Thailand Food Guide: Regional Dishes, Street Food, Ingredients, and Classics

Thailand food is famous for balance, fragrance, and color. It brings together spicy, sour, sweet, salty, and bitter tastes in one harmonious experience, from market snacks to royal-inspired curries. This guide explains how Thai flavors work, where regional styles differ, which dishes to try first, and how to start cooking at home. It is written for travelers, students, and professionals who want a clear, practical overview.

- Core idea: balance of five tastes with fresh herbs and fermented seasonings.

- Meal style: shared plates with rice, adjustable heat, and table condiments.

- Regional diversity: Northern sticky rice culture, bold Isan salads, refined Central dishes, and fiery Southern curries.

- Street food: Bangkok hubs, safe-eating tips, and classic items to look for.

What defines Thailand food?

Thai cuisine begins with the idea of balance. Dishes are composed to deliver layers of taste rather than a single dominant note. A cook adjusts acidity, saltiness, sweetness, and heat using a small set of powerful tools, especially fish sauce, palm sugar, lime or tamarind, and fresh chilies.

Meals tend to be shared, and most combinations center on rice. The result is a cuisine that suits social eating and quick customization—diners can add dried chili flakes, sugar, vinegar, or fish sauce to fine-tune each bite. These habits are reflected across homes, markets, and restaurants, making Thai food both approachable and complex.

Core tastes and balance in Thai cuisine

Thai cooking seeks a dynamic equilibrium of five tastes: spicy, sour, sweet, salty, and bitter. Cooks tune this balance with fish sauce (salty-umami), palm sugar (gentle sweetness), lime or tamarind (bright or deep sour), and fresh herbs like lemongrass and kaffir lime leaves (aromatic lift). The concept of “yum” describes the hot-sour-salty-sweet harmony found in many salads and soups.

Everyday examples show this balance in action. Tom Yum soup layers chilies, lime juice, fish sauce, and herbs for a clear, zesty profile, while Som Tam (green papaya salad) combines palm sugar, lime, fish sauce, and chilies for a crunchy, refreshing bite. Chili heat is adjustable: vendors can reduce fresh chilies or use milder varieties without losing the overall balance, so the taste structure remains intact even at mild levels.

Meal structure and dining customs

Meals are communal, with several shared dishes served alongside rice. Diners usually use a spoon and fork, where the fork pushes food onto the spoon; chopsticks are common for noodle dishes only. Condiment trays—typically fish sauce with sliced chilies, dried chili flakes, sugar, and vinegar—let each person fine-tune heat, sourness, saltiness, and sweetness at the table.

Rice types reflect context. Jasmine rice is the default in most of Thailand, especially with soups and coconut curries, while sticky rice anchors meals in the North and Isan, pairing well with grilled meats, dips, and salads. Breakfast varies by region: in Bangkok you may find rice porridge and soy milk stalls, while in Isan, grilled chicken with sticky rice and early-morning Som Tam are common at roadside vendors. Street-side dining is casual, fast, and social, with peak times around early morning and evening commutes.

Regional cuisines of Thailand

Regional cooking in Thailand mirrors geography, migration, and trade. Northern cuisine favors herbal aromas and sticky rice, with influence from Myanmar and Yunnan. Isan, in the Northeast, leans into bold chili-lime flavors and grilled meats, reflecting Lao culinary traditions. Central Thailand blends refinement and balance, with Bangkok acting as a culinary crossroads for ideas and ingredients. In the South, abundant seafood and powerful curry pastes drive intensity and color.

Understanding these regional traits helps you decode menus and market stalls throughout the country. It also explains why the same dish name can taste different from Chiang Mai to Phuket. The summary below offers a quick orientation before the detailed sections.

| Region | Staple Rice | Signature Dishes | Flavor Traits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Northern (Lanna) | Sticky rice | Khao Soi, Sai Ua, Nam Prik Ong/Num | Aromatic, less sweet, herbal, mild heat |

| Northeastern (Isan) | Sticky rice | Som Tam, Larb, Gai Yang | Bold chili-lime, grilled, fermented notes |

| Central | Jasmine rice | Pad Thai, Tom Yum, Green Curry, Boat noodles | Refined balance, coconut-rich, polished presentation |

| Southern | Jasmine rice | Kua Kling, Gaeng Som, Gaeng Tai Pla | Very spicy, turmeric-forward, seafood-focused |

Northern Thailand (Lanna): signature dishes and flavors

Northern cuisine is aromatic and less sweet than the central style, with sticky rice as the staple. Signature dishes include Khao Soi, a curry noodle soup with a coconut milk base, and Sai Ua, a grilled herb sausage that highlights local spices and herbs. A family of spicy relishes known as nam prik—such as Nam Prik Ong (tomato-pork) and Nam Prik Num (green chili)—are commonly eaten with sticky rice, pork crackling, and fresh vegetables.

While Khao Soi uses coconut milk, the region as a whole is not coconut-rich. Herbal tones come from ingredients like dill and makhwaen pepper (a prickly ash with citrusy numbing notes), which reflect nearby Myanmar and Yunnan influences. Curries are often lighter and less sweet, and grilled or steamed preparations showcase the natural flavor of local produce and mushrooms.

Northeastern Thailand (Isan): grilled meats and bold salads

Isan food centers on sticky rice, grilled meats such as Gai Yang (chicken), and robust salads, especially Som Tam and Larb. The palette is boldly spicy and sour, driven by fresh chilies, lime juice, fish sauce, and pla ra, a potent fermented fish liquid that adds deep savory complexity to salads and dips.

Lao culinary influence is clear across Isan, shaping the reliance on sticky rice and herb-laden minced meat salads. Charcoal grilling, toasted rice powder, and handfuls of fresh herbs define texture and aroma. Pla ra intensity varies by vendor and town, so you can request “less pla ra” or choose a Thai-style Som Tam without it if you prefer a milder, cleaner finish.

Central Thailand: pad Thai, tom yum, and refined balance

Central cuisine emphasizes a refined balance of tastes and polished presentation. It is home to globally known dishes such as Pad Thai, Tom Yum, Green Curry, and richly flavored boat noodles. Coconut milk and palm sugar appear often, reflecting the fertile river plains and historic canal networks that have long supplied fresh produce and coconuts to the region.

Bangkok, as the capital and a major port city, is a melting pot that incorporates regional Thai, Chinese, and migrant influences. River market traditions shaped the noodle culture, including boat noodles served from canalside vendors. Today, this cosmopolitan mix fuels constant innovation while preserving classic combinations of aromatics, seafood, and meats.

Southern Thailand: very spicy curries and seafood

Southern food is known for high heat and saturated color, with abundant turmeric, fresh chilies, and robust curry pastes. Seafood is plentiful, and standout dishes include Kua Kling (dry-fried minced meat curry), Gaeng Som (sour turmeric chili curry), and Gaeng Tai Pla (intense curry seasoned with fermented fish viscera). The region’s Muslim communities contribute warm spices and slow-cooked stews.

Shrimp paste (kapi) plays a prominent role in many southern curry pastes, deepening aroma and umami. Southern Gaeng Som differs from central sour curries by using turmeric and a leaner, broth-like body rather than coconut milk; it tastes sharp and spicy rather than creamy. Expect assertive seasoning and plenty of fresh herbs to match the region’s seafood and tropical produce.

Iconic dishes you should know

Thailand’s most famous dishes convey both balance and variety. This selection spans stir-fries, soups, and curries that appear on menus worldwide and in local markets. Use it as a starting point for what to order and how to customize flavors to your preference.

Pad Thai: history and flavor profile

Pad Thai is a stir-fried rice noodle dish balanced by tamarind for tang, fish sauce for saltiness, and palm sugar for mellow sweetness. Typical add-ins include shrimp or tofu, egg, garlic chives, bean sprouts, and crushed peanuts. It rose to prominence in the mid-20th century and is now a global emblem of Thailand food.

To avoid overly sweet versions, you can request “less sugar” or ask the vendor to season more with tamarind. Regional or vendor-specific styles include Pad Thai wrapped in a thin omelet net and versions with dried shrimp or pickled radish for extra savoriness. Finish with lime and chili flakes to adjust brightness and heat.

Tom Yum Goong: hot-sour soup and UNESCO heritage

Tom Yum Goong is a hot-and-sour shrimp soup built on lemongrass, galangal, kaffir lime leaves, fish sauce, and lime juice. Two main styles exist: a clear, light broth; and a richer version with roasted chili paste, sometimes balanced with a splash of evaporated milk. Its profile and identity have been recognized widely for cultural significance.

Tom Yum differs from Tom Kha, which is coconut-enriched and milder in sourness. For quick reference, core aromatics in Tom Yum include: lemongrass, galangal, kaffir lime leaves, Thai chilies, and shallots. Ask for your preferred heat level, and consider adding straw mushrooms for extra texture.

Green curry: herbs and heat

Green curry paste features fresh green chilies, lemongrass, galangal, kaffir lime zest, garlic, and shallots pounded with shrimp paste. The curry is simmered with coconut milk and typically includes chicken or fish balls with Thai eggplant. The taste is herbaceous and sweet-hot, with intensity varying by cook and brand of chili.

Common vegetables include pea eggplant and bamboo shoots, which provide gentle bitterness and crunch. In some central versions, sweetness is more pronounced, whereas southern cooks may raise the chili heat and reduce sweetness. Adjust final seasoning with fish sauce, a touch of palm sugar, and torn kaffir lime leaves for aroma.

Som Tam: pounded green papaya salad

Som Tam combines shredded unripe papaya with lime, fish sauce, chilies, and palm sugar, pounded lightly in a mortar to release juices. Styles range from a clean Thai version to Lao/Isan versions seasoned with pla ra for deep, fermented savor. Add-ins like dried shrimp, peanuts, long beans, and salted crab change texture and flavor.

When ordering, specify spice level and whether you want pla ra. Pair Som Tam with sticky rice and Gai Yang (grilled chicken) for a classic Isan meal. If you prefer a milder profile, ask for fewer chilies and skip the salted crab while keeping lime and palm sugar for balance.

Massaman curry: warm spices and mellow heat

Massaman blends warm spices—cardamom, cinnamon, cloves, and nutmeg—with Thai aromatics like lemongrass and galangal. It is coconut-rich and gently sweet, commonly cooked with beef or chicken, potatoes, onions, and peanuts. Historical trade routes and Muslim culinary influence shaped its distinctive profile.

Halal-friendly options are common in Muslim-majority southern communities. The curry benefits from slow simmering to tenderize meat and meld spices; a low, steady heat keeps the coconut milk smooth. Season to finish with fish sauce and palm sugar, and add a squeeze of lime to brighten richness.

Pad Krapow: holy basil stir-fry and fried egg

Pad Krapow is a high-heat stir-fry of minced meat with holy basil, garlic, and chilies. Seasonings usually include fish sauce, light soy sauce, and a touch of sugar. It is served over hot rice and topped with a crispy fried egg so the runny yolk enriches the sauce.

Holy basil (krapow) has a peppery, clove-like aroma and is different from Thai sweet basil (horapha), which is sweeter and anise-like. When ordering at stalls, you can request the heat level—mild, medium, or “pet mak” (very spicy)—and specify your protein, such as chicken, pork, or tofu with mushrooms for a vegetarian variant.

Essential ingredients and flavors

Thai flavors come from a compact pantry of aromatics, chilies, fermented seasonings, and souring agents, supported by rice and coconut milk. Learning how each ingredient behaves will help you balance dishes and make smart substitutions when shopping abroad. The tips below focus on practical use, storage, and adjustments.

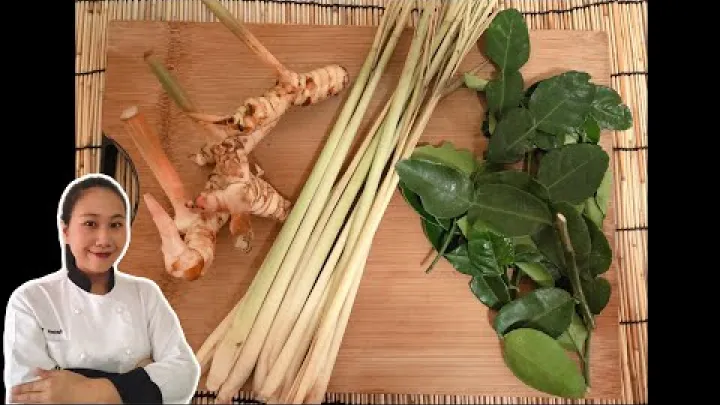

Aromatic herbs and roots (lemongrass, galangal, kaffir lime)

Lemongrass, galangal, and kaffir lime leaves form the backbone of many soups and curries. They deliver citrusy, peppery, and floral notes that define Thai aroma. These ingredients are usually bruised, sliced, or torn to infuse dishes and are not intended to be eaten whole due to their fibrous texture.

Before serving, remove large pieces to avoid tough bites. For buying and storage, choose firm, fragrant stalks of lemongrass; freeze excess galangal in coins; and keep kaffir lime leaves sealed and chilled or frozen. Freezing preserves aroma well, making it a good option when fresh supply is irregular.

Chilies and spices (bird’s eye chili, turmeric, pepper)

Bird’s eye chilies supply bright, sharp heat, while dried red chilies add color and deeper, toasty notes. Turmeric is central in the south, lending earthy bitterness and vibrant yellow color to curries like Gaeng Som. White pepper, more floral than black pepper, appears widely in stir-fries, soups, and marinades.

Control heat by adjusting chili quantity, removing seeds and membranes, or blending fresh with dried chilies for a rounder flavor. Fresh chilies taste greener and more aromatic; dried chilies taste smokier and slightly sweet after roasting. Start with less, then add more to reach the level you enjoy.

Fermented condiments and sweeteners (fish sauce, shrimp paste, palm sugar)

Fish sauce contributes salinity and umami, while shrimp paste deepens curry pastes and chili dips. Palm sugar balances acidity and heat with a gentle, caramel-like sweetness. Oyster sauce appears in many Chinese-influenced stir-fries for gloss and savory depth. In Isan, pla ra is a hallmark fermented fish seasoning for salads and soups.

Vegetarian alternatives include light soy sauce, mushroom-based dark soy, and seaweed or mushroom powder for umami. Season gradually to avoid over-salting; it is easier to add a few drops than to fix an over-seasoned dish. When substituting, expect a slightly different aroma and adjust with lime or sugar as needed.

Sour agents and staples (tamarind, coconut milk, jasmine and sticky rice)

Tamarind pulp and fresh lime are primary souring agents. Tamarind brings a deep, fruity sourness, while lime offers high, bright acidity; vinegar is less common in traditional dishes. Coconut milk adds body and richness, especially in central and southern curries.

Jasmine rice pairs best with soups, stir-fries, and coconut curries, while sticky rice is the daily staple in the north and Isan, ideal with grilled meats, dips, and salads. If a dish becomes too acidic, rebalance with a touch of palm sugar or a small splash of fish sauce. When substituting, lime plus brown sugar can mimic tamarind in quick recipes, though the flavor will be lighter.

Street food in Bangkok and beyond

Thai street food is fast, fresh, and focused. Vendors often specialize in one or two items, achieving consistency and speed. Bangkok concentrates many of the country’s street flavors in walkable neighborhoods and markets, while regional cities and towns offer local specialties at morning and evening stalls.

Where to find great street food in Bangkok

Bangkok has reliable areas where high turnover and variety make eating both safe and exciting. Yaowarat (Chinatown) is dense with seafood, noodles, and desserts, especially after sunset. Wang Lang Market, opposite the Grand Palace, excels at daytime snacks and quick lunches.

Victory Monument and Ratchawat are known for noodles and roast meats, with many stalls close to BTS or bus lines. New-style night markets like Jodd Fairs offer diverse vendors, seating, and convenient MRT access. Peak hours are 7–9 am for breakfast items and 6–10 pm for dinner; some stalls sell out early, so arrive near opening for signature dishes.

- Yaowarat (MRT Wat Mangkon): best at night for seafood and sweets.

- Wang Lang Market (near ferry from Tha Chang/Tha Phra Chan): strongest late morning to afternoon.

- Victory Monument (BTS Victory Monument): noodle boats and skewers all day.

- Ratchawat/Sriyan (north of Dusit): roasted duck, curries, and noodles.

- Jodd Fairs (MRT Rama 9): evening market with mixed vendors and seating.

Essential street foods to try

Start with a mix of grilled skewers, noodles, and sweets to sample the range. Moo Ping (grilled pork skewers) are sweet-salty and smoky, a Bangkok staple often eaten with sticky rice. Boat noodles deliver rich, spiced broths in small bowls, an old canal tradition tied to the Central region.

Som Tam and Pad Thai are common everywhere; the first is an Isan import with crunchy, bright flavors, and the second is a Central-style stir-fry with tangy-sweet notes. For texture adventures, try oyster omelet (crisp-chewy), satay with peanut sauce, diverse noodle soups, and Khanom Bueang (crispy crepes with sweet or savory fillings). Thai iced tea and fresh fruit juices—like lime, guava, and passionfruit—cool the heat and travel well.

- Moo Ping (Bangkok/Central): caramelized, tender; pair with sticky rice.

- Boat noodles (Central): intense broth, small bowls, quick slurps.

- Som Tam (Isan origin): crunchy, hot-sour; ask about pla ra.

- Pad Thai (Central): tamarind-sour, sweet-savory, with peanuts.

- Oyster omelet (Sino-Thai): crispy edges, chewy center, chili sauce.

- Satay (Southeast Asian): smoky skewers with cucumber relish.

- Khanom Bueang: wafer-thin crepes with coconut cream and fillings.

- Mango sticky rice (seasonal): ripe mango, salted coconut cream.

Practical tips for eating street food safely

Choose busy stalls with visible queues and quick turnover. Prefer dishes cooked to order, and watch for clean cutting boards and separate raw-cooked areas. Eat food hot, and opt for bottled or boiled drinks if you are sensitive to local water.

Communicate allergies clearly and ask vendors about peanuts and shellfish, which appear in many sauces and garnishes. If you are new to chili heat, start mild and add dried chili flakes or pickled chilies from the condiment set. Carry hand sanitizer, and avoid raw garnishes if you have a delicate stomach.

- Look for high turnover and hot holding temperatures.

- Ask about ingredients if allergic to nuts or shellfish.

- Start mild; add heat with condiments at the table.

- Use sanitizer or wash hands before eating.

How to start cooking Thailand food at home

Cooking Thai dishes at home is achievable with a small but focused pantry. Begin with one stir-fry, one soup, and one curry to learn core techniques. Quality ingredients and attention to balancing sour, sweet, salty, and spicy will get you close to the flavors you enjoyed in Thailand.

Pantry checklist and substitutions

Core pantry items include fish sauce, palm sugar, tamarind concentrate or pulp, coconut milk, jasmine rice, sticky rice, Thai chilies, lemongrass, galangal, and kaffir lime leaves. Garlic, shallots, white pepper, and shrimp paste support many recipes. Useful tools are a carbon steel wok, a mortar and pestle for pastes, and a rice cooker or steamer.

Substitutions help when ingredients are scarce. Lime plus a little brown sugar can stand in for tamarind, but the depth will be lighter. Ginger can replace galangal in a pinch, though it is sweeter and less peppery; add a touch of white pepper to compensate. Lemon zest can mimic kaffir lime aroma, but it is less floral. Check Asian markets for frozen lemongrass, galangal, and kaffir leaves—frozen options often outperform tired “fresh” herbs in regular supermarkets.

- Tamarind swap: lime juice + brown sugar (lighter, brighter result).

- Galangal swap: ginger (+ white pepper for bite).

- Kaffir lime swap: lemon zest (less floral; use more cautiously).

- Herbs: buy fresh in bulk and freeze extras for later use.

5-step method for a beginner Thai stir-fry

A simple method helps you cook consistent stir-fries at home. Prepare all components before heating the wok and keep portions small for high heat control. Use this sequence to build flavor and texture without overcooking.

- Prep and group: slice aromatics (garlic, chilies), protein, vegetables; mix sauces (fish/soy sauce, sugar). Keep everything within reach.

- Preheat: heat a wok on medium-high to high until it just smokes; add 1–2 tablespoons oil.

- Aromatics: flash-fry garlic and chilies for 10–15 seconds until fragrant.

- Protein and veg: sear protein 60–90 seconds; add vegetables, then sauces. Toss quickly to coat.

- Finish: deglaze with a splash of water or stock; toss in herbs; taste and adjust salt, sweet, and chili. Serve over hot jasmine rice.

Heat cues matter: if the wok is not hot enough, food steams and turns soggy; if too hot, garlic burns. Work in batches if needed, and keep total stir-fry time short to preserve crisp vegetables and tender protein.

Simple soup and curry starter ideas

Beginner-friendly choices include Tom Yum, Tom Kha Gai, and Green Curry using a quality store-bought paste. Bloom curry paste in a little oil to release aroma, then add aromatics and finally coconut milk and stock to build depth. Keep the simmer gentle to prevent coconut milk from splitting.

Good pairings include chicken with bamboo shoots or Thai eggplant for green curry; shrimp with straw mushrooms for Tom Yum; and tofu with mushrooms and baby corn for vegetarian versions. Before serving, taste and balance with fish sauce for salt, palm sugar for sweetness, and lime or tamarind for sourness. Adjust in small increments until the broth feels rounded.

- Green curry: chicken + bamboo shoots; tofu + eggplant.

- Tom Yum: shrimp + straw mushrooms; chicken + oyster mushrooms.

- Tom Kha: chicken + galangal coins; mixed mushrooms + baby corn.

Desserts and sweets

Thai desserts play with coconut richness, pandan fragrance, and palm sugar’s caramel notes. Many include a pinch of salt in the coconut cream to balance sweetness. Fruit-led desserts change with the season, while rice flour and tapioca give puddings and jellies a soft, bouncy texture.

Popular Thai desserts and key flavors

Well-known desserts include mango sticky rice, Tub Tim Krob (water chestnuts in coconut milk), Khanom Buang (crispy crepes), Khanom Chan (layered pandan jelly), and coconut ice cream served in cups or coconut shells. Core flavors are coconut cream, pandan, palm sugar, and tropical fruits.

Seasonality matters: mango sticky rice is best during peak mango season, when fruit is fragrant and ripe. Serving temperatures vary—mango sticky rice is room-warm with warm salted coconut cream, Tub Tim Krob is chilled, Khanom Chan is room temperature, and coconut ice cream is, of course, cold. Look for balance: a hint of salt in the coconut cream brings desserts to life.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the most popular foods in Thailand?

Pad Thai, Tom Yum Goong, Green Curry, Som Tam, Massaman curry, and Pad Krapow are widely popular. Regional favorites include Khao Soi in the North and Gai Yang with Som Tam in Isan. In Bangkok, boat noodles and Moo Ping are common street foods, all showing the cuisine’s balance of sour, sweet, salty, bitter, and spicy flavors.

Is Thai food always spicy, and how can I order milder dishes?

No. Heat varies by region and dish, and vendors can adjust chilies during cooking. Ask for “mild” or specify the number of chilies. Choose naturally milder dishes like Massaman curry or Tom Kha. Table condiments also let you add heat gradually.

What is Tom Yum Goong and how is it different from Tom Kha?

Tom Yum Goong is a hot-and-sour shrimp soup with lemongrass, kaffir lime leaves, galangal, fish sauce, and lime. Tom Kha is creamier and gentler, made with coconut milk and often chicken. Tom Yum is clearer and hotter; Tom Kha is richer with a softer sourness. Both use the same core aromatics.

What is the difference between Thai green curry and red curry?

Green curry uses fresh green chilies for a herb-forward heat and a brighter color. Red curry relies on dried red chilies for a deeper color and slightly smokier taste. Both are coconut-based and share similar aromatics, often including Thai eggplant and bamboo shoots.

Where can I find the best street food in Bangkok?

Reliable areas include Yaowarat (Chinatown), Wang Lang Market, Victory Monument, and Ratchawat. Night markets like Jodd Fairs offer diverse vendors with seating. Go in the evening for peak variety, follow queues for quality, and check hours since many stalls sell out early.

Is street food in Thailand safe to eat?

Yes, when you pick busy stalls with high turnover and food cooked to order. Look for clean prep areas and hot serving temperatures. Choose bottled or boiled drinks if sensitive, avoid raw items if unsure, and wash or sanitize hands before eating.

What ingredients are essential for cooking Thai food at home?

Fish sauce, palm sugar, tamarind, coconut milk, Thai chilies, lemongrass, galangal, and kaffir lime leaves are key. Stock garlic, shallots, shrimp paste, Thai basil, and jasmine rice. Sticky rice is important for Northern and Isan dishes. Frozen aromatics are fine if fresh is not available.

Does Thailand have an official national dish?

There is no legally designated national dish. Pad Thai and Tom Yum Goong are widely regarded as national icons due to their popularity and cultural identity. Both represent the balance and aromatic profile that define Thai cuisine.

Conclusion and next steps

Thai cuisine is a balance of five tastes, shaped by regional traditions and a culture of shared meals. Northern herbal dishes, bold Isan salads, refined Central classics, and fiery Southern curries show how geography and history influence flavor. Whether you explore Bangkok’s street food, order iconic dishes, or cook at home with a focused pantry, understanding key ingredients and simple techniques will help you achieve clear, satisfying results.

Your Nearby Location

Your Favorite

Post content

All posting is Free of charge and registration is Not required.