Bacolod History: Timeline, Key Figures, and Landmarks

Bacolod history spans coastal beginnings, a strategic inland move, and a rise as the capital of Negros Occidental. From parish foundations and haciendas to uprisings, wartime occupation, and postwar growth, the city has continually adapted. Sugar shaped its economy and architecture, while culture—from MassKara to cuisine—defines its identity today. This guide traces the timeline, key figures, and landmarks that explain how Bacolod became known worldwide as the City of Smiles.

Bacolod at a Glance

Bacolod at a glance offers a brief history of Bacolod City for travelers, students, and residents who want context fast. The city formed inland after coastal threats in the mid-18th century and has served as the provincial capital since the late Spanish period. Its role as a sugar hub, administrative center, and cultural hotspot makes it a natural gateway to Negros Island heritage.

Often called the City of Smiles, Bacolod connects historic neighborhoods and civic spaces with surrounding towns linked to sugar-era mansions and churches. These links explain how technology, capital, and people circulated in and out of Bacolod, shaping its social, political, and cultural life over centuries.

Quick facts

The inland town that became Bacolod was formed around 1755–1756, when residents left the coastal settlement of Magsungay after raids. Local heritage accounts widely accept this 1755–1756 range, reflecting a period when many Visayan communities moved to higher, defensible terrain.

In 1894, Bacolod became the capital of Negros Occidental, concentrating administration and commerce. The moniker City of Smiles grew with the MassKara Festival beginning in 1980. Geographically, Bacolod sits on Negros Island in Western Visayas, with Iloilo to the north across the Guimaras Strait, a longstanding corridor for trade and migration.

Why Bacolod matters in Negros history

Bacolod matters because it has long been the administrative heart of Negros Occidental. Decisions about taxation, infrastructure, education, and health flowed from here to the province. That centrality also made it a stage for political change, including the November 5, 1898 uprising that led to the short-lived Republic of Negros.

Economically, Bacolod sat at the center of the sugar industry’s plantation belt, influencing architecture, labor systems, and social hierarchies. Historic trade routes linked Bacolod with Iloilo’s port, enabling credit, steam-mill imports, and sugar exports to global markets. As a gateway city, Bacolod connects visitors to heritage landmarks, churches, museums, and civic plazas that preserve this layered past.

Origins: Magsungay and Relocation Inland (16th–18th centuries)

Bacolod’s origins begin on the coast at Magsungay, a settlement exposed to maritime threats common across the Visayas in the early colonial period. Security concerns pushed leaders and residents to rethink where and how to build their town. The move inland set the foundation for the community that would become Bacolod.

By the mid-18th century, residents sought higher ground known as “bakolod” or stone hill—an etymology still cited to explain the city’s name. This relocation helped define later development: a defensible site, a parish-centered town, and a civic core that would grow into a provincial capital.

Coastal settlement of Magsungay and Moro raids

Magsungay was the early coastal community associated with the area that later became Bacolod. Like many littoral settlements in the Visayas during the 16th to 18th centuries, it was vulnerable to periodic maritime raids. These incursions disrupted trade, agriculture, and everyday life, and they shaped local defensive strategies.

Local memory and chronicles describe how raids intensified risk for coastal residents, especially in the 1700s. Leaders weighed options that balanced access to fields and waterways against safety. Over time, the calculus favored relocating inland, away from the immediate reach of raiders, and toward terrain offering better visibility and natural protection.

1755 move to "bakolod" (stone hill) and first gobernadorcillo

Around 1755–1756, residents transferred from Magsungay to a site referred to as “bakolod”—literally a stony rise or hill. The move formalized a town on more defensible ground, where houses, a parish center, and civic space could be consolidated. This inland setting became the nucleus of the future Bacolod.

Administration under a gobernadorcillo provided local governance for taxation, justice, and defense. City and provincial records note early officeholders soon after the relocation, though precise names and tenures can vary across lists preserved in archives and church annals. The key takeaway is that structured leadership emerged alongside the new town plan, enabling coordinated growth and security.

Spanish Era: Parish, Administration, and Growth (18th–19th centuries)

During the Spanish era, parish and town government shaped Bacolod’s physical and civic life. The parish organized religious observances and social services; the municipal government kept order and coordinated public works. By the late 19th century, Bacolod had gained status as provincial capital, accelerating urban improvements.

This period set the architectural and institutional foundations seen today: a cathedral that traces its lineage to the late 1700s, plazas that structured public life, and administrative buildings that anchored the provincial bureaucracy. These elements framed the city’s transition into the sugar boom and political upheavals of the 1890s.

San Sebastian parish and early church

The Parish of San Sebastian was established in 1788, marking a key milestone in the history of Bacolod City. A resident priest arrived in 1802, stabilizing religious life and enabling more regular sacramental and community services. Over the 19th century, a succession of churches evolved into the present cathedral.

Coral stone quarried from nearby islands was used in its construction. Bell towers were completed a few years later and have undergone periodic restoration in the 20th and early 21st centuries, reflecting the cathedral’s sustained role in processions and public observances.

1894 designation as capital of Negros Occidental

In 1894, Bacolod was designated the capital of Negros Occidental. The decision consolidated government offices in a centrally located, increasingly accessible town. With capital status came expanded administrative functions and a growing concentration of merchants and professionals who supported provincial governance.

Infrastructure followed: roads, bridges, and plaza improvements organized movement and public gatherings. Administrators favored Bacolod for its strategic position along the coastal plain and its links by road and sea to the rest of Negros and nearby Iloilo. This choice laid the groundwork for the city’s pivotal role during the upheavals of 1898 and the transitions that followed.

Sugar Boom: Technology, Haciendas, and Architecture

The sugar boom transformed Bacolod and neighboring towns into an export-oriented agro-industrial region. Technology, capital, and shipping converged through nearby Iloilo, tying Negros mills to global markets. This surge influenced settlement patterns, labor systems, social hierarchies, and the city’s built environment.

Prosperity left visible marks: stone-and-wood houses, neoclassical civic halls, and Art Deco residences. Yet the boom also introduced vulnerabilities to world price swings and created labor challenges that later prompted reforms and civic activism.

Gaston, Loney, and export integration

Yves Leopold Germain Gaston is credited with pioneering modern sugar-making in Negros in the 1840s, particularly in the Silay–Talisay belt north of Bacolod. Around the 1850s, British vice-consul Nicholas Loney in Iloilo promoted steam-powered mills, credit facilities, and improved shipping, linking Negros planters to export markets.

By the mid- to late 19th century, mills in Talisay, Silay, and Manapla were integrating new equipment and capital. Bacolod, as the provincial hub, connected planters to bankers, shippers, and equipment suppliers. This network routed sugar to Iloilo and onward to international buyers, embedding the city in a global commodity chain.

Elite clans, haciendas, and social hierarchy

As sugar expanded, elite families such as the Lacson, Ledesma, Araneta, and Montelibano managed large haciendas. Political influence and patron–client ties shaped land tenure and local elections. Estates required skilled and seasonal labor, prompting migration within Negros and from nearby islands.

Tenant arrangements varied, from resident farm workers to seasonal sacadas who traveled during milling periods. Workers often came from Panay and Cebu, bringing languages, foodways, and religious devotions that enriched local culture. These dynamics forged a social hierarchy that influenced policy debates well into the 20th century.

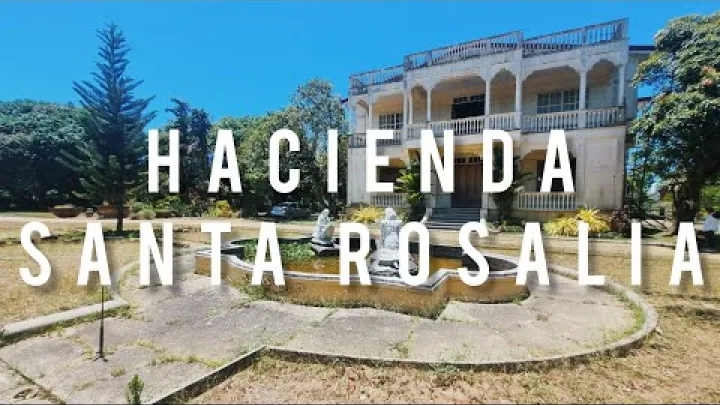

Built heritage: bahay na bato, neoclassical, Art Deco

Prosperity produced bahay na bato homes and later sugar-era mansions across the Bacolod–Silay–Talisay corridor. In Bacolod, government buildings of the early 20th century favored neoclassical designs, culminating in the Provincial Capitol complex. By the 1930s, downtown commercial strips adopted Art Deco facades, mirroring global styles.

Surviving examples anchor these styles in place and time: the Negros Occidental Provincial Capitol (neoclassical), the Art Deco “Daku Balay” or Generoso Villanueva House, and nearby landmarks such as Balay Negrense in Silay and The Ruins in Talisay. Together they visualize the arc from late Spanish prosperity to American-era civic planning.

1898 Uprising and the Republic of Negros

The events of 1898 reshaped political authority in Negros. As the Philippine Revolution spread, local leaders in Negros Occidental organized a coordinated uprising. Their success in Bacolod set the stage for a short-lived republic that navigated both revolutionary ideals and the realities of incoming American control.

Markers, commemorations, and public memory continue to honor this episode. In Bacolod, November 5—Cinco de Noviembre—remains a touchstone for civic pride and historical education.

Cinco de Noviembre: tactics and surrender

On November 5, 1898, forces under Aniceto Lacson and Juan Araneta staged an uprising that culminated in the surrender of Spanish authorities in Bacolod. Accounts emphasize psychological tactics, including improvised arms and coordinated positioning, that convinced the defenders they faced a larger, better-equipped force.

Local tradition identifies the surrender site near the center of town, with many references pointing to the convento of San Sebastian in Bacolod as the scene of capitulation. The outcome was achieved with minimal bloodshed and has entered regional lore as a defining moment of unity and strategic ingenuity.

Cantonal/Republic of Negros and governance

After the uprising, leaders proclaimed a Cantonal (Republic) of Negros with Bacolod as its capital. By late November 1898, provisional structures were in place, and early 1899 saw further organization as American forces arrived and established military authority over the archipelago.

Local officials coordinated with the new administration to maintain services and security. Autonomy was brief: by the early 1900s, the republic’s institutions were integrated into U.S. civil governance. Names and dates in decrees vary across documents, but the sequence runs from an initial cantonal proclamation in late November 1898 to reorganizations under American oversight in 1899–1901.

American Period: Education, Planning, and Urban Form

Under American rule, Bacolod’s institutions and urban planning took on new forms. Public schooling expanded quickly, English-language instruction spread, and civic buildings reflected standardized designs. Planners laid out street grids and civic centers that still structure movement and commerce today.

Trade ties with Iloilo remained strong, and improved roads and ports enhanced inter-island integration. These changes helped the city absorb population growth and set the stage for mid-20th-century development.

Public schooling and institutions

Public education grew rapidly in the early 1900s, with teacher training and English instruction shaping curricula. Secondary education expanded with institutions such as Negros Occidental High School (established 1902), which became an anchor for regional talent.

Religious and private colleges appeared as well, including La Consolacion College Bacolod (1919). Other schools that matured into universities—such as the University of St. La Salle (founded 1952) and the institution that became University of Negros Occidental–Recoletos—trace roots to this era’s educational momentum.

Street grids, civic buildings, and market integration

American-era planning introduced more regular street grids and a hierarchy of civic spaces. Markets, schools, and administrative buildings were placed to manage growth and services. The Provincial Capitol, designed in the neoclassical mode and commonly attributed to architect Juan M. Arellano, was completed in the 1930s and became a visual anchor.

Public markets and transport nodes connected farms to the city core, while improved port links across the Guimaras Strait tightened Bacolod–Iloilo trade. These systems integrated rural producers with urban consumers and exporters, shaping daily life and the city’s skyline.

World War II to Liberation (1942–1945)

World War II interrupted the city’s growth and brought new hardships. The Japanese occupation in 1942 imposed military control, rationing, and surveillance. Urban spaces and prominent homes were commandeered for headquarters, while resistance formed in the countryside and within the city’s networks.

By 1945, Allied forces returned and liberated Negros. The postwar transition was focused on restoring civil order, repairing infrastructure, and reviving the sugar economy that underpinned much of the region’s livelihood.

Japanese occupation and Daku Balay

Japanese forces entered Bacolod in 1942. The imposing Art Deco mansion known as Daku Balay—the Generoso Villanueva House, built in the late 1930s—was requisitioned as a headquarters during the occupation. Its size, vantage, and modern construction made it suitable for military command.

Civilians faced shortages, curfews, and coercion. At the same time, guerrilla groups organized across Negros, coordinating intelligence and sabotage. Daku Balay’s wartime role survives in local memory and scholarship, alongside acknowledgment of the Villanueva family’s place in the city’s architectural heritage.

Liberation, MacArthur visit, and recovery

Allied operations liberated Bacolod in 1945 as combined forces swept through Negros. With civil order reestablished, attention turned to clearing debris, reopening schools, and repairing mills and roads critical to the sugar-based economy.

Local accounts and newspapers from the period note visits by senior Allied leaders to Negros Occidental during liberation, often referencing General Douglas MacArthur in connection with inspection tours and morale-building engagements. For formal research, archival confirmation is advised. The broader trajectory is clear: Bacolod’s institutions resumed work and laid groundwork for postwar modernization.

Cityhood, Postwar Growth, and Diversification

Bacolod became a chartered city in 1938 under the Commonwealth, a status that framed postwar governance and expansion. The decades after liberation saw rapid urbanization, new neighborhoods, and a shift from a purely sugar economy to a more diverse mix of services, education, and tourism.

Contemporary civic complexes, universities, and business districts now complement historic plazas and markets. Together they present a city that honors its roots while pursuing new sectors.

1938 city status and postwar rebuilding

Bacolod gained city status through Commonwealth Act No. 326 signed on June 18, 1938, with the inauguration held on October 19, 1938. Historically, the city commemorated Charter Day each October to mark the inauguration’s anniversary. Subsequent national legislation recognized June 18 as the legal Charter Day, while local observances in October continue to carry cultural significance.

Postwar rebuilding added roads, bridges, and schools to accommodate growth. Neighborhoods expanded beyond the old core around the plaza and cathedral. Urban services professionalized, supporting public health, utilities, and transport as Bacolod assumed wider regional functions.

Government, education, and new sectors

The New Government Center symbolizes administrative modernization; it opened to the public in 2010 and consolidated city offices in a planned complex. This hub reflects contemporary expectations for access, parking, and service delivery.

Beyond sugar, services and business-process outsourcing have grown. Tourism tied to heritage, cuisine, and festivals rounds out a more diversified urban economy.

Culture and Identity: MassKara, Cuisine, and Museums

Bacolod’s identity is expressed through festivals, food, and museums that keep local history alive. The MassKara Festival projects resilience through art and performance. Signature dishes like chicken inasal and sugary treats reflect agricultural roots. Museums curate the past for future generations.

These cultural assets make Bacolod approachable for international visitors and students. They also provide local communities with enduring spaces for memory and creativity.

MassKara Festival and "City of Smiles"

Community leaders and artists responded by creating a street celebration of smiling masks, music, and dance, turning hardship into a statement of optimism.

Organization involved city officials, business groups, and cultural associations; the concept is often credited to local artists including Ely Santiago, whose mask designs influenced the festival’s iconography. Held each October, MassKara aligns with civic commemorations and has become a core reason why Bacolod is known as the City of Smiles.

Chicken inasal and regional food heritage

It is commonly paired with sinamak (spiced vinegar) and garlic rice, and it is widely served in the city’s Manokan Country and neighborhood grills.

Stalls and restaurants in nearby Talisay and Silay helped popularize styles of inasal, and eateries across Iloilo and other Visayan cities spread variations to broader audiences. Sugar-country snacks such as piaya—flatbread filled with muscovado—also reflect the region’s agricultural base and early 20th-century bakery traditions.

The Negros Museum and preservation

Located along Gatuslao Street in the former Provincial Agricultural Building near the Capitol Lagoon, it is accessible to students and visitors exploring the civic district.

Collections highlight the sugar industry, everyday objects, and contemporary art, while education programs support heritage awareness. Exhibits change over time, but the museum’s mission remains constant: to preserve, interpret, and share the many stories that define Negrense life.

Landmarks with Historical Significance

Bacolod’s historic landmarks and nearby sites allow visitors to read the city’s past in stone, wood, and open space. Mansions and churches recall the sugar era and parish beginnings, while plazas and government complexes show how planning shaped civic life. Together they form an outdoor archive.

These places serve as anchors for walking tours, classroom fieldwork, and personal reflection on the island’s history.

The Ruins: family story, WWII damage, and heritage value

Built in the early 1900s by Don Mariano Ledesma Lacson, The Ruins stands as a testament to the sugar era’s prosperity and family narratives. During World War II, it was deliberately burned to prevent its use by occupying forces, leaving the skeletal elegance admired today.

Although commonly associated with Bacolod, The Ruins is located in neighboring Talisay City, a short drive from the provincial capital. Open year-round, it has become a premier heritage landmark and a visual symbol of Negros’ ability to transform loss into shared memory.

San Sebastian Cathedral: religious continuity

The present coral-stone structure was substantially completed in the late 19th century and has remained the center of major processions and community observances.

Bell towers—completed in the years after the main church—frame the façade, and the complex has seen notable restorations in the 20th and 21st centuries to address age and earthquakes. For many residents, the cathedral embodies a continuous thread from Magsungay’s parish roots to the modern city.

Capitol Lagoon, Public Plaza, and civic spaces

The Provincial Capitol complex and lagoon are products of 1930s civic planning. The Capitol’s neoclassical design is widely attributed to Juan M. Arellano, with sculptural ensembles at the lagoon commonly credited to Italian sculptor Francesco Riccardo Monti. These works situate Bacolod within national currents of architecture and art.

Downtown, the Bacolod Public Plaza and its bandstand—commonly dated to the late 1920s—have hosted concerts, civic rites, and festival activities. Recent upgrades maintain shade, accessibility, and greenery. For visitors tracing Bacolod public plaza history, the site remains a living stage for the city’s cultural calendar.

Chronology: Key Dates and People

A concise chronology helps place Bacolod history in sequence. While individual sources may differ on exact years for some events, the following milestones are widely cited in local histories and civic commemorations. They show a steady evolution from coastal settlement to inland town, capital city, and cultural center.

The people behind these dates—planters, revolutionaries, architects, educators—shaped policy, economy, and culture. Understanding their roles provides context for landmarks and institutions that survive today.

Selected milestones (mid-16th century to present)

The timeline below lists key developments from the town’s relocation to recent diversification. It can support quick study for students and serve as a briefing for travelers planning heritage walks.

Where specific days vary across references, ranges reflect the consensus found in local records and commemorations.

- 1755–1756: Inland relocation from Magsungay to “bakolod” (stone hill).

- 1788: Establishment of San Sebastian parish; 1802 arrival of resident priest.

- Late 19th century: Present cathedral substantially completed (commonly 1882).

- 1894: Bacolod named capital of Negros Occidental.

- November 5, 1898: Uprising in Bacolod; surrender of Spanish authorities.

- Late Nov 1898–1901: Cantonal/Republic of Negros; integration under U.S. rule.

- 1930s: Provincial Capitol and Lagoon completed; civic planning consolidated.

- June 18 and Oct 19, 1938: City charter signed and inaugurated.

- 1942–1945: Occupation and liberation during World War II.

- 1980: MassKara Festival launched; “City of Smiles” identity grows.

- 2000s–present: Diversification, New Government Center (2010), education and BPO growth.

Key figures (Lacson, Araneta, Gaston, Loney, Jayme)

Aniceto Lacson (1848–1931, commonly recorded) led revolutionary forces during the November 5, 1898 events and later served in provincial leadership roles. Juan Araneta (1852–1924) co-led the uprising and helped organize the subsequent Cantonal/Republic of Negros.

Yves Leopold Germain Gaston (1803–1863) introduced modern sugar-making techniques to Negros in the 1840s, especially around Silay–Talisay. Nicholas Loney (1826–1869), British vice-consul in Iloilo, promoted steam mills, credit, and shipping that integrated Negros sugar into global markets. Antonio L. Jayme (1854–1937) served as a jurist and provincial leader whose legal and civic work influenced local governance during transition years.

Frequently Asked Questions

When was Bacolod founded and why did the settlement relocate inland?

Bacolod formed as an inland town in 1755–1756 after coastal Magsungay was devastated by raids. Residents moved several kilometers inland to higher, defensible ground, naming the new site “Bacolod” from “bakolod,” meaning “stone hill.”

What happened on November 5, 1898 in Bacolod?

Local revolutionaries captured Bacolod on November 5, 1898 using psychological tactics that led to a largely bloodless Spanish surrender. The victory enabled the establishment of the Cantonal (Republic) of Negros with Bacolod as its capital.

Why is Bacolod called the “City of Smiles”?

The name is linked to the MassKara Festival, created in the 1980s to uplift the city during economic and social crises. Smiling masks symbolize resilience, optimism, and a welcoming civic identity.

What is the historical significance of The Ruins in Bacolod?

The Ruins is the remains of a pre-WWII mansion built by a sugar baron, later burned during wartime to prevent use by occupying forces. It reflects the sugar era’s prosperity and has become an emblematic heritage landmark.

How did sugar shape the history of Bacolod City?

Sugar transformed Bacolod into a major export hub from the mid-19th century with modern milling, credit, and shipping. The industry built elite wealth, influenced politics and architecture, and exposed the city to global market cycles.

What role did San Sebastian Cathedral play in Bacolod’s early years?

San Sebastian parish anchored religious and civic life from 1788, with a resident priest from 1802 and early church construction in the 19th century. It preserved continuity from Magsungay and became a central community landmark.

Conclusion and next steps

Bacolod’s history begins on a vulnerable coast and moves inland to a defensible hill, where parish and town government took root. Sugar wealth and trade through Iloilo connected local haciendas to global markets, leaving a legacy of mansions and civic buildings. Political turning points—especially the 1898 uprising—demonstrated local agency during imperial transitions. The American period’s schools and planning, World War II’s trials, and postwar rebuilding shaped a modern provincial capital. Today, MassKara, chicken inasal, museums, and historic sites like San Sebastian Cathedral, the Provincial Capitol and Lagoon, and nearby The Ruins sustain a living heritage. Understanding these layers helps readers place Bacolod within Philippine and global histories and navigate the city with informed appreciation.

Your Nearby Location

Your Favorite

Post content

All posting is Free of charge and registration is Not required.

![Preview image for the video "[4K] Walking at Bacolod New Government Center & Afternoon at Kusinata". Preview image for the video "[4K] Walking at Bacolod New Government Center & Afternoon at Kusinata".](/sites/default/files/styles/media_720x405/public/oembed_thumbnails/2025-10/QwLkbhxQtDds6z77XfVdP94lJXitOhLC666pCaBB4kQ.jpg.webp?itok=dWSA-l7Z)

![Preview image for the video "Capitol Park & Lagoon Bacolod City [4K] Walking Tour". Preview image for the video "Capitol Park & Lagoon Bacolod City [4K] Walking Tour".](/sites/default/files/styles/media_720x405/public/oembed_thumbnails/2025-10/aUNaDOunO7K4MlpiJQKTwl1tSRd96tZxTPTG2v_rxOo.jpg.webp?itok=Zlc1x1Gd)