuning. The process balances metallurgy, acoustics, and aesthetic judgment to achieve a coherent ensemble sonority.

Each gamelan is tuned internally; there is no universal pitch standard across sets. Slendro and pelog intervals are shaped by ear to suit local taste and repertoire, yielding subtle differences from set to set. Some community ensembles use iron or brass alternatives for affordability and durability, while bronze remains prized for its warmth and sustain.

Tuning, modes, and rhythmic structure

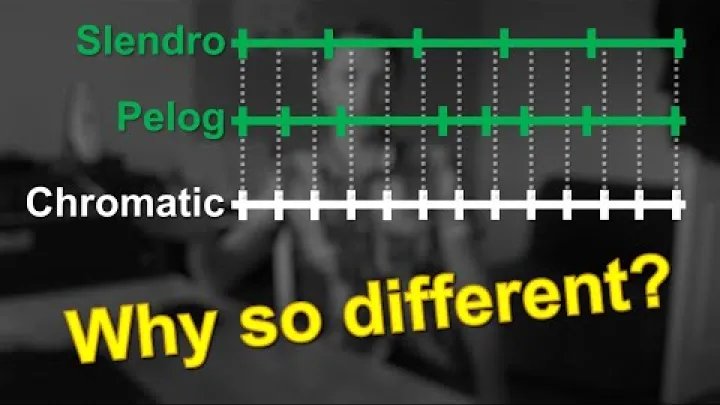

Slendro vs pelog tunings (separate instrument sets)

Gamelan uses two primary tuning systems. Slendro is a five-tone scale with relatively even spacing, while pelog is a seven-tone scale with unequal intervals. Because pitches are not standardized, ensembles maintain separate instrument sets for each tuning rather than retuning a single set.

It is important not to assume Western equal temperament. Slendro and pelog intervals vary between ensembles, producing distinct local color. In practice, pieces select a subset of tones, especially in pelog where not all seven notes are used at once, and they emphasize particular pitches to establish mood and melodic pathways.

Pathet (mode) and irama (tempo and density)

Pathet functions as a modal system that guides focal tones, cadences, and characteristic movements within slendro or pelog. In Central Java, for example, slendro pathet often include nem and manyura, each shaping where phrases feel at rest and which tones receive emphasis. Pelog pathet likewise define preferred notes and cadential formulas, influencing its expressive profile.

Irama describes the relationship between overall tempo and the density of subdivisions among different parts. When the ensemble shifts irama, elaborating instruments may play proportionally more notes while the core melody slows its surface rhythm, creating a spacious yet detailed texture. The kendang and leading instruments signal these changes, coordinating transitions that listeners perceive as expansions or contractions of musical time.

Colotomic cycles and the role of the gong ageng

Colotomic cycles organize time through recurring patterns of gong strokes. The gong ageng anchors the largest structural boundary, closing major cycles and providing a sonic center. Other gongs articulate intermediate markers so that long forms remain intelligible and grounded.

Common Central Javanese forms include ketawang (often 16 beats), ladrang (often 32 beats), and lancaran (often 16 beats with a distinct accent pattern). Within a cycle, the kenong divides the structure into large sections, the kempul adds secondary punctuations, and the kethuk marks smaller subdivisions. This hierarchy enables rich elaboration while preserving clear orientation for performers and audience.

Gamelan music of Indonesia: regional styles

Central and East Java aesthetics: alus, gagah, and arèk

Java hosts multiple aesthetics that balance refinement and vigor. Central Java often values alus qualities—subtle pacing, soft dynamics, and expressive restraint—alongside gagah pieces that project energy and strength. Ensembles cultivate both characters to support dance, theater, and concert needs across different occasions.

East Java is sometimes associated with arèk style, which can feature brighter timbres and brisker tempi. Yet within both provinces, diversity is the norm: court traditions, city ensembles, and village groups maintain varied repertoires and performance practices. Terminology can be local, and musicians adapt nuance to the venue, ceremony, or theatrical context.

Bali: interlocking techniques and dynamic contrasts

Balinese gamelan is renowned for interlocking techniques known as kotekan, in which two or more parts dovetail to create rapid composite rhythms. Ensembles such as gamelan gong kebyar showcase dramatic dynamic shifts, sparkling articulation, and tight coordination that demand high ensemble precision.

Bali hosts many ensemble types beyond kebyar, including gong gede, angklung, and semar pegulingan. A hallmark of Balinese tuning is paired instruments set slightly apart to produce ombak, a beating “wave” that gives the sound its vibrancy. These features combine to create textures that feel both intricate and propulsive.

Sunda (degung) and other local variants across Indonesia

In West Java, Sundanese degung presents a distinct ensemble, modal practice, and repertoire. The suling bamboo flute often carries lyrical lines over metallophones and gongs, lending a transparent timbre profile. While related in concept to Javanese and Balinese traditions, degung differs in tuning, instrument make-up, and melodic treatment.

Elsewhere, Lombok maintains related gong traditions, and many Indonesian regions have different heritage ensembles rather than gamelan itself. Examples include talempong in West Sumatra or tifa-centered traditions in Maluku and Papua. This mosaic reflects Indonesia’s cultural breadth without implying any hierarchy among local arts.

Indonesia gamelan music: cultural roles and performance contexts

Wayang kulit (shadow theater) and classical dance

Gamelan plays a central role in wayang kulit, the Javanese shadow-puppet theater. The dalang (puppeteer) directs pacing, cues, and character entrances, and the ensemble responds to spoken lines and dramatic arcs. Musical signals align with plot events, shaping mood and guiding the audience through episodes.

Classical dance also relies on specialized pieces and tempos. In Java, works such as bedhaya emphasize refined motion and sustained sonorities, while in Bali, legong highlights quick footwork and sparkling textures. It is useful to distinguish wayang kulit from other puppet forms such as wayang golek (rod puppets), as each uses tailored repertoire and cueing systems within the broader gamelan tradition.

Ceremonies, processions, and community events

In many villages, seasonal rituals call for specific pieces and instrument combinations, reflecting local custom and history. Musical choices are closely linked to the event’s purpose, time of day, and venue.

Processional genres such as Balinese baleganjur energize movement through streets and temple grounds, with drums and gongs coordinating steps and spatial transitions. Etiquette, repertoire, and dress vary by locality and occasion, so visitors should observe local guidance. Typical contexts include palace events, temple festivals, community celebrations, and arts center programs.

Learning and preservation

Oral pedagogy, notation, and ensemble practice

Gamelan is primarily taught through oral methods: imitation, listening, and repetition in a group. Students learn by cycling through instruments, internalizing timing, and feeling how parts interlock. This approach trains ensemble awareness as much as individual technique.

Cipher notation (kepatihan) supports memory and analysis but does not replace aural learning. Foundational competence often develops over months with regular rehearsals, and deeper repertoire study can extend over years. Progress depends on steady ensemble practice, where players learn cues, irama changes, and sectional transitions together.

UNESCO 2021 listing and transmission initiatives

UNESCO’s 2021 inscription of gamelan on the Representative List affirms its cultural significance and encourages safeguarding. The recognition strengthens ongoing efforts to document, teach, and sustain the tradition across Indonesia’s provinces and abroad.

Transmission relies on many actors: government cultural offices, kraton (palaces), sanggar (private studios), schools, universities, and community groups. Youth ensembles, intergenerational workshops, and public performances keep knowledge circulating, while archives and media projects broaden access without displacing local teaching lineages.

Global influence and modern practice

Western classical and experimental engagement

Gamelan has long inspired composers and sound artists intrigued by its sonorities, cycles, and tunings. Historical figures like Debussy encountered gamelan and explored new coloristic ideas; later, composers such as John Cage and Steve Reich engaged aspects of structure, texture, or process in their own ways.

The exchange is reciprocal. Indonesian composers and ensembles collaborate internationally, commission new works for gamelan, and adapt techniques across genres. Contemporary pieces may integrate electronics, theater, or dance, expanding the repertoire while keeping Indonesian agency at the center of innovation.

Universities, festivals, and recordings worldwide

Universities and conservatories across Asia, Europe, and the Americas maintain gamelan ensembles for study and performance. These groups often host workshops with visiting Indonesian artists, supporting both technique and cultural context. Seasonal concerts introduce new audiences to instruments, forms, and repertoire.

In Indonesia, festivals and palace or temple programs present court traditions, community groups, and contemporary compositions. Record labels, archives, and digital platforms offer extensive listening resources, from classic court recordings to modern collaborations. Schedules and offerings change periodically, so it is best to verify current information before planning a visit.

How to listen to gamelan today

Concerts, community ensembles, and digital archives

In Java, keraton (palaces) in Yogyakarta and Surakarta host performances and rehearsals; in Bali, temple ceremonies, arts centers, and festivals feature varied ensembles. Community groups often welcome observers, and some arrange introductory sessions for visitors or students.

Museums, cultural centers, and online archives curate recordings, films, and explanatory materials. Check local calendars and holidays, because public events cluster around specific seasons. Access may differ between public performances and private ceremonies, where invitations or permissions are required.

Respectful listening, etiquette, and audience tips

Audience etiquette supports both musicians and hosts. Many venues consider instruments, especially gongs, to be sacred objects, so visitors should avoid touching them unless explicitly invited.

General best practices vary by location, but the following tips are widely applicable:

- Observe quietly during key structural moments, especially when the gong ageng sounds.

- Do not step over instruments or sit on instrument frames; ask before approaching the set.

- Follow seating, footwear, and photography rules as posted or announced on site.

- Arrive early to settle in, and stay through complete cycles to experience the musical form.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is gamelan in Indonesia and how is it defined?

Gamelan is Indonesia’s traditional ensemble music centered on bronze percussion, especially gongs and metallophones, with drums, strings, winds, and voice. It functions as a coordinated group, not as solo showpieces. Major centers include Java, Bali, and Sunda, with distinct styles.

What are the main instruments in a gamelan ensemble?

Core families are metallophones (saron, slenthem), knobbed gongs (gong ageng, kenong, kethuk), drums (kendang), elaborating instruments (bonang, gendèr, gambang, rebab, siter), and vocals. Each family has a defined role in the ensemble’s layered texture.

How do slendro and pelog tunings differ in Indonesian gamelan?

Slendro has five tones per octave with relatively even spacing; pelog has seven tones with uneven intervals. Each tuning requires a separate instrument set. Ensembles select modes (pathet) within each tuning to shape mood and melodic focus.

What is the difference between Javanese and Balinese gamelan styles?

Javanese gamelan is generally smoother and meditative, emphasizing pathet, irama, and subtle ornamentation. Balinese gamelan is brighter and dynamic, with fast interlocking parts and sharp contrasts in tempo and volume.

What does the gong ageng do in gamelan music?

The gong ageng marks the end of major musical cycles and anchors the ensemble’s timing and sonority. Its deep resonance signals structural points and provides a tonal center for performers and listeners.

Is gamelan found across all regions of Indonesia?

Gamelan is concentrated in Java, Bali, and Sunda; related ensembles exist in Lombok. Many other regions have distinct traditions (for example, talempong in West Sumatra or tifa in Maluku-Papua) rather than gamelan.

How is gamelan taught and learned?

Gamelan is taught primarily through oral methods: demonstration, repetition, and ensemble practice. Notation may assist learning, but memorization and listening lead, often over months to years depending on repertoire.

Where can I hear gamelan performances in Indonesia today?

You can hear gamelan in cultural centers and palaces in Yogyakarta and Surakarta, at temple ceremonies and festivals in Bali, and in university or community ensembles. Museums and archives also provide recordings and scheduled demonstrations.

Conclusion and next steps

Gamelan brings together distinctive instruments, tunings, and performance practices to serve theater, dance, ritual, and concert life across Indonesia. Its layered structures, local variations, and living pedagogy make it a dynamic tradition with global resonance. Listening closely to cycles, timbres, and modal color reveals the artistry that sustains gamelan today.

Your Nearby Location

Your Favorite

Post content

All posting is Free of charge and registration is Not required.

![Preview image for the video "(Tutorial) Belajar SARON DEMUNG / Lancaran KEBO GIRO / Learning Javanese Gamelan Music Jawa [HD]". Preview image for the video "(Tutorial) Belajar SARON DEMUNG / Lancaran KEBO GIRO / Learning Javanese Gamelan Music Jawa [HD]".](/sites/default/files/styles/media_720x405/public/oembed_thumbnails/2025-09/_APFYfObdG84YMXXUJKl6VXKqQO2bff1Cj6PY_lrgYc.jpg.webp?itok=s0TNckRH)

![Preview image for the video "[SABILULUNGAN] SUNDANESE INSTRUMENTALIA | DEGUNG SUNDA | INDONESIAN TRADITIONAL MUSIC". Preview image for the video "[SABILULUNGAN] SUNDANESE INSTRUMENTALIA | DEGUNG SUNDA | INDONESIAN TRADITIONAL MUSIC".](/sites/default/files/styles/media_720x405/public/oembed_thumbnails/2025-09/bvr4sFcZ4xRqaLJZvINpASOi0frMz0ccEQtmLd1jdXo.jpg.webp?itok=YuJcwh1k)