Thailand fertility rate: current TFR, trends and outlook 2024–2025

Thailand’s fertility rate has fallen well below the replacement threshold and remains a key driver of demographic change in the country. This guide explains the current total fertility rate, how it is measured, and why it matters for population, the economy, and public services. It also explores trends since the 1960s, regional differences, and lessons from neighboring economies. Readers will find quick facts, definitions, and a concise outlook for 2024–2025.

Quick answer: Thailand’s current fertility rate (2024–2025)

Thailand’s total fertility rate in recent years has hovered around 1.2–1.3 children per woman, far below the approximate replacement level of 2.1. The figure is a period measure, meaning it summarizes fertility under current-year conditions rather than lifetime births of a specific generation. Because TFR is age-standardized, it allows comparisons across time and across countries, even when their age structures differ. As of the latest updates, births remain at historic lows and deaths continue to outnumber births, reflecting a rapidly aging population.

What TFR means and how it is calculated

Total fertility rate (TFR) is the sum of age-specific fertility rates across a woman’s reproductive ages. In practical terms, statisticians compute birth rates for 5‑year age bands (for example, 15–19, 20–24, …, 45–49) and add them up. A simple numeric illustration: if the per-woman birth rates for the age groups are 0.05, 0.25, 0.30, 0.25, 0.15, and 0.05, the TFR is 0.05 + 0.25 + 0.30 + 0.25 + 0.15 + 0.05 = 1.05 children per woman. This is a “period” snapshot that answers, “What would the average number of births be if today’s age-specific rates held over a woman’s life?”

TFR differs from “cohort fertility,” which summarizes the actual lifetime births of a specific generation of women born in the same year. Period TFR can go down when births shift to later ages (tempo effects) even if lifetime births change little. Because TFR standardizes for age structure, it is better suited for comparing fertility levels across regions and years than the crude birth rate, which is influenced by how young or old a population is.

Key numbers at a glance (latest TFR, births, deaths, replacement level)

Thailand’s recent TFR is about 1.2–1.3 (latest range for 2024–2025), well below the replacement level of roughly 2.1. In 2022, civil registration recorded about 485,085 births and 550,042 deaths, implying negative natural growth. By 2024, the share of people aged 65 and over was about 20.7%, a clear marker of an aged society. Without a sustained rise in fertility or net immigration, the population will continue to age and gradually decline.

The table below summarizes stable facts that are commonly referenced and are less likely to shift with routine revisions. Figures are rounded and may be updated as official releases arrive.

| Indicator | Thailand (latest indicative) | Reference year |

|---|---|---|

| Total fertility rate | 1.2–1.3 children per woman | 2024–2025 |

| Replacement fertility | ≈2.1 children per woman | Concept |

| Births | ≈485,085 | 2022 |

| Deaths | ≈550,042 | 2022 |

| Population aged 65+ | ≈20.7% | 2024 |

Last reviewed: November 2025.

Trend at a glance: from the 1960s to today

Thailand’s fertility transition has unfolded over six decades, reshaping family size, population growth, and age structure. The country moved from high fertility in the 1960s to well below replacement by the early 1990s. Since then, no durable rebound has occurred, despite cycles of discussion about incentives and family policy. Understanding this trajectory helps interpret today’s very low TFR and the outlook for the 2020s and 2030s.

Long-run decline and below-replacement since the 1990s

Thailand’s TFR fell steeply from the 1960s through the 1980s, driven by voluntary family planning programs, rising education (especially for girls and young women), urbanization, and improved child survival. The replacement threshold of about 2.1 was crossed by the early 1990s, marking a structural shift toward smaller families and later childbearing. In the 2000s and 2010s, the TFR generally fluctuated in the 1.2–1.9 range, with most recent years closer to 1.2–1.5.

Concise milestones often cited for orientation include the following:

- 1960s: around 5–6 children per woman

- 1980s: falling toward 3

- Early 1990s: near 2.1 (replacement) and then below

- 2000s: roughly 1.6–1.9

- 2010s: roughly 1.4–1.6

- 2020s: roughly 1.2–1.3

Despite periodic policy initiatives, a sustained rebound has not materialized. This is consistent with experiences in many advanced Asian economies where deeper structural factors—housing, work intensity, childcare coverage, and gendered caregiving norms—shape fertility behavior.

Negative natural growth (births vs deaths)

Deaths have exceeded births in Thailand since the early 2020s, producing negative natural increase. For example, in 2022 births were about 485,000 while deaths were about 550,000. This gap reflects very low fertility alongside mortality levels that remained elevated during and after the pandemic. As long as TFR stays near 1.2–1.3 and net immigration is limited, the total population is set to decline.

Age structure amplifies the imbalance. Thailand now has a larger cohort at older ages, so the number of deaths each year is higher than in a youthful population, even when age-specific mortality rates improve. At the same time, smaller cohorts of women in their prime childbearing years and delayed family formation both suppress births. This combination reinforces negative natural growth.

Why fertility is low in Thailand

Low fertility in Thailand is the result of many interacting forces rather than a single cause. Economic constraints, changing preferences, and institutional arrangements around work and care all play roles. The sections below group the most cited drivers into costs and timing, workplace and childcare settings, and medical factors.

Costs, careers, and delayed family formation

Rising living costs make it harder to start families early. Urban housing requires larger deposits and higher rents, especially in Bangkok and surrounding provinces. Education expenses—from preschool fees to university tuition and private tutoring—add to the perceived lifetime cost of raising children. Childcare and after-school programs can also be costly or hard to secure in convenient locations.

At the same time, more years spent in education and higher labor force participation raise the opportunity cost of early childbearing. Later ages at first partnership and first birth compress the remaining childbearing years, which mechanically reduces completed family size. Cultural preferences are also shifting: many couples aim for one or two children at most, and some postpone indefinitely. These choices are rational responses to wages, housing, and career ladders, as well as to expectations about the time and energy required to combine work and caregiving.

Workplace policies, childcare, and support gaps

Childcare availability and quality are uneven across regions and across neighborhoods within large cities. Waiting lists and commute times can be major barriers, even when fees are subsidized. Parental leave rules also vary by sector and employment type. In Thailand, maternity leave in the formal sector is typically about 98 days, with payment arrangements split between employers and social insurance where applicable. Paternity leave is more limited, especially outside the public sector, and many informal or self-employed workers have no statutory coverage.

Work intensity matters as well. Long or inflexible hours, late shifts, and weekend work reduce the time parents can devote to caregiving. Practical steps that employers can apply include flexible start–end times, predictable scheduling, remote or hybrid options for suitable roles, and caregiving-friendly performance evaluations. Complementary measures—on-site or partnered childcare, family-friendly housing near workplaces, and benefits that extend to contract and gig workers—can materially reduce the burden of raising children while working.

Limited role of medical infertility

Medical infertility contributes to low fertility outcomes, but it explains only a minority of the decline. A cautious reading suggests roughly one-tenth of the overall shortfall might be linked to biological factors, while the bulk reflects socioeconomic drivers such as delayed marriage, high costs, and constrained time for care. Importantly, infertility prevalence is not the same as national fertility levels: a country can have stable infertility rates yet experience falling TFR due to later and fewer partnerships.

Assisted reproductive technologies (ART) can help some families achieve intended births, but they cannot fully offset demographic headwinds like later childbearing, lower marriage rates, and the high opportunity costs discussed above. Age-related declines in fecundity also become more salient as first births move into the thirties, compounding tempo effects on the period TFR.

Regional and demographic patterns

Fertility in Thailand varies across space and demographic groups. Metropolitan areas exhibit some of the lowest levels due to housing constraints, high costs, and intense work schedules. Rural districts tend to have higher fertility than urban cores but have also experienced long-run declines. Internal migration from rural provinces to Bangkok and other cities shifts births across regions and changes local age structures, which in turn affects local service demand.

Urban vs rural differences

Bangkok and major urban centers tend to show very low TFR by national standards. Housing constraints, commuting time, and the structure of jobs all play a role. Within cities, intra-urban differences matter: central districts usually have fewer families with young children than suburban zones, where larger housing and more schools are available. However, even suburban fertility has trended down over time.

Rural areas typically retain slightly higher fertility but continue to decline as education expands and young adults move for work. Official estimates sometimes smooth seasonal or migratory effects, so short-run changes in registration data may not capture the full dynamics of where births occur versus where parents reside. Over time, these shifts can depopulate some rural communities and concentrate young families in peri-urban belts.

Provincial variation (Yala exception)

Some southern provinces, notably Yala, report TFR near or above replacement compared with the national average. Indicative figures for Yala are often in the range of about 2.2–2.3 children per woman, depending on the reference year and the source. Cultural and religious practices, larger household structures, and local economic patterns contribute to higher parity in these areas relative to Bangkok or the central region.

Data sources and methods matter for provincial comparisons. Many provincial TFR figures are derived from civil registration, while some surveys provide alternative estimates. Late registrations, sampling variation, and differing reference periods can shift rankings from year to year. When comparing provinces, it is best to check whether the numbers are registration-based or survey-based and to note the year coverage.

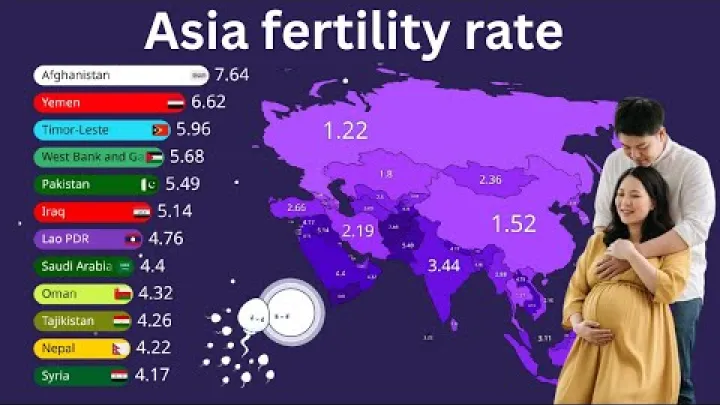

International comparisons

Placing Thailand alongside regional peers helps contextualize how low 1.2–1.3 is and which policy mixes might be relevant. Thailand’s TFR is similar to Japan’s, higher than Korea’s, and lower than Malaysia’s. Singapore also sits at very low levels. While every country’s institutions and norms differ, lessons on childcare, housing, work flexibility, and gender equality have broad relevance for sustaining family formation.

Thailand vs Japan, Korea, Singapore, Malaysia

The table below provides indicative ranges for recent TFR in selected economies. Figures are rounded and depend on the latest available publications; they may be revised as each country updates its statistics. Ranges are used instead of single-year points to reflect normal data revisions.

| Economy | Indicative TFR (latest range) | Approx. reference |

|---|---|---|

| Thailand | 1.2–1.3 | 2024–2025 |

| Japan | ≈1.2–1.3 | 2023–2024 |

| Republic of Korea | ≈0.7 | 2023–2024 |

| Singapore | ≈1.0 | 2023–2024 |

| Malaysia | ≈1.6–1.8 | 2021–2023 |

Policy mixes vary widely. Compared with peers, Thailand’s formal childcare coverage, paid leave scope for fathers, and housing support targeted at young families are evolving areas. Malaysia’s higher TFR reflects a different demographic structure and policy context, while Korea’s extremely low TFR highlights the limits of cash incentives in the absence of broad work–care reforms.

Lessons from East Asia

Evidence from Japan, Korea, and Singapore suggests that cash bonuses alone have modest and short-lived effects on births. More durable results come from integrated approaches: reliable childcare from infancy to school age, longer and better-compensated parental leave for both parents, flexible work arrangements, and housing policies that reduce costs for first-time families.

Consistency over multiple years matters. Families respond to credible, predictable systems rather than one-off programs. Progress on gender equality—in the workplace and in caregiving—correlates with higher fertility intentions and better alignment between desired and achieved family size. Social norms, however, change slowly; sustained engagement is needed to close the gap between intentions and outcomes.

Projections and impacts

Projections point to continued population aging and a shrinking working-age share unless fertility rises or immigration expands. These shifts will affect public finances, labor markets, and community life. The following sections summarize demographic milestones and the economic implications that policymakers, employers, and households will navigate in the 2020s and 2030s.

Aging milestones and support ratio

On current trajectories, the country is expected to become super‑aged around the early 2030s, with roughly 28% aged 65+. These milestones reshape demand for health care, long-term care, and community services, while changing the balance between contributors and beneficiaries in social programs.

The old-age support ratio is commonly defined as the number of working-age people (for example, ages 20–64) per person aged 65 and over. As fertility remains low and cohorts age, the support ratio declines, signaling higher fiscal and caregiving burdens on each worker. Anchoring timelines can help planning: aged society (≈14% 65+) reached earlier in the 2020s, around 20.7% 65+ by 2024, and super‑aged (≈21% 65+) on course for the early 2030s, approaching the high‑20s percent by that time.

Economic, fiscal, and labor market effects

Very low fertility reduces the inflow of young workers, slowing labor force growth and potential output unless productivity rises. Aging increases spending pressures for pensions, health, and long-term care.

Responses include upgrading skills through vocational and higher education, expanding mid‑career reskilling, and encouraging later but flexible retirement options. Technology and automation can lift productivity in logistics, manufacturing, and service scheduling. Well-managed migration can fill hard-to-staff roles while supporting growth. Together, these measures can sustain living standards even as population growth slows or turns negative.

Methodology and definitions

Understanding how fertility is measured makes comparisons clearer and guides responsible use of numbers in public debate. The concepts below clarify the difference between the total fertility rate and the crude birth rate, what replacement fertility means, and how data are assembled and revised.

Total fertility rate vs crude birth rate

TFR measures the average number of children a woman would have if she experienced current age-specific birth rates throughout her reproductive years. It is age-standardized and therefore suitable for comparing fertility levels across places and over time. By contrast, the crude birth rate (CBR) is the number of live births per 1,000 population in a year, which is heavily influenced by age structure.

A simple contrast helps. Suppose a country records 500,000 births with a population of 70 million: its CBR is about 7.1 per 1,000. If its age-specific fertility rates across six 5‑year bands sum to 1.25, then the TFR is 1.25 children per woman. A youthful population can have a high CBR even if TFR is moderate, while an older population can have a low CBR even with the same TFR, because there are fewer women in childbearing ages.

Replacement fertility and why 2.1 matters

Replacement fertility is the level of TFR that would, over the long run and without migration, keep population size stable. In low-mortality settings this is about 2.1 children per woman, allowing for child mortality and the sex ratio at birth. The exact value varies slightly with mortality conditions and sex ratios, so it is best treated as an approximate benchmark rather than a precise target.

Thailand has been below replacement since the early 1990s. Over time, being below replacement reduces population momentum, raises the share of older adults, and increases the old-age dependency burden unless offset by higher fertility or immigration. The longer very low fertility persists, the more difficult it becomes to reverse demographic aging quickly.

Data sources and measurement notes

Key sources include Thailand’s civil registration and vital statistics, national statistical releases, and international databases that harmonize series for comparability. Provisional figures are revised as late registrations arrive and as administrative updates are processed; short-run changes should be interpreted with care, especially for recent months or quarters.

Typical lags between a reference year and finalized data can range from several months to more than a year. Registration-based provincial figures may differ from survey-based estimates due to coverage, timing, and sampling variation. Period TFR can also be affected by the timing of births (tempo effects), so tempo-adjusted indicators can provide complementary insight when available.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the replacement fertility rate and how does Thailand compare today?

The replacement fertility rate is about 2.1 children per woman. Thailand’s TFR is around 1.2–1.3 in recent years, well below replacement. This gap has persisted since the early 1990s and underpins population aging and decline.

How many births and deaths did Thailand record recently (2022–2024)?

In 2022, Thailand recorded about 485,085 births and 550,042 deaths, implying negative natural growth. Subsequent years have remained very low on births, with deaths exceeding births. This pattern signals a continuing population decline absent net immigration.

When will Thailand become a super‑aged society and what does that mean?

Thailand became a fully aged society in 2024 with about 20.7% aged 65+. It is expected to reach super‑aged status around 2033, with roughly 28% aged 65+. Super‑aged means at least 21% of the population is 65 or older.

Can financial incentives alone raise Thailand’s fertility to replacement level?

No. Evidence from Japan, Korea, and Singapore shows cash benefits alone do not restore replacement fertility. Integrated reforms across childcare, housing, work flexibility, gender equality, and social norms are needed for sustained impact.

How much does medical infertility contribute to Thailand’s low birth rate?

Medical infertility explains only a small share, around 10%, of the overall decline. Socioeconomic factors—costs, careers, delayed marriage, and limited childcare—are the primary drivers of low fertility in Thailand.

What is the difference between total fertility rate and crude birth rate?

Total fertility rate (TFR) estimates the average number of children a woman would have over her lifetime. Crude birth rate is the number of live births per 1,000 population in a year. TFR measures fertility levels; crude birth rate reflects population structure too.

Conclusion and next steps

Thailand’s total fertility rate has stabilized at very low levels around 1.2–1.3, with deaths exceeding births and aging accelerating. Long-term trends reflect structural forces: higher costs, delayed family formation, work intensity, and uneven childcare access. Regional variation persists, with some southern provinces above the national average, but not enough to change the national picture. Looking ahead, a combination of broad family supports, productivity growth, and well-managed migration will shape how Thailand adapts to an older, smaller population.

Your Nearby Location

Your Favorite

Post content

All posting is Free of charge and registration is Not required.